When is an empty tube not an empty tube? When it's a ramjet that uses rotating detonation technology to propel aircraft at hypersonic speeds. A case in point is Venus Aerospace's new Venus Detonation Ramjet 2000 lb Thrust Engine (VDR2).

One of the biggest hurdles that need to be cleared in making hypersonic flight practical is building engines that are capable of sustained thrust.

Currently, hypersonic systems are mainly based on glide bodies that are boosted to high speed and altitude by rockets and then accelerate to over Mach 5 by gliding back to lower altitudes. However, if you want to build airliners that can fly from San Francisco to Tokyo in one hour, you need something more like a jet engine.

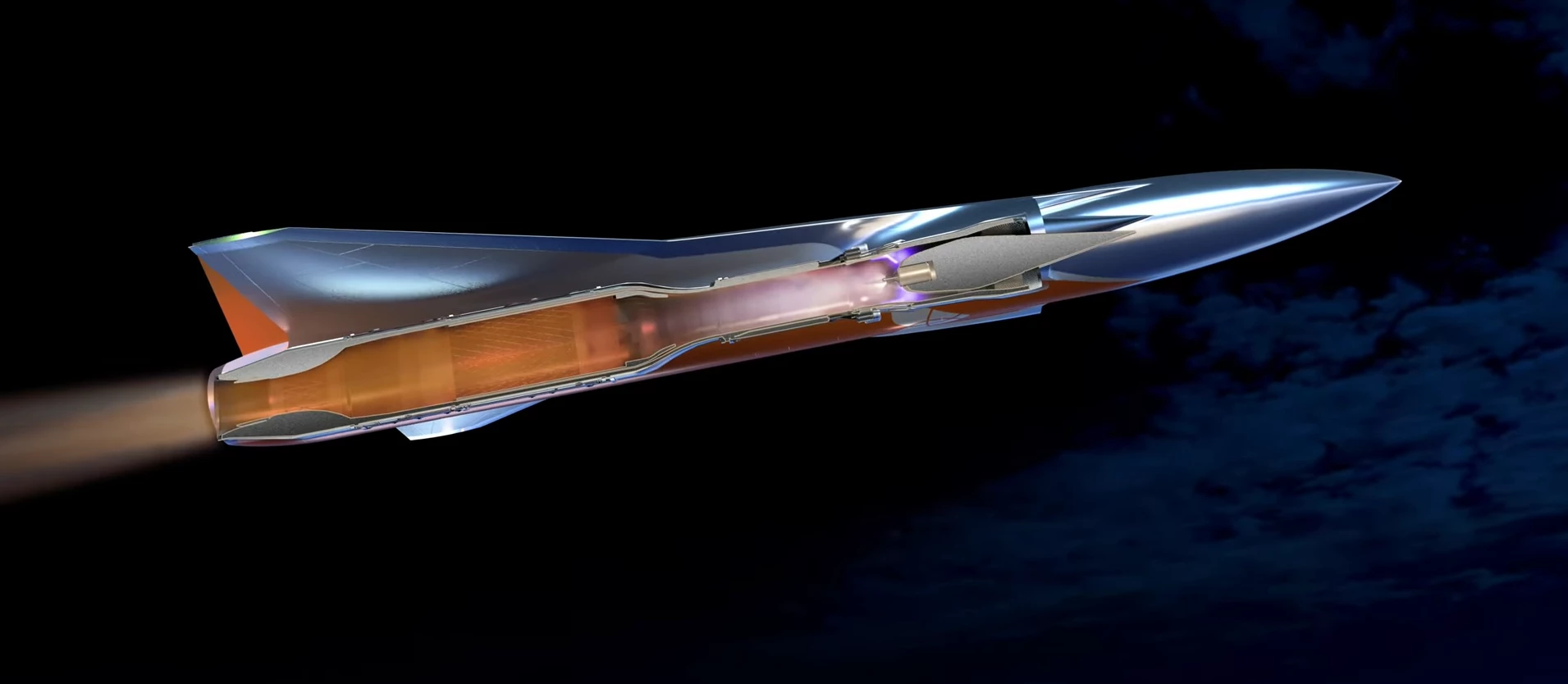

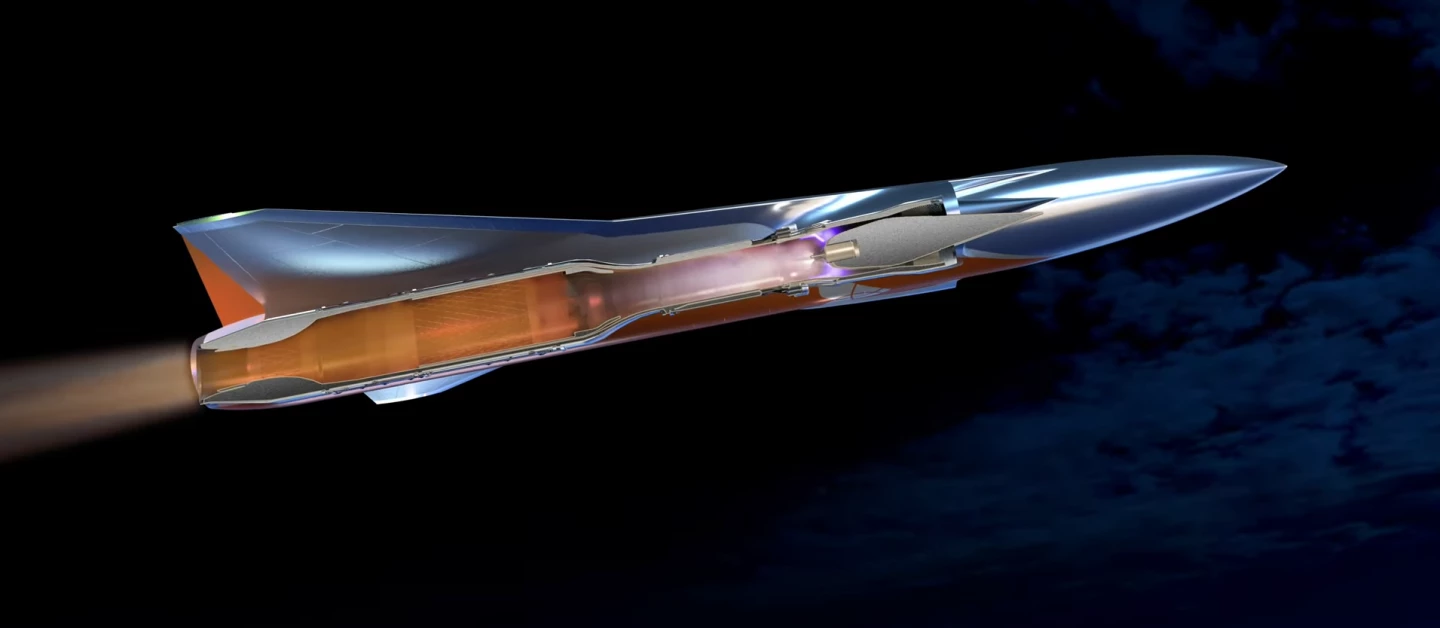

Unveiled at the recent Up.Summit in Bentonville, Arkansas the VDR2 looks ridiculously simple in a cutaway view because it's essentially an empty tube without moving parts. This is because it's mainly a ramjet, where the incoming air is compressed by the speed of the engine moving forward instead of by spinning turbine blades as in a conventional jet engine.

The reason a ramjet is attractive for hypersonic flight is that it can tolerate much higher temperatures than a conventional engine thanks to being mechanically simple and having no moving parts. This is important because air coming into an engine at hypersonic speeds can make the interior reach 2,130 °C (3,860 °F) and would quickly melt turbine blades or similar components.

However, there is room for improvement. The VDR2 takes things a step further by incorporating a Rotating Detonation Rocket Engine (RDRE), which overcomes the limitations of a rocket or jet engine by using another novel principle – again, with no moving parts. The RDRE part of the VDR2 consists of two coaxial cylinders with a gap between them. A fuel/oxidizer mixture is squirted into the gap and ignited. The next step is a bit tricky, but if the detonation is configured properly, this generates a closely coupled reaction and shock wave that speeds around inside the gap at supersonic velocity that generates more heat and pressure.

The result is a low-drag engine being developed in partnership with Velontra and builds on a previous Venus Aerospace project. It has the high thrust and efficiency needed to power an aircraft to speeds of up to Mach 6 and an altitude of 170,000 ft (52,000 m) and is 15% more efficient than conventional engines, if Venus Aerospace meets its current design goals.

"This engine makes the hypersonic economy a reality," said Venus Aerspace CTO Andrew Duggleby. "We are excited to partner with Velontra to achieve this revolution in high speed flight, given their expertise in high-speed air combustion."

The VDR2 is expected to make its first test flight in a test drone next year.

Source: Venus Aerospace