Sometimes you see a vintage plane that makes you scratch your head. Case in point is the US Air Force's X-29 of the 1980s that looks like a fighter with the wings stuck on backwards. Was this a daft mistake or a great leap forward? Let's have a look.

If you visit the National Museum of the Air Force in Dayton, Ohio or NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center in Edwards, California, you're likely to see one to two prototypes of one of the oddest aircraft to leave the drawing board.

The Grumman X-29 may resemble the product of some kid who put together a model airplane without reading the instructions, but there was some serious thinking behind building an aircraft with its wings sweeping dramatically forward instead of back.

In the 1930s, aeronautical engineers were fooling about with all manner of wings. When you don't fully understand things like that, you have an excuse. There were box wings, tube wings, cantilever wings, rotating wings, and wings that looked like Venetian blinds. If you could imagine a wing, someone was building it.

One idea was to sweep the wings forward instead of back. The idea was that such a wing would reverse the usual flow over it. Where a conventional back-swept wing has the air flowing from the root to the tips, a forward swept one flows from the tip to the roots. This results in reduced drag, greater maneuverability, and the ability to fly at a steeper angle of attack.

The concept was put into practice by Germany during the Second World War with the Junkers Ju 287 jet tactical bomber. It was later incorporated into the civilian Hansa Jet HFB-320 in the 1960s, but in both cases the wings were far from a success because of the tendency of the wings to be unstable due to excessive wing flexing.

In the 1970s, DARPA, the US Air Force, and NASA decided to take another look at the concept thanks to the development of new carbon composites that promised to make forward-swept wings more rigid without adding too much weight, as well as advances in computing technology that now had a chance of controlling an inherently unstable airframe that could get out of shape faster than a human pilot could be expected to correct for it.

The result was the X-29, which first took flight in 1984 and acted as a research testbed until 1992.

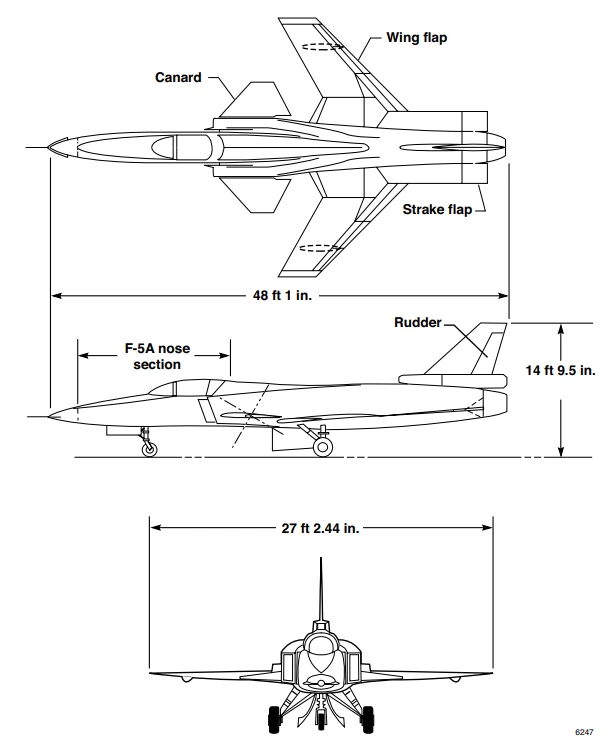

Two of the prototypes were built and from the outset they had a strange yet familiar profile. The odd wings were set far back on the fuselage, and instead of having tail stabilizers they had canards set forward of the wings. The familiarity sprang from the fact that the designers saved money by basing the design on an F-5 Freedom Fighter fuselage with the undercarriage from an F-15.

The X-29 had some very decent performance cred. Its General Electric F404-GE-400 engine produced a maximum of 16,000 pounds of thrust, giving it a top speed of Mach 1.5, an operational ceiling of 50,000 ft (15,000 m) and an endurance around one hour of flying time.

However, as expected, it was as unstable as all get-out.

This isn't always a bad thing; one pilot's instability is often another's idea of extreme agility, and in the era of the dogfight, the ability to turn on a dime was such an enormous advantage that some of the best aircraft were notoriously touchy at the stick. The Sopwith Camel, for example, took more enemy scalps than any other allied aircraft in WW1, thanks largely to its extreme handling capabilities.

But this instability made it notoriously difficult to fly – and indeed, nearly as many Camel pilots died during training as were lost in combat. The torque reaction from its large rotary engine made it so much faster turning right than left that some pilots preferred doing a Zoolander-style spin to a direct left turn. A stall would immediately result in a deadly tailspin. And a full tank of fuel moved the center of gravity back beyond the safe limit, resulting in a lot of crashes on takeoff.

Likewise, Germany's Fokker D7 was also highly touchy at the controls, particularly in prototype form; its thicker-than-usual wings resulted in some sketchy directional instability in a dive. When the Fokker company tried to sell the D7 to the German Luftwaffe during the First World War, they reportedly did their best to sell this as a feature, telling the German test pilots that the D7 was "ultra maneuverable."

Grumman's answer for the X-29's antisocial degree of aerodynamic instability was to install a state-of-the-art fly-by-wire system that corrected the craft's flight 40 times per second. Corrections were made by three computers on the basis of two computers outvoting the third.

And watching the thing in flight, the X29 certainly seems to have an extraordinary capability for lightning-fast turns and rolls – but it certainly needed that digital assistance. "If the aircraft didn't have that flight control system..." test pilot Rogers E. Smith tells Fighter Pilot Podcast in the video below, "that airplane at 250 knots would likely break in half. Because it's 0.12 seconds to double amplitude. It'd double its amplitude, that's how divergent it was, every 0.12 seconds."

In many ways the X-29 was a great success, providing US engineers with stacks of data that would be used in later aircraft designs. However, the wing's performance was not as great an advancement as had been hoped for.

In the end, the decision was made to base future fighter and bomber designs on new stealth technology, picking relative invisibility over hyper-maneuverability.

Still, it sure did spice up some toy plane and bedroom poster lineups in the 1980s!

Source: NASA