After only 162 years, the first complete dinosaur skeleton to be recovered has finally been properly reconstructed and studied. Found on the shore beneath Black Ven at Charmouth in west Dorset, the 193-million-year-old fossilized remains of a Scelidosaurus, spent over a century and a half stored at the Natural History Museum in London before being fully described and analyzed by Dr. David Norman of the University of Cambridge's Department of Earth Sciences.

Dinosaurs have become so much a part of our modern culture that it's surprising to many people that their discovery didn't happen until around 1824. In fact, the word "dinosaur" was only coined by Richard Owen in 1842. Before this time, dinosaur fossils had been uncovered from time to time, but these were attributed to being the remains of dragons and giants.

When the first dinosaurs were identified, it was from fragments rather than complete skeletons, which resulted in some reconstructions that look very odd to modern eyes. The first full-size reconstructions were made out of concrete and went on display at London's Crystal Palace in 1854. Rather than the lithe, majestic animals depicted in the 1991 feature Jurassic Park, these were depicted as low-slung, heavy creatures built along the lines of an iguana or a monitor lizard.

As for Scelidosaurus, its first remains were uncovered in a quarry in 1858 by James Harrison and sent to Owens at the British Museum. Because these were mixed in with bones from other animals, Owen asked Harrison to collect more specimens. In about a year, Harrison had found the first-ever complete skeleton of a single dinosaur.

According to the University of Cambridge, the result of this discovery was that Owen published two short, incomplete papers, but the dinosaur was never fully described and the remains ended up in storage at the Natural History Museum – the fate of a surprising number of scientific discoveries.

Then, around 2017, Norman took a fresh look at Scelidosaurus and not only produced a proper reconstruction but also where it sits in the evolutionary tree of the dinosaurs, which it is helping to tweak a bit.

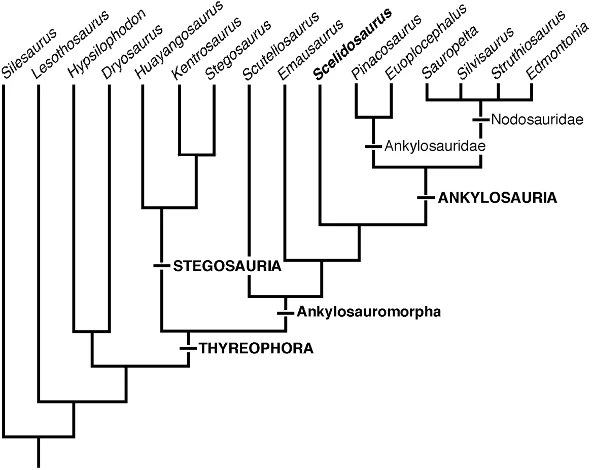

Until recently, scientists thought that dinosaurs fell into two groups: the saurischians (lizard-hipped) and the ornithischians (bird-hipped), but Norman and his students have called that into question, stating that bird-hipped dinosaurs and lizard-hipped dinosaurs have a common ancestor, with Scelidosaurus sitting close to the origin of the ornithischians. In addition, Scelidosaurus has displayed some firsts.

"Nobody knew that the skull had horns on its back edge," says Norman. "It also had several bones that have never before been recognized in any other dinosaur. It is also clear from the rough texturing of the skull bones that it was, in life, covered by hardened horny scutes – a little bit like the scutes plastered over the surface of the skulls of living turtles."

Scelidosaurus also had an array of stud-like bony spikes and plates to protect its skin, which made scientists conclude that it's an ancestor of the stegosaurs, with their spine plates and spiked tail, and the ankylosaurs, with their armored hide and mace-like tail. Now, the complete skeleton shows that it is a relative of only the ankylosaurs.

"It is unfortunate that such an important dinosaur, discovered at such a critical time in the early study of dinosaurs, was never properly described," says Norman. "It has now – at last! – been described in detail and provides many new and unexpected insights concerning the biology of early dinosaurs and their underlying relationships. It seems a shame that the work was not done earlier but, as they say, better late than never."

The research was published in four papers in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London (1), (2), (3), (4).

Source: University of Cambridge