While for us the discovery of a cavity might mean it's time for a trip to the dentist's office, their discovery in our early ancestors can act as an important indicator of ancient dietary trends. Fresh analysis of 54-million-year-old fossils has revealed the oldest known example of this among mammals, with a prehistoric primate by the name of Microsyops latidens found to suffer from relatively common dental cavities courtesy of shift towards a sugar-rich diet.

While studies into the frequency of dental cavities in humans has been a useful way to investigate dietary changes and uptake of carbohydrate-rich foods over time, these have rarely extended to extinct mammals. Researchers at the University of Toronto sought to change this by turning to the monkey-like primate M. latidens, which inhabited the Earth for half a million years before going extinct around 54 million years ago.

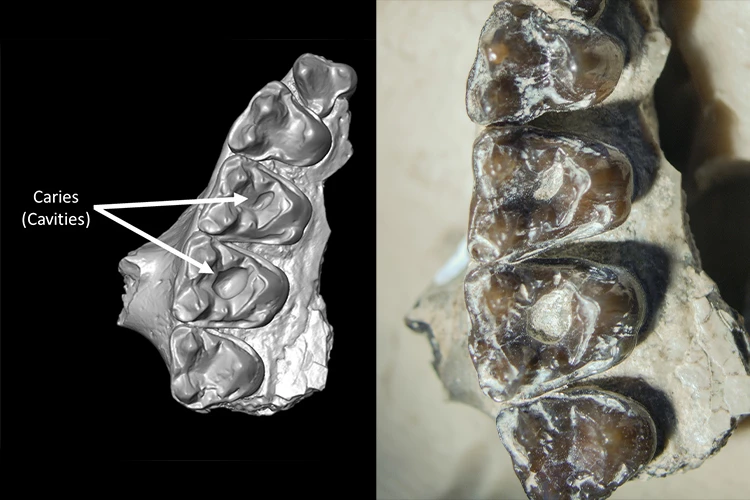

While there aren't many complete fossils of M. latidens to be found, there is a large sample of fossilized teeth that was dug up in Wyoming in the 1970s. These have been studied extensively since, including examinations of tiny holes in the teeth, but these little voids had previously been written off as physical damage incurred since the mammal's demise.

“These fossils were sitting around for 54 million years and a lot can happen in that time,” says Keegan Selig, lead author of the study. “I think most people assumed these holes were some kind of damage that happened over time, but they always occurred in the same part of the tooth and consistently had this smooth, rounded curve to them.”

Selig conducted a fresh analysis of the teeth of 1,000 individual M. latidens, using micro-CT scans that enabled him to effectively look inside the teeth. In doing so, the scientist confirmed cavities in 77 of them, producing the largest and earliest known sample of dental cavities in an extinct mammal.

Because the samples Selig was working with included specimens from different age groups, he was able to tease out some interesting insights around the dietary shifts of M. latidens. Fruits became more abundant around 65 million years ago and, while primates were likely eating them for some time before M. latidens came along, the prehistoric primate appeared to have an increasing appetite for the sweetness that they offered.

Among the older group studied, Selig discovered cavities in seven percent of the individuals, while they were found in 17 percent of the most recent group. So it appears that throughout their existence, M. latidens came to rely more heavily on fruits or other sugar-rich foods that provided them with high amounts of energy.

“Eating fruit is considered one of the hallmarks of what makes early primates unique,” says Selig. “If you’re a little primate scurrying around in the trees, you would want to eat food with a high energy value. They also likely weren’t concerned about getting cavities.”

The research was published in the journal Scientific Reports.

Source: University of Toronto