A new study of exceptionally long-lived Rottweilers revealed that keeping their testes for longer may help them age more gracefully, offering fresh clues for how hormones shape frailty and resilience in both dogs and humans.

In both dogs and humans, frailty associated with old age signals the body’s declining resilience to everyday stressors like illness or injury, and has a major impact on activities of daily living. Even small physical or health challenges can lead to big losses in function.

In a new study, researchers looked at exceptionally long-lived male Rottweilers to see how keeping their testes for different lengths of time influenced frailty and survival in old age, and how this might translate to older human men.

“The research applies a life course approach to determine whether early-life events, such as endocrine hormone disruption, can buffer against late-life challenges,” said study co-author Markus Schafer, PhD, a professor in the Department of Sociology at Baylor University. “The research results extend current interest in the role that gonadal hormones play in the development of frailty in older men to include a separate, yet complementary consideration – the significant influence gonad function exerts on the adverse consequences of frailty.”

Eighty-seven purebred male Rottweilers aged 13 years or older, all part of the Exceptional Aging in Rottweilers Study (EARS), were included. Each dog’s owner completed a structured veterinary interview covering 34 health variables, such as mobility, appetite, continence, strength, sensory decline, disease presence, and cognitive function. These were combined into a “Frailty Index” (FI) score. The researchers also measured the integrity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, which requires a short explanation.

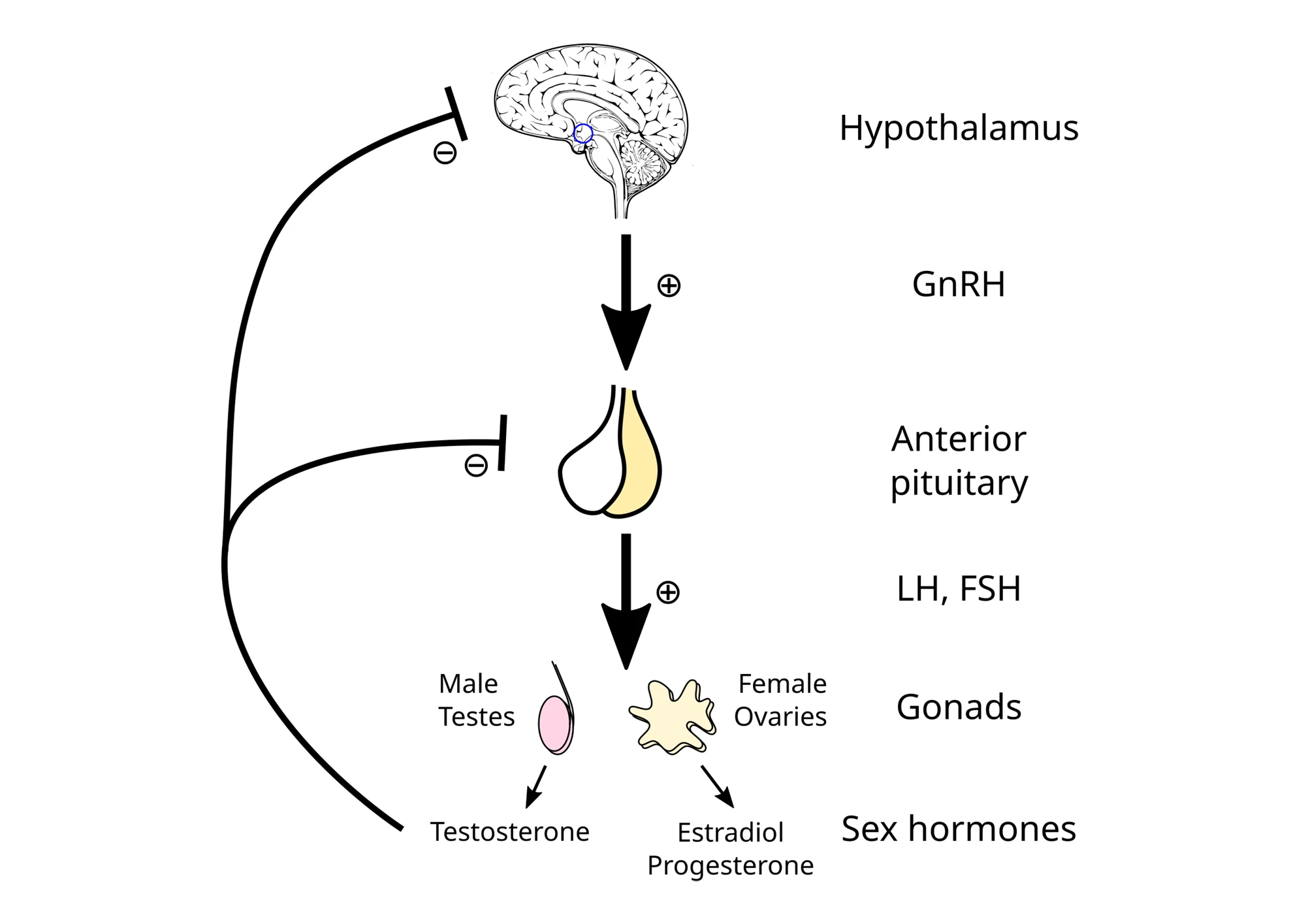

The HPG axis is the feedback loop between the brain and the gonads (testes or ovaries) that keeps sex hormones at healthy levels. The hypothalamus in the brain acts like a control center. It monitors hormone levels and, when it senses that sex hormones like testosterone or estrogen are low, it sends a signal called GnRH (gonadotropin-releasing hormone) to the pituitary gland, the messenger hub. When the pituitary gland receives this signal, it releases hormones into the bloodstream that tell the gonads to make sex hormones (luteinizing hormone, LH) and control sperm production and egg development (follicle-stimulating hormone, FSH). The gonads are the hormone factories. The testes make testosterone, and the ovaries make estrogen and progesterone. These hormones circulate through the body, influencing muscle mass, bone strength, mood, fertility, and even brain function. When hormone levels get high enough, the brain senses it and tells the hypothalamus to slow down GnRH production. This is the feedback loop that keeps the system balanced, like a thermostat maintaining a steady temperature.

Each dog was tracked from the time of frailty scoring until death. The researchers used Cox proportional hazards models, a standard survival analysis method, to see how frailty predicted mortality, overall and in groups with different durations of gonad exposure. To put it simply, and a bit crassly, “different durations of gonad exposure” means how long the dogs got to keep their balls (left “intact”) before they were neutered.

Frailty was found to increase with age. Older dogs had higher FI scores on average. However, early neutering was linked to worse outcomes. Dogs neutered before age two had a 16% increase in mortality risk for every small (0.01) rise in frailty score. Those kept intact for more than about 10 years showed no increased mortality with higher frailty. Essentially, frailty was less lethal for them.

Each additional year of being intact reduced frailty-related death risk by about 1%. This “buffering effect” wasn’t explained by other factors such as being overweight, being born earlier or later, or having been neutered for medical reasons. The pattern held even when only including cases with veterinary-record-confirmed neuter dates (to rule out owner recall bias). So, in short, the longer a dog’s hormonal system stayed intact, the better it could “handle” frailty when it eventually appeared.

“Our work provides the first description of the relationship between HPG axis integrity and the mortality risk associated with late-life frailty,” said the study’s lead and corresponding author, David Waters, PhD, DVM, Director of the Murphy Foundation’s Center for Exceptional Longevity Studies. “Male dogs with the shortest duration of testis exposure had a very high mortality risk associated with late-life frailty, whereas the mortality consequence of increasing frailty was erased in males with the longest gonad exposure.”

The authors note the limitations of the study, principally that it was observational and the neutering age wasn’t assigned, so causation can’t be proved. Additionally, because all dogs were male, the findings can’t automatically be applied to females. The study inferred HPG function from testis presence rather than testing testosterone or luteinizing hormone levels. All of the dogs were long-lived Rottweilers; results may differ by breed or environment. And, some information (body condition, neuter age) came from owners rather than direct veterinary measurements.

But how do these findings relate to humans? We’ve already seen how dogs can be used in comparative medical research into conditions such as cancer, in a way that benefits both them and us. The present study extends human research showing that low testosterone and disrupted HPG axis function are linked to frailty, suggesting dogs could be a useful comparative model for studying hormone-related aging resilience.

Understanding when hormonal disruption occurs may be crucial for both veterinary guidance and human geroscience, as early hormonal loss might set long-term biological “resilience limits.”

“Historically, dogs have played a pivotal role in endocrine hormone research, including the discoveries of insulin and the ability to shrink prostate cancers using androgen ablation,” said Waters. “Our work signals an important step toward better understanding frailty resilience, advancing the prospect that by avoiding HPG axis deterioration we might retain an internal hormonal environment that buffers the adverse impact of frailty.”

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source: Gerald P Murphy Cancer Foundation via EurekAlert!