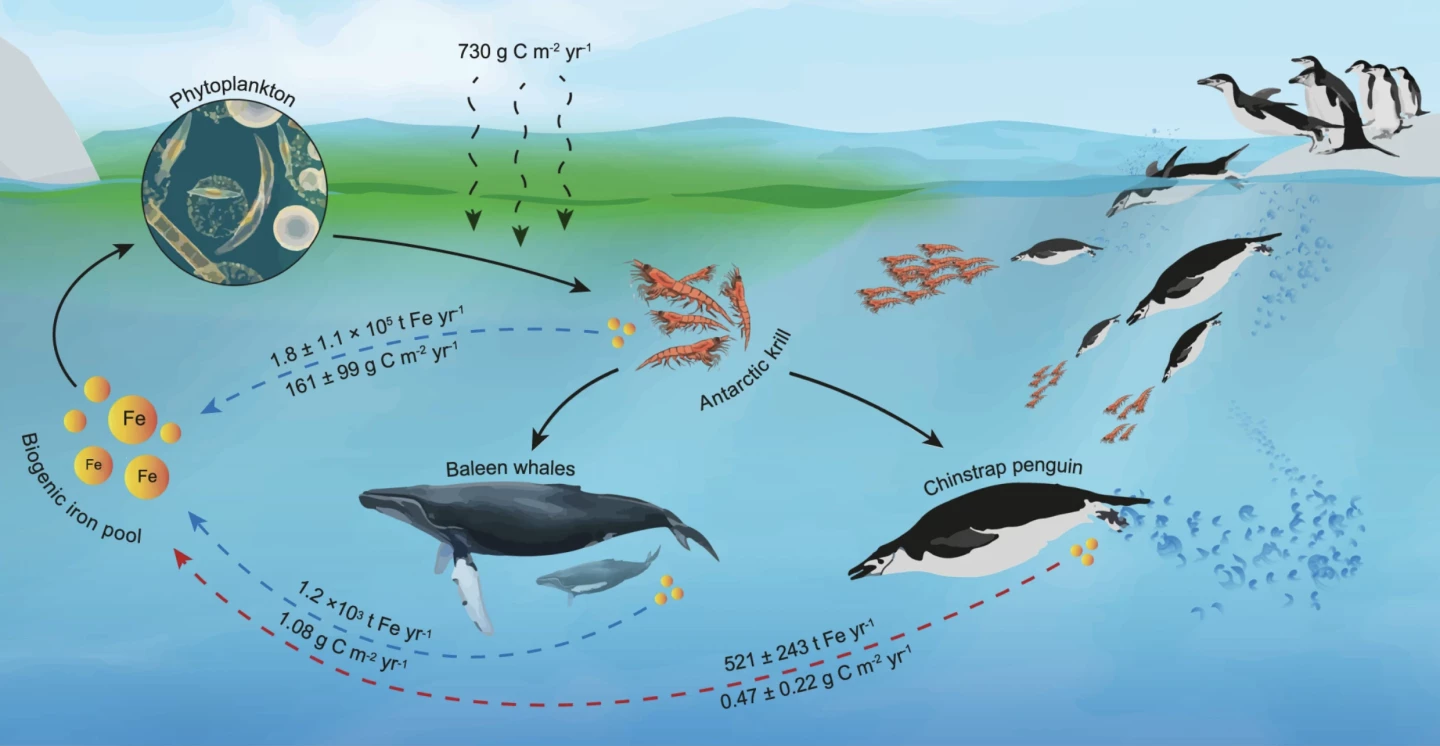

Large marine mammals such as baleen whales play a huge role in cycling iron through their marine environments, directly helping to boost phytoplankton growth and atmospheric carbon sequestration.

Now for the first time, scientists have discovered how a much smaller animal, with no less mighty a digestive system, has been pumping more than a million pounds of iron to the surface waters of the Southern Ocean each year, helping that essential plant plankton to thrive.

A research team led by Oleg Belyaev from the Institute of Marine Sciences of Andalusia (ICMAN) has found that the world’s population of chinstrap penguin (Pygoscelis antarctica) returns more than 574 tons of the crucial metal to the Antarctic waters every year via its guano, the product of the accumulation of their excrement.

It’s the first time the birds’ huge role in iron cycling has been studied, and it underpins the delicate interconnectedness of the ecosystem. The researchers believe that despite the heavy lifting the penguins are doing to sustain ocean health, their population has declined by half since the 1980s, resulting in half the nutrients flowing back into the sea.

Chinstrap penguins occupy remote and rugged areas along the Antarctic Peninsula and on South Atlantic islands. To measure the birds’ iron output, the researchers mapped colonies by drone, and one on Deception Island had its poop volume measured. Further chemical analysis revealed the high concentration of iron in the guano, equaling around 3 mg per gram.

Penguins famously produce a significant amount of excrement, so much so it can be seen from space.

Iron is vital to the Southern Ocean; it provides nutrients for phytoplankton that many species feed on, including krill. Antarctic krill, which can produce swarms in the number of trillions, makes up a significant part of the chinstrap penguin’s diet. As the significant amount of guano they produce returns to the ocean, it provides an easily available iron source for the life cycle.

Iron also plays a key role in carbon capture, as plentiful photosynthetic phytoplankton provides the Southern Ocean an enhanced ability to absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. This ocean may only cover about 6% of the planet, but it helps regulate global climate and stores captured carbon in its deep-sea sink.

The study also opens the door to more research into other penguin species’ role in this vital cycle. The chinstrap penguin is closely related to two other species, the gentoo (P. papua) and the Adélie (P. adeliae), who also have a diet rich in krill. While the chinstrap is of Least Concern on the IUCN species list, the others, with a much smaller population, are now Near Endangered due to their numbers decreasing.

While the chinstrap penguins, which can stand around 30 in (76 cm) tall and weigh more than 11 lb (5 kg), still number around 3.42 million, it’s half their numbers of 40 years ago. The decline is believed to be linked to climate change, which is impacting the distribution and biomass of the all-important krill. An earlier study deemed this species the “marine sentinels”, for the role the birds play as environmental-change indicators.

The researchers hope their study helps raise awareness of the direct ecological impact the penguins have on sustaining life in the waters surrounding their habitats.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Institute of Marine Sciences of Andalusia via Scimex