Huge props to these two helicopter test pilots, who have white-knuckled it through one of the most harrowing experiences in rotorcraft flight – an unpowered autorotation emergency landing – allowing an autonomous system to take the controls.

Helicopters are known for being notoriously tricky aircraft to fly, requiring all four limbs acting in concert to manage the throttle, the collective control, the cyclic control and the pedals controlling the pitch of the tail rotor blades – check out our how to fly a helicopter piece from 2010 for a quick primer.

This full-body co-ordination exercise allows helicopters to be incredibly agile and precise in flight, provided the pilot is an absolute gun and got plenty of sleep last night – but a number of companies are working on fly-by-wire systems that hugely simplify the controls, or allow them to fly autonomously without pilot input.

These include Airbus, which has tested a single-joystick fly-by-wire system, and Sikorsky, which last year flew a Black Hawk in fully autonomous rescue and cargo mission demos without a pilot at the controls.

And then there's Skyryse, a California company that's been around since 2016, working on autonomous and fly-by-wire retrofit systems for a range of different aircraft, with the goal of reducing, and eventually eliminating, general aviation fatalities. The company demonstrated the first autonomous flight of its kind in 2019, using a Robinson R-44 upgraded with its Flight Stack technology.

Here's actor John Hamm using Skyryse tech to fly a chopper with a tablet a couple of years ago:

Early next year, the company says it'll reveal the first production helicopter to ship with a Skyryse simplified control system, and as part of that system, it's rolling out some world-first safety features, including fully automated autorotation for emergency landings.

Autorotation is a fairly terrifying concept – a last-ditch emergency maneuver that allows skilled pilots to bring a helicopter down to Earth softly and with a degree of control even in the case of total engine failure. It's effectively a series of techniques that let you convert the stored energy in your altitude, airspeed, and rotor speed – the same energy sources conspiring to kill you – into a chance of slowing your descent and making a controlled landing.

First, you need to immediately and counterintuitively drop the collective control to reduce drag on your top rotor, and make sure it keeps spinning. You've got a maximum of a couple of seconds to do this once the engine fails, or as FootFlyer points out, "once you've failed this maneuver the machine flies about as well as a 20 case Coke machine."

An automatic clutch will disengage the rotor from the engine, so there's at least one thing you don't need to worry about as you start to fall through the air. On the other hand, you'll need to get straight on the right pedal, because the loss of engine torque will cause the helicopter to start spinning to the left. If that's not addressed in short order, particularly in a hover, you're in for a particularly unpleasant death.

Ideally after this, you need to work the cyclic control to find the airspeed that'll keep the airframe aloft for the longest possible time – generally around 60 knots (69 mph/111 km/h), but it's particular to every model – then pick a spot for an unscheduled landing, and aim for it, remembering that every control input will affect the balance between airspeed, fall speed and rotor rpm.

If all this goes well, you attempt to glide to the landing spot, and somewhere between 40-150 ft (12-46 m) off the ground – again, depending on what you're flying, you pull back the cyclic to flare the aircraft into a rearward tilt, pulling to a complete halt 5-10 feet (1.5-3 m) off the ground if you're lucky, and then you use your remaining rotor speed to cushion your landing by yanking up on the collective stick as you drop those final few feet.

This wild series of events is not easy to execute. As AOPA puts it, "ironically, more helicopter accidents happen each year from practicing autorotations than from real-life engine failures." FootFlyer is a little more whimsical, noting that, "Even a perfectly executed autorotation only gives you a glide ratio slightly better than that of a brick."

If there's one thing scarier than performing an autorotation landing, it'd be sitting in the passenger seat while a student pilot does one. And if there's one thing scarier than that, it'd be sitting in the cabin during the world's first autonomous autorotation test.

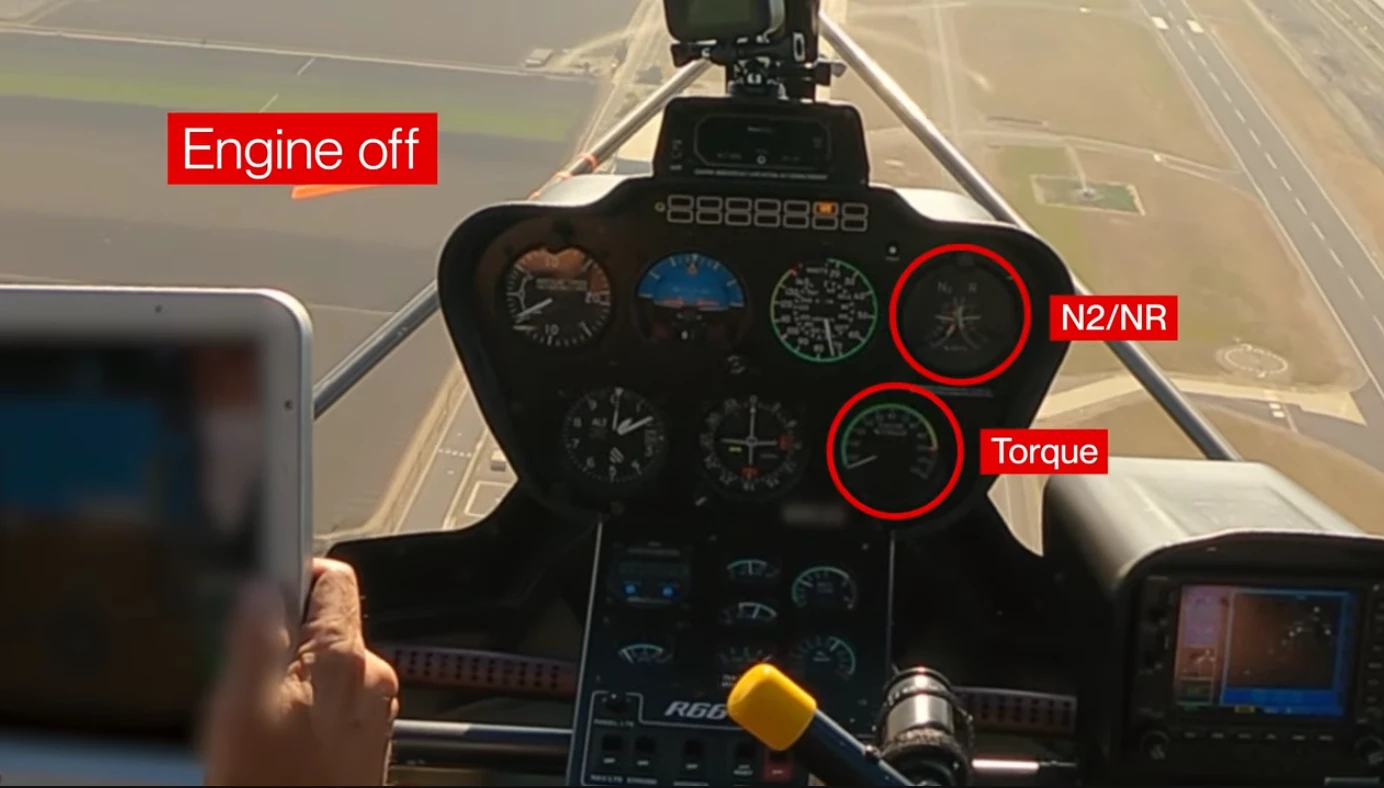

So full credit to test pilots Jason Trask and Eliot Seguin, who sacked up and tested Skyryse's automated autorotation system back in July, and stayed remarkably cool as the system brought their Robinson R66 down without incident.

The system is designed to recognize engine failure and instigate the entry into autorotation immediately, and probably quicker than a human pilot could do it – so in theory, it should maintain a higher main rotor RPM and give pilots more stored energy to work with. Once a glide is established, we presume it's up to the pilot to pick a landing spot and fly toward it.

Then, at the push of a button, the system takes over to complete the flare and the final landing. Check it out in the video below.

If Skyryse can take some of the guesswork and panic out of one of the most terrifying scenarios in aviation, it'll have a popular product on its hands. But we just can't get over the cojones of these two test pilots, experiencing an automatic autorotation for the first time ever. Helicopter pilots have a reputation for a steely nerve – by necessity – but these two sound cool as cucumbers in a situation that'd have most of us praying we remembered the brown underpants that day.

Source: SkyRyse