Fruit flies differ from us in a great many ways, including the fact that they can't move their eyes relative to the rest of their head. That's not a problem, however, as new research shows that they move their retinas within their unmoving eyes instead.

Fruit flies actually aren't the first animals known to utilize the retina-moving strategy. Spiders had already been observed doing so, which led The Rockefeller University's Lisa Fenk and Assoc. Prof. Gaby Maimon to wonder about the flies. Dr. Fenk was a postdoctoral scholar in Maimon's lab at the time, and is now a group leader at Germany's Max Planck Institute for Biological Intelligence.

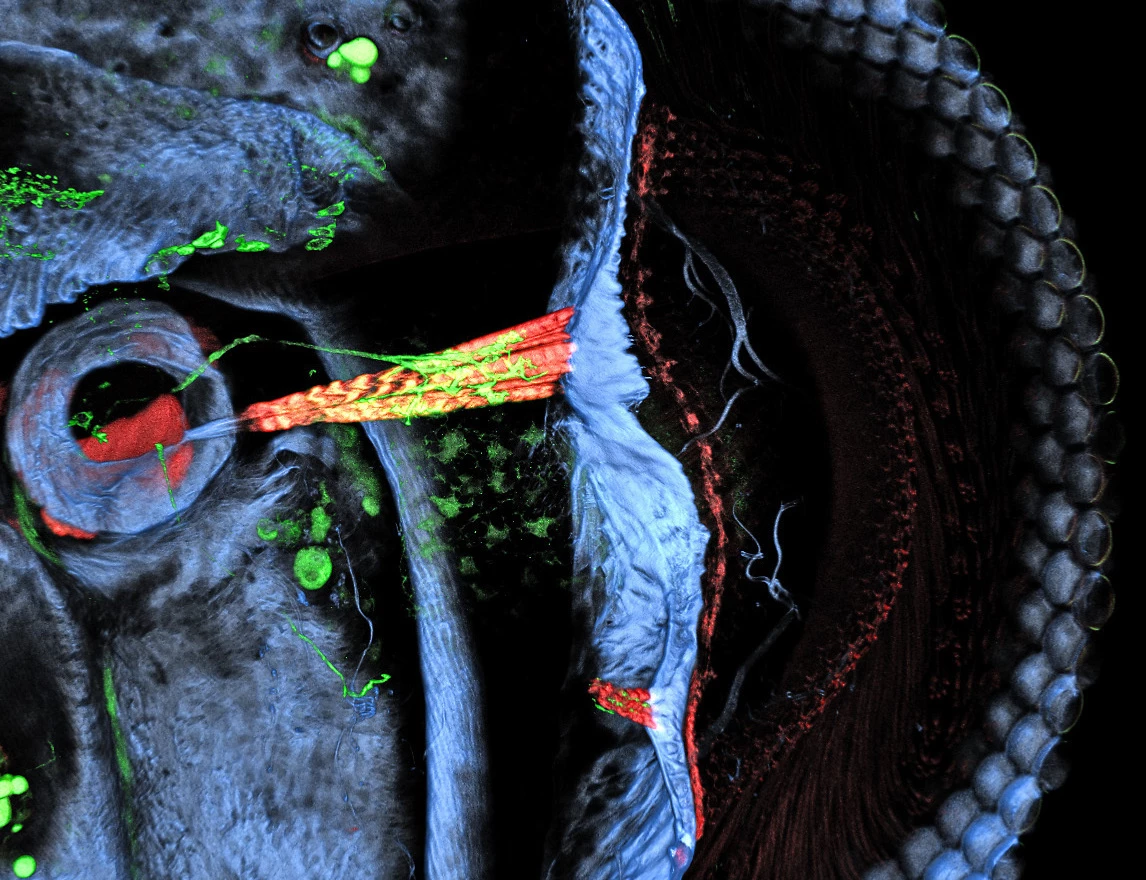

Utilizing a fluorescent molecule that binds to muscle fibers, the scientists initially discovered that fruit flies do indeed have two muscles attached to each of their retinas – these muscles allow the retina to move both back and forth, and up and down. When flies were subsequently placed in front of a panoramic LED screen with their heads immobilized, it was found that they moved their retinas to follow moving patterns which were displayed on the screen.

Eye movements aren't just used to follow the action, however. When we're viewing stationary objects, our eyes still make tiny involuntary movements known as microsaccades. These keep our visual neurons from adapting to the visual stimuli, so our eyes keep seeing what we're looking at. Otherwise, our perceived image of the object would start to fade, until we made a conscious effort to move our eyes.

When the flies were presented with stationary scenes, their retinas likewise made tiny microsaccade-like movements. It is believed that along with the purpose that microsaccades serve in humans and other animals, the flies' retinal movements may also help improve the resolution of their vision – whereas we have approximately 150 million photoreceptor neurons in each eye, fruit flies have only about 6,000.

Additionally, the insects' movable retinas might allow them to do something that we can't.

When flies were held on a treadmill-like apparatus with small gaps within the walking surface, their retinas moved toward one another in a cross-eyed fashion at the moment of crossing the gaps – which they were easily able to do. When the same test was performed on flies that were engineered to have slower-moving retinas, the insects had more difficulty crossing the gaps. This suggests that by sweeping their retinas together, fruit flies are able to judge the distance of gaps they're approaching.

"It is super interesting that fruit flies move their retinas because it suggests there could be a whole other set of features yet to be discovered that the visual system uses to help gather and process information," said Fenk. The scientists believe that their findings may even lead to a better understanding of human cognitive disorders in which eye movements are impaired, such as autism and schizophrenia.

A paper on the research was recently published in the journal Nature.

Source: The Rockefeller University