Described as "the missing evolutionary link in the fish to tetrapod transition," a fascinating Canadian fossil reveals an ancient fish species with arm, hand and finger bones similar to our own, wrapped in fins.

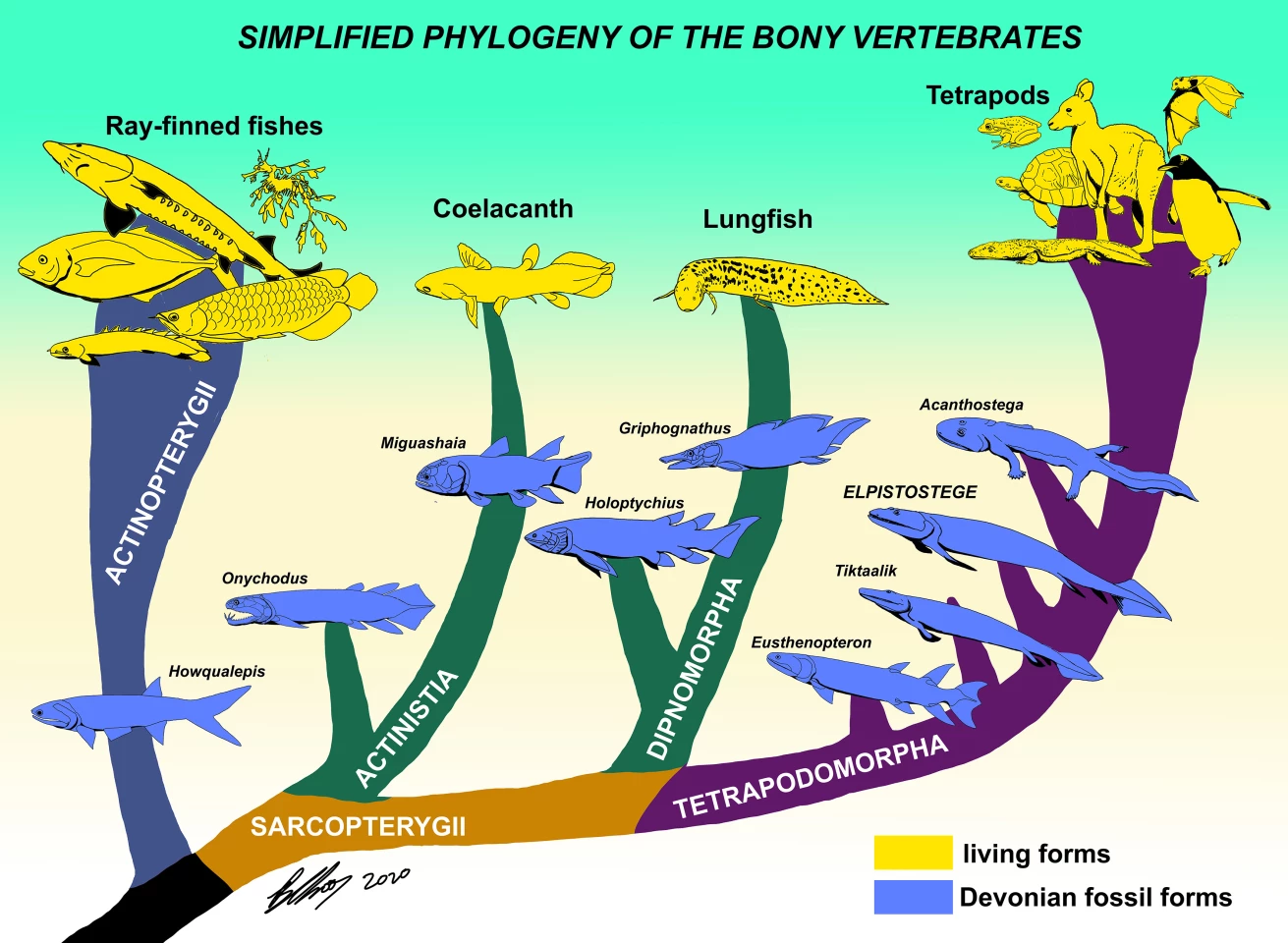

Found some 10 years ago in the Miguasha National Park in Canada's Southeast, the 157-cm (61.8-in) specimen dates back to somewhere between 393 and 359 million years ago, a period called the Late Devonian age in which a certain family of fish were beginning to experiment with coming out of the water. These adventurous little fellas eventually evolved into the entire family of tetrapods, or four-legged vertebrates, a family that includes dinosaurs, reptiles, birds, amphibians, whales, dolphins, seals, sea turtles and mammals – including humans. Quite a legacy.

Moving out of the water was one of the most profound and mysterious evolutionary leaps in history, and besides needing to develop a way to breathe dry oxygen, these fish found it difficult to support their weight and move on dry land. That is, until some of them started exhibiting rudimentary arms.

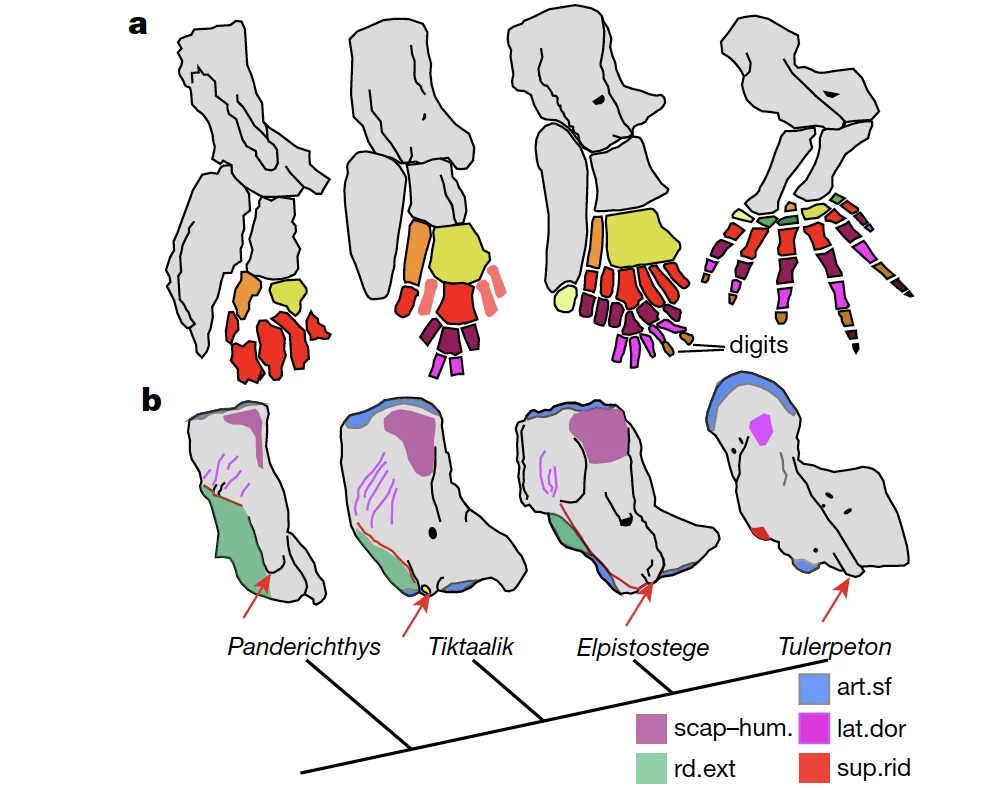

The humerus, radius, ulna, carpus bones of the wrist and the phalanges organized into digits all appeared around this time, and fish lucky enough to receive these mutations would have found it much easier to get around without the buoyant assistance of the water.

That's what we're looking at here with this new Elpistostege fossil. “This is the first time that we have unequivocally discovered fingers locked in a fin with fin-rays in any known fish," said John Long, Strategic Professor in Palaeontology at Flinders University. "The articulating digits in the fin are like the finger bones found in the hands of most animals. This finding pushes back the origin of digits in vertebrates to the fish level, and tells us that the patterning for the vertebrate hand was first developed deep in evolution, just before fishes left the water.”

The Late Devonian age is particularly fascinating to evolutionary biologists, because this is where a lot of the systems in the human body first appeared. In the last decade, finds from this era have told scientists a lot about the early development of the breathing, hearing and eating systems we still use today in a much more refined form.

Elpistostege fills a significant gap in our family tree, as the most evolutionarily advanced "fish" we know of that can still be classed as a fish and not a tetrapod. Equipped with a big set of fangs, it was the largest predator in its area. "Elpistostege is not necessarily our ancestor," said study co-author Richard Cloutier from Universite du Quebec a Rimouski. "But it is closest we can get to a true ‘transitional fossil’, an intermediate between fishes and tetrapods.”

The research was published in the Journal Nature.

Check out a short animation of what Elpistostege may have looked like in motion, in and out of the water, below. There are photos of the fossil itself in the gallery.

Source: Flinders University