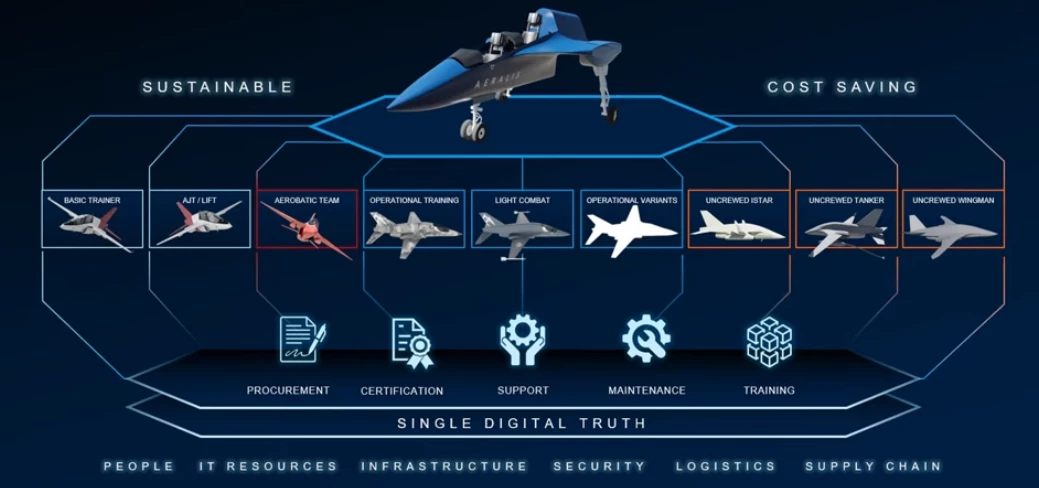

Bristol-based company Aeralis has unveiled a remarkable modular jet concept it says can handle an enormous range of different capabilities, from two-seat transonic advanced jet trainers to long-range ISR aircraft – delivering huge savings on maintenance.

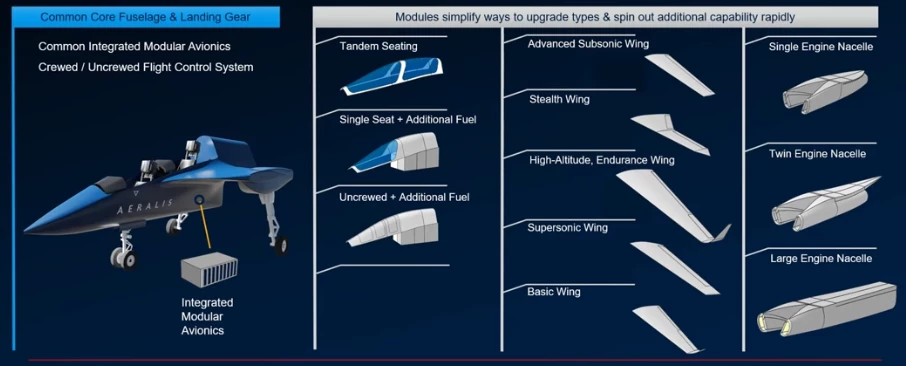

It's based on a "Common Core Fuselage" (CCF) with integrated modular avionics, into which a dizzying array of modular, interchangeable parts can be fitted. That starts at the cockpit, where you can slot in a two-seat tandem setup, a single-seat cockpit with extra fuel storage or electronic warfare equipment in the space behind it, or no seats at all, for a completely unmanned aerial system.

It continues back to the wings; the inner wing is common to all variants, but the outer wing could be a long, thin fella designed for high-lift, long-endurance flight more tailored toward ISR (intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance) missions, or a stealth wing, or a swept-back low-drag job designed for high transonic speeds, or an advanced subsonic wing designed for pulling high gs as an advanced jet trainer.

Even the engines will be interchangeable – swappable engine pods will be compatible with a range of different single engines, twin engines and large engines, using a series of adapter plates.

"We're not selling an aircraft, we're selling a whole system," says Aeralis Chief Airframe Engineer Peter Curtis, speaking to the Royal Aeronautical Society's Bedford Branch. "We're selling the ability to train pilots – which includes an aircraft, but also all the bits and pieces around it. With the actual flying product, what we're trying to do is maximize the commonality of structures, systems and parts, and add onto that some modularity, so that we can have a range of bespoke capabilities, but in a mostly common aircraft."

"I can't remember the actual number," he continues, "but the RAF has an astonishing number of different types of aircraft. Some of them they've only got three or four of. But they're these exquisite, boutique designs to fit a particular specification. But it's unaffordable to keep that whole range of different aircraft, and hold spare parts for very small fleets. What we're trying to do is to give you all that capability – the aircraft might not be quite as good, they might only be 90-95% good as the bespoke designs, but you'll save an absolute ton of money on it."

Aeralis has been running around setting up partnerships all over the place, with groups like Honeywell, Thales, Rolls-Royce, Siemens and others. It's received around US$13 million in investment from, "a Middle Eastern sovereign wealth fund," and has won multiple contracts with the UK Ministry of Defence.

It's also starting to sign MoUs with a bunch of conditional customers, and that's resulting in an interesting dance.

"The core product we're starting with is an advanced jet trainer – similar to Hawk and Alphajet and so on," says Curtis. "The trainer market is big, we've got to be talking to all of those [potential customers] trying to make sure we've got a product that's good enough for most, without tying it really closely to one requirement – because that's a sure-fire way to make sure it doesn't meet everyone's requirements."

It's a rather different pitch to what a lot of military customers tend to hear, but the cost savings make it compelling; you end up with aircraft that can evolve its capabilities over time, with interchangeable parts, and a vastly simplified maintenance operation, since so much of the architecture is shared across the entire fleet. Simulation and air tunnel testing is validating the idea.

"So we've got the CCF (common core fuselage)," says Curtis, "and we said, okay, the core product is going to be an 8G airplane. And we thought that probably, if you put a much bigger wing on it, for an ISTAR (intelligence, surveillance, target acquisition, and reconnaissance) airplane, or something with much longer endurance, it's probably going to be OK loads-wise. Well, we've done enough work now to say yep, that works. 8G for the AJT (Advanced Jet Trainer) and 5G for the ISR (Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance) – the load envelopes are almost identical. There's hardly any difference between them."

"Similarly," he continues, "if you're playing around with sweep, you're changing the center of pressure, so you're changing where the allowable center of gravity is. That looks like it's going to be manageable. We weren't sure about that to start with. And things like the landing gear, making sure they're far enough back that it doesn't tip back onto its tail, but far enough forward that you can actually lift the nose up for takeoff. All of that looks like it works."

Aeralis is looking to the future with other parts of the design, hoping, for example, to be able to swap in the necessary systems for taking off and landing on aircraft carriers.

"We've made the nose gear bay large enough for a carrier-capable nose gear," says Curtis. "And we've made the nose itself big enough to take a radar, for when we get to the variants that need a radar. Our training aircraft won't need radars, because we can do it synthetically. We can beam into the cockpit display what the radar would look like. That's done from the ground, saves an awful lot of money."

Interchangeability (ICY) is at the heart of a lot of design decisions.

"It's the sort of thing that in almost every aspect of life nowadays you'd expect," says Curtis. "That if you have a spare part and you go to put it on, it just fits, and things are interchangeable. Unfortunately in aerospace and aircraft structure, that's pretty uncommon. There's an awful lot of fettling and lining things up, and difficulty in joints. We have to make sure we have interchangeable, ICY joints. That we can unbolt and pull off an empennage and put on a new one, and everything lines up, and it just goes on."

So it's not just modular in terms of manufacturing; the jets can be reconfigured as necessary. That'll be huge for commercial operations handling contract-based training for various military groups; they can send the jets out to act as trainers for Typhoon pilots for a few years, then bring them back in, swap some modules over, and send them back out maybe a week or two later as trainers for F-35 Lightning pilots. And the operational flexibility for military commanders is obvious.

The interchangeability concept extends as far as the pilots themselves; Aeralis has designed its modular cockpits to accommodate nearly the entire range of American JPATS standard pilot sizes.

"It goes from basically gorillas down to really petite female frames," says Curtis, "and it's quite difficult to achieve a cockpit that can handle that whole range. The really big guy, you've got to make sure that when he ejects, you don't kneecap him with any of the wide area display screens. But then, the small-framed person can't have a problem reaching the display or controls. Getting a cockpit that can serve all those body types and still be safe for ejecting is pretty tricky. At the moment, our cockpit fits JPATS 1-6, and we're working hard to achieve number 7, which is an even smaller frame."

The company plans to build and test the aircraft first in the UK. And it's already broached the potentially thorny issue of certification, which will pose some interesting problems for regulators.

"Interestingly," says Curtis, "neither the MAA (Military Aviation Authority) or CAA (Civil Aviation Authority) feel comfortable and confident that they can do it on their own, but they're really up for doing it together. We've had a lot of discussions."

The company's timeline – which Curtis says is likely out of date and needs a bit of pushing back – would have first-variant prototypes commencing flight tests in mid-2025, and type certification and first customer deliveries in mid-2026, with a second variant starting flight testing around the same time. Even a year later would be pretty dang impressive from where we're sitting, for such a boundary-pushing design.

Check out Curtis's presentation to the Royal Aeronautical Society in the video below.

Source: Aeralis