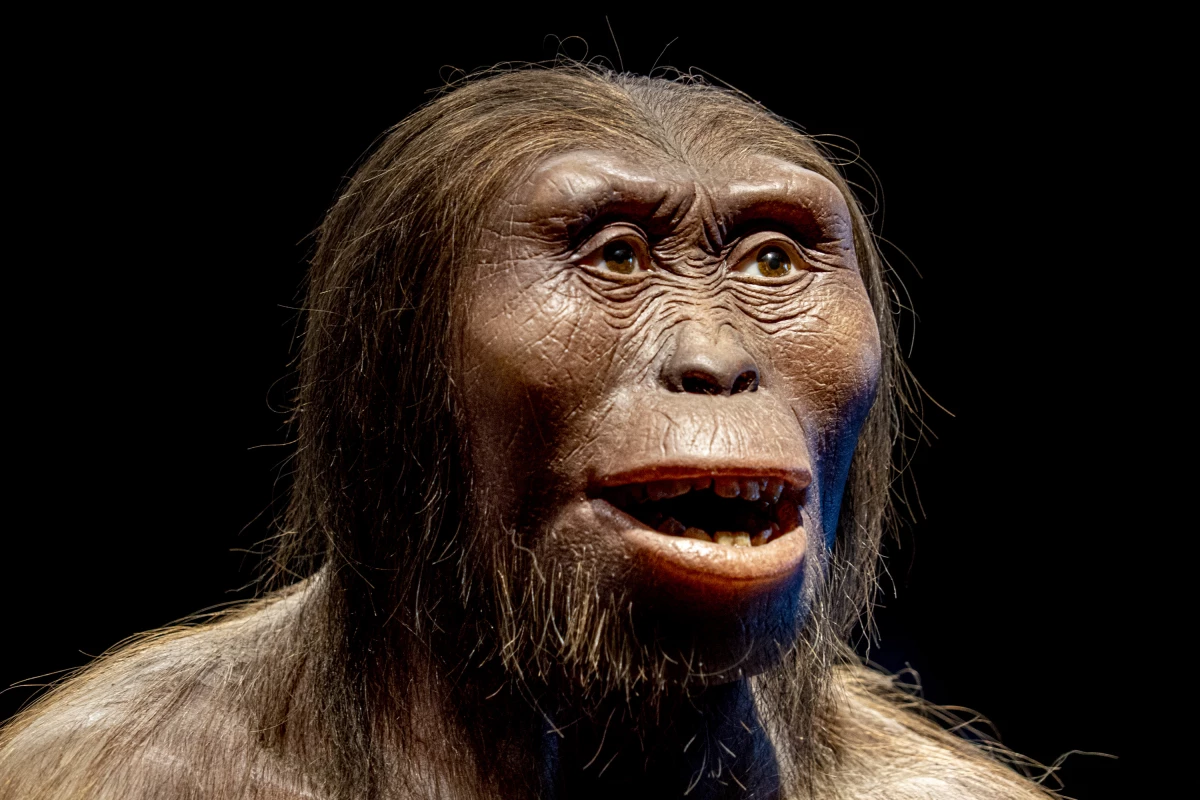

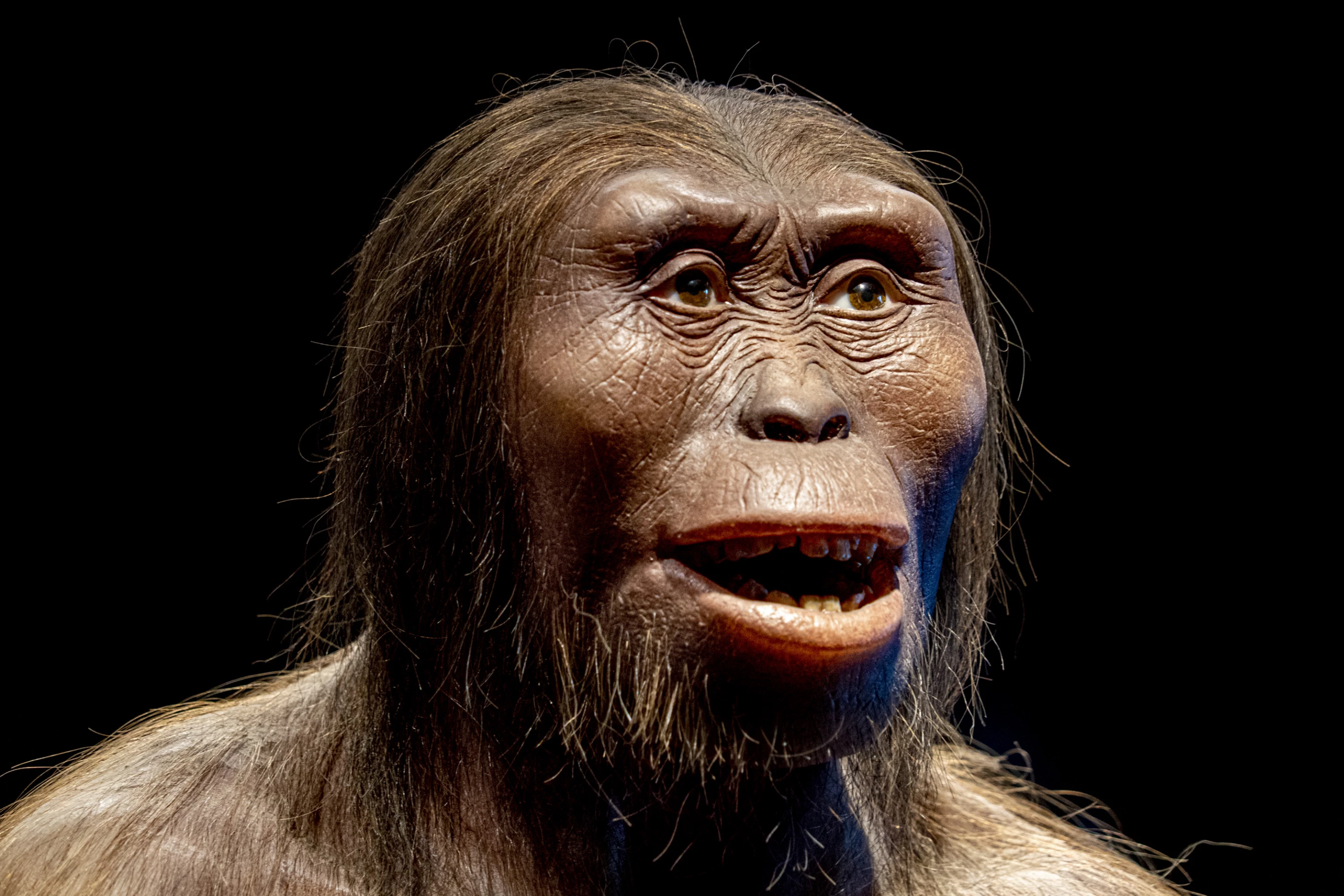

We may only ever have 47 of the 207 bones that made up the skeleton of this 3.18-million-year-old Australopithecus afarensis specimen known affectionately and widely as Lucy, but it’s been enough to make some incredible discoveries (and stir up more than a few controversies) that have informed human evolution.

The latest comes out of the University of Cambridge, where researcher Ashleigh Wiseman digitally reconstructed Lucy’s soft tissue in a 3D computer model for the first time. Recreating the musculature of the leg and pelvis, the imagery supports the supposition that this part-time tree-dwelling hominin walked completely erect, like humans, but more than three million years earlier.

Starting with human MRI and CT scans to map muscle pathways, Wiseman next focused on virtual reconstructions of Lucy’s bones and joints, and then married up cues from muscle "scarring" on the bones.

The resulting model shows how Lucy was capable of upright, erect locomotion but also possessed powerful leg muscles that facilitated her species’ half-land, half-arboreal lifestyle. Researchers believe the extra muscle power in the legs – 74% of the total mass compared to around 50% for humans – enabled A. afarensis to exploit both land and tree habitats.

"Lucy's ability to walk upright can only be known by reconstructing the path and space that a muscle occupies within the body," said Wiseman, from Cambridge University's McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. "We are now the only animal that can stand upright with straight knees. Lucy's muscles suggest that she was as proficient at bipedalism as we are, while possibly also being at home in the trees. Lucy likely walked and moved in a way that we do not see in any living species today.”

Lucy’s bones were uncovered by Donald Johanson in 1974, at Hadar, Ethiopia. Originally thought to be part of the Homo genus, four years later Lucy, officially known as AL 288-1, was given her own classification after other fossils found in Laetoli, Kenya suggested that the scientists were dealing with a new lineage altogether. Since then, researchers have been able to piece together that A. Afarensis, a hugely successful species, lived for around 900,000 years, between 3.9 and 2.8 million years ago.

Shortly after her discovery, bone analysis revealed Lucy – who was named after Lucy In the Sky with Diamonds by the Beatles, an ear-worm on the radio at the digging site in 1974 – to be female, most likely a young adult thanks to an erupted wisdom tooth and the fusion of specific bones, and around 1.05-m (3.3-ft) tall.

And while there’s been much debate over how she walked, this study reveals specific knee-joint and muscle structures that back the most popular theory: that she was fully upright, not lurched or knuckle-dragging, and still had the physical capabilities to head into the trees.

"Australopithecus afarensis would have roamed areas of open wooded grassland as well as more dense forests in East Africa around three to four million years ago,” said Wiseman. “These reconstructions of Lucy's muscles suggest that she would have been able to exploit both habitats effectively."

And while dating fossils has provided invaluable information regarding human evolution, being able to track specific movement provides a much fuller picture as to how, three million years later, Homo sapiens emerged and quickly spread across the planet.

"Muscle reconstructions have already been used to gauge running speeds of a T. rex, for example," said Wiseman. "By applying similar techniques to ancestral humans, we want to reveal the spectrum of physical movement that propelled our evolution – including those capabilities we have lost."

The research was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Source: University of Cambridge