For more than a century, biologists assumed that the bony plates embedded in the skin of lizards – like natural chain mail – were an ancient feature that some lineages inherited and others later lost. But new evidence suggests this is completely wrong.

In a new study from Museums Victoria Research Institute (MVRI), researchers have found that instead, most lizard bony plates – osteoderms – evolved multiple times independently, long after the major lizard groups had already split apart. Essentially, many lizards didn’t inherit armor from a common ancestor but evolved it again completely from scratch – and even refined it – sometimes tens of millions of years after they'd lost it.

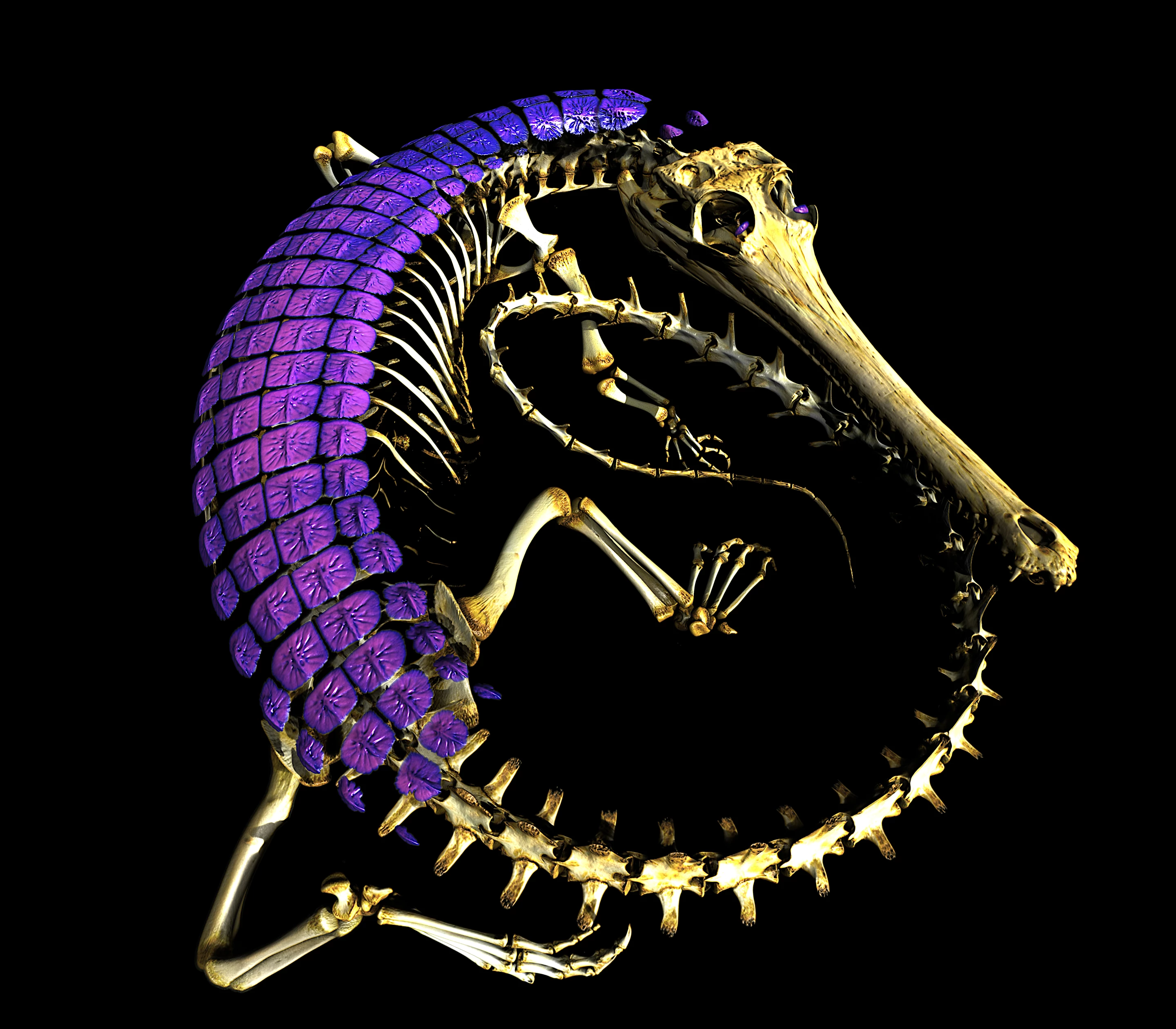

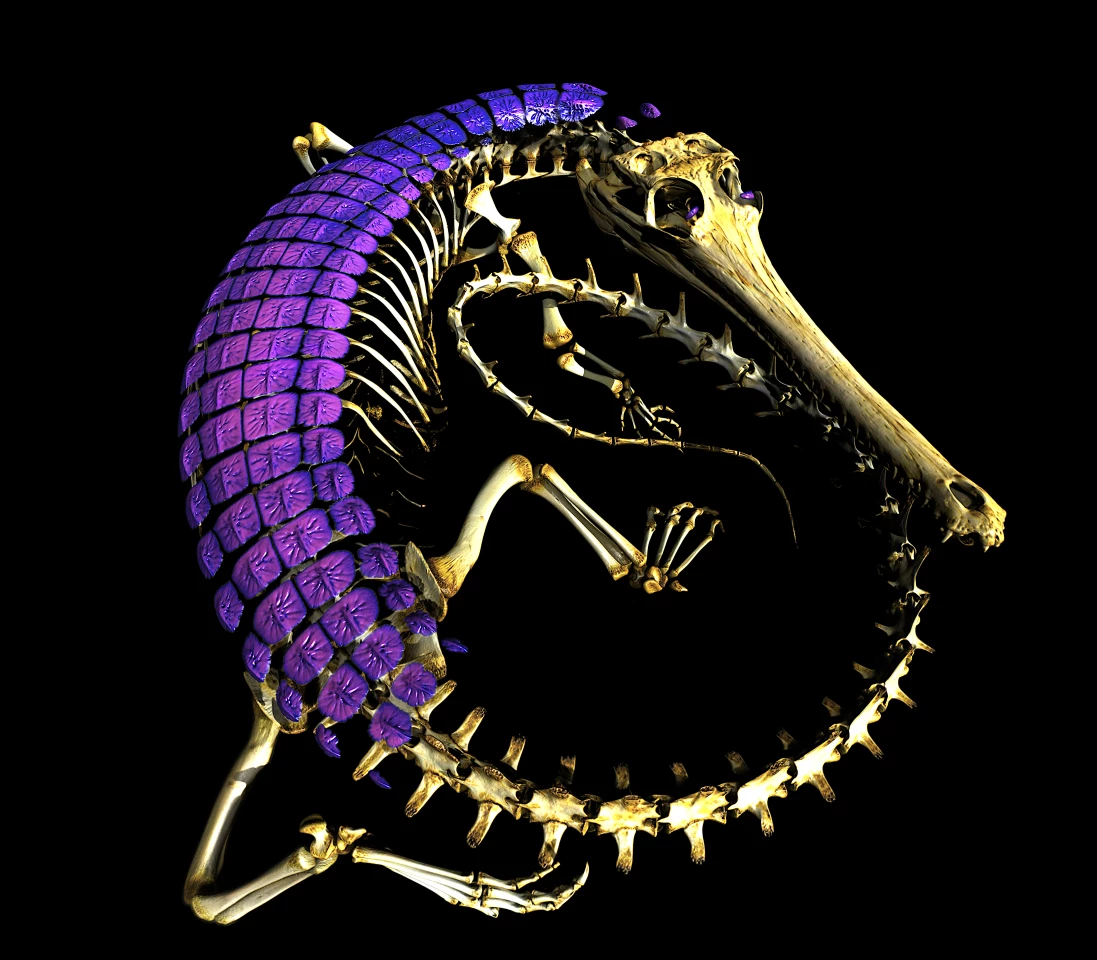

This is seen most clearly in monitor lizards, particularly in Australia, where several lineages appear to have re-evolved osteoderms during the Miocene. The biologists believe that early monitor lizards, including the ancestors of Australian monitors known as goannas, originally lost their osteoderms because an active, pursuit-hunting lifestyle favored speed and agility over heavy body armor. Millions of years later, some goanna species appear to have evolved a lighter, more flexible form of armor once again, possibly in response to new environmental pressures.

"This discovery also underscores Australia’s role as a hot spot for evolutionary oddities: a place where marsupials dominate, where mammals lay eggs, and now, where the only known ‘comeback’ of reptile osteoderms has occurred," said Roy Ebel, lead author and researcher at MVRI and the Australian National University.

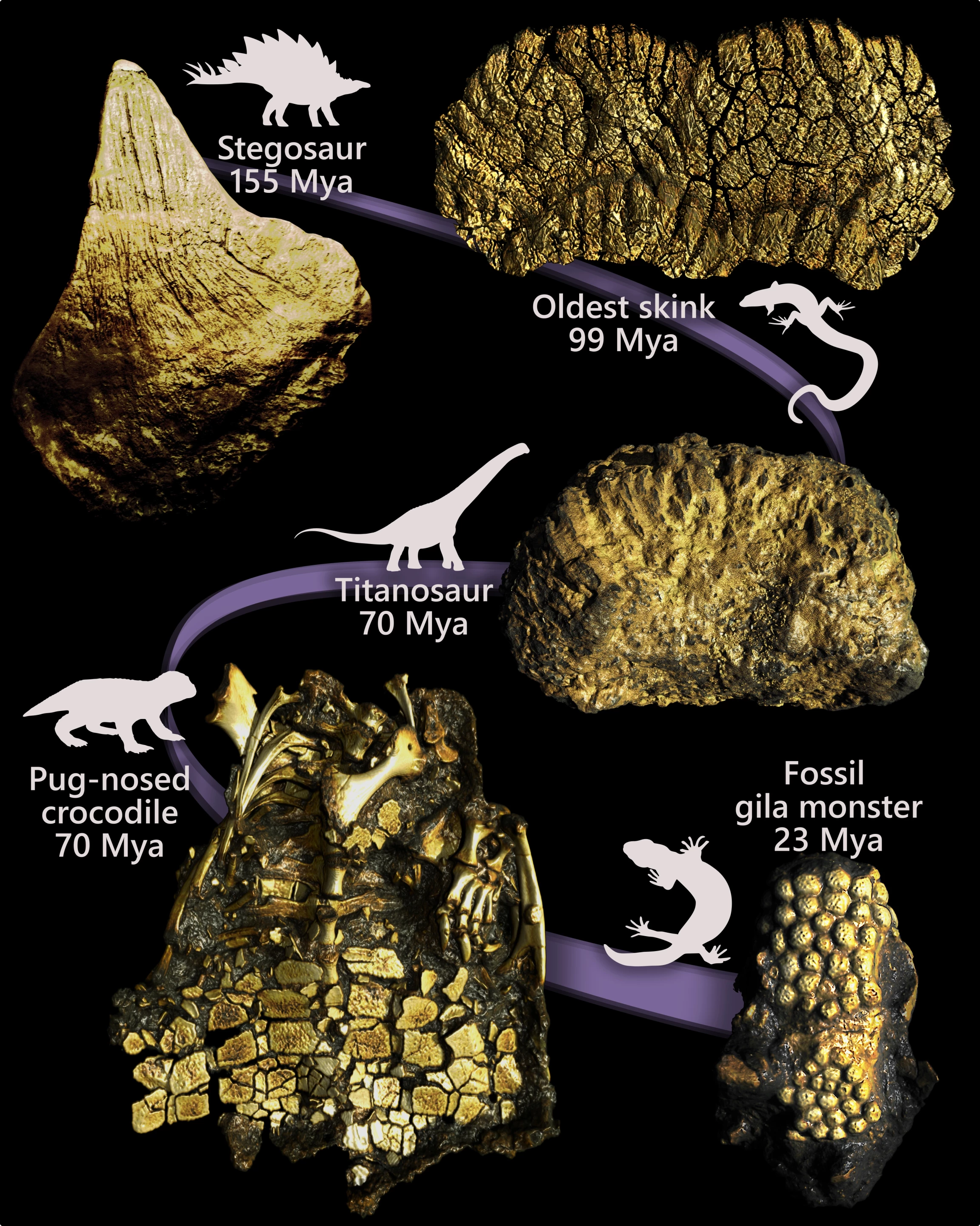

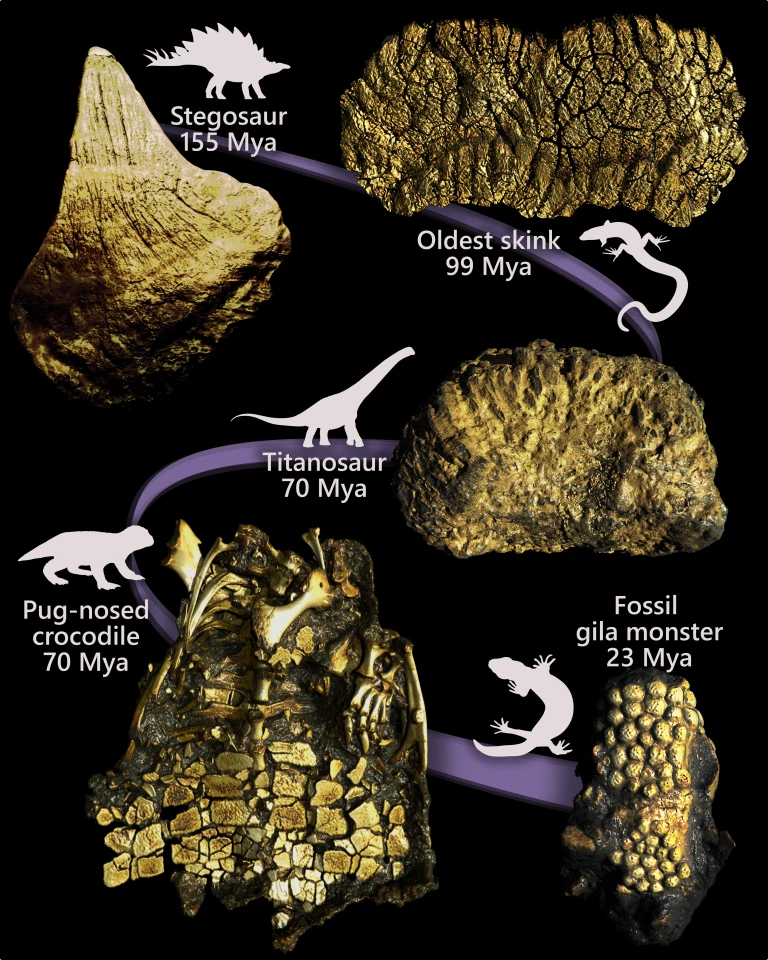

In the study, the researchers reconstructed the evolutionary history of osteoderms across squamate reptiles – the group that includes lizards and snakes – over a span of around 320 million years. By analyzing 643 living and extinct species, they came away with the most comprehensive picture yet of how these bony plates emerged, disappeared and, in some cases, reappeared.

These bony plates do much more than protect against physical attack, however. Osteoderms form within an animal's skin rather than as part of the skeleton, and serve many functions. In crocodiles, they play a key role in maintaining the animal's health during prolonged time spent submerged in water, releasing calcium that helps neutralize the buildup of acid in the blood. As such, these plates can act as armor, thermal regulators, calcium stores and water-retention structures. But despite this diversity of functions, their evolutionary origins have remained unclear.

In this study, the researchers used detailed CT-scan data showing where osteoderms occur in living lizards and compared it with a large molecular phylogeny and fossil record. They then applied evolutionary models accounting for adaptations at different rates through time, which enabled them to get a clearer look at when these bony plates were likely present or absent in ancestral species. The results show that the earliest lizard ancestors almost certainly lacked the armor altogether, with the trait remaining absent for tens of millions of years after lizards first evolved.

Through their work, they found that osteoderms arose independently at least 13 times across modern lizard groups. Most of these acquisitions occurred during a relatively narrow window in the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous, some 140 million years ago, just before many major lineages began to diverge quickly (in evolutionary terms, anyway).

They found that once osteoderms appeared within a lizard lineage, they usually stuck around – so much so that in most modern lizard groups, the loss of these bony plates was rare, effectively cementing armor as a long-term trait. One group, however, appears to be a notable exception. Monitor lizards appear to have lost osteoderms entirely around 72 million years ago, most likely as part of a shift toward a more active, chase-based hunting lifestyle. Much later, during the Miocene – roughly 17 to 20 million years ago – osteoderms reappeared in the common ancestors of several Australian and Papuan monitor groups, but in a lighter, looser form.

Why? Well, the scientists believe that as monitor lizards spread into new environments, particularly arid regions of Australia, osteoderms may have been reselected for different reasons – such as reducing water loss or reinforcing body parts for defense or climbing. In this sense, monitor lizards represent one of the clearest modern examples of evolutionary "re-innovation." And because of this, there's a patchwork of armored and unarmored monitor lizards walking the Earth today.

And, more broadly, these findings now add new complexities to our understanding of lizard evolution. As the scientists noted, it means animals like the Gila monster (Heloderma suspectum), native to the US and Mexico, can closely resemble Australia’s shingleback lizard (Tiliqua rugosa) in their armored appearance, even though they arrived at that similar morphology through very different evolutionary routes. In a way, it's similar to how flight is thought to have evolved independently at least four times, in insects, pterosaurs, birds and bats.

While a fascinating study for the zoologists and evolutionary biologists of the world, this new evolutionary map provides a strong foundation for future research into how and why osteoderms form, including the genetic and developmental mechanisms that have allowed them to arise repeatedly in different lizard lineages for different purposes.

"We have demonstrated here that squamate osteoderm expression is the product of multiple independent acquisitions," the researchers concluded. "Our reconstruction represents the presently most robust support for this hypothesis, and thus solidifies the foundation for future discussions on the underlying evolutionary mechanisms. Beyond this, our findings contribute towards a better understanding of the selective pressures and evolutionary trajectories that shaped present-day reptile biodiversity."

The research was published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.

Source: Museums Victoria via The Conversation