Mysteries surrounding an ancient, long-necked reptile that lived 242 million years ago have been resolved after almost 170 years by an international team led by the Chicago Field Museum of Natural History. First described in 1852, Tanystropheus is so difficult to understand from its fossils that at one time scientists weren't even sure if it swam in the sea or flew in the sky.

In many ways, paleontologists are the detectives of the scientific world. Much like the stereotypical crime detective who can tell a lot about a crime scene based on seemingly trivial clues, paleontologists look at the bones of long-dead animals as a way to deduce facts about their physiology and habits.

In most cases, this is a very simple and productive tool that allows scientists to make major discoveries from fragments of bone and teeth. These can not only tell something general like if an animal was a carnivore or a herbivore but can even identify a particular species and its relationship to others from a single tooth fragment.

However, such analysis isn't cut and dried in the case of outlier creatures that show peculiar characteristics that defy explanation. In the case of Tanystropheus with its very long neck in relation to its body, scientists weren't sure if it was a sea creature, a land creature, or a flying reptile similar to a pterodactyl since its discovery in 1852 in Switzerland.

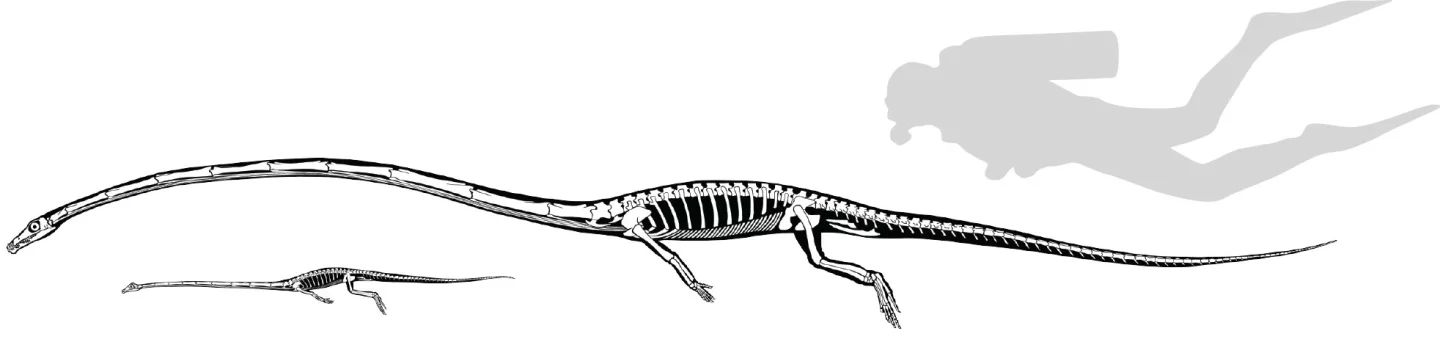

Part of the problem was a series of elongated bones that could be mistaken for wing parts but turned out to be segments of a 10-foot-long (3-m) neck that made up half the length of the 20-ft (6-m) crocodile-like reptile, or three times the length of its torso.

According to the Chicago team, not only was it unclear whether Tanystropheus was a land or sea animal, there was even confusion about smaller reptiles associated with it – were they juveniles or a separate species?

The breakthrough came when the researchers made computerized tomography (CT) scans of the crushed fossil skulls and used them to digitally reconstruct the skulls in 3D as they would have looked in life. They found that the Tanystropheus skull had its nostrils on top of the snout like a crocodile, indicating that it lived in the water, lying in wait for prey to swim by, which it would capture with its long, curved teeth. However, like sea turtles and other marine reptiles, it may have come ashore to lay its eggs.

As for the small, supposed juvenile reptiles, the team examined the growth rings in their bones, which showed that these were adults rather than juveniles. So, there are now two distinct species. The smaller is named Tanystropheus longobardicus and the larger Tanystropheus hydroides. These coexisted in the coastal waters of the ancient sea of Tethys by hunting different prey.

"These two closely related species had evolved to use different food sources in the same environment," says Stephan Spiekman, a researcher at the University of Zurich. "The small species likely fed on small shelled animals, like shrimp, in contrast to the fish and squid the large species ate. This is really remarkable because we expected the bizarre neck to be specialized for a single task, like the neck of a giraffe. But actually, it allowed for several lifestyles. This completely changes the way we look at this animal."

The findings were published in Current Biology.