Researchers at Northwestern University have made a breakthrough in identifying a way for Alzheimer's disease to be treated far more effectively in the future – using the brain's own immune cells.

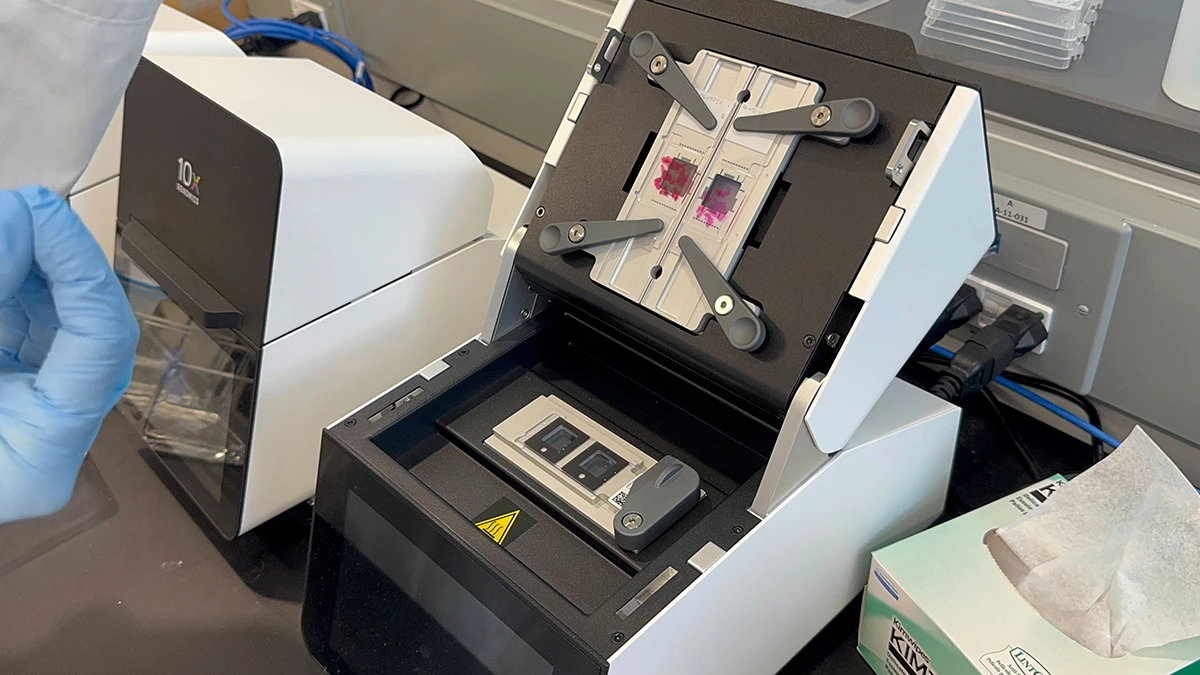

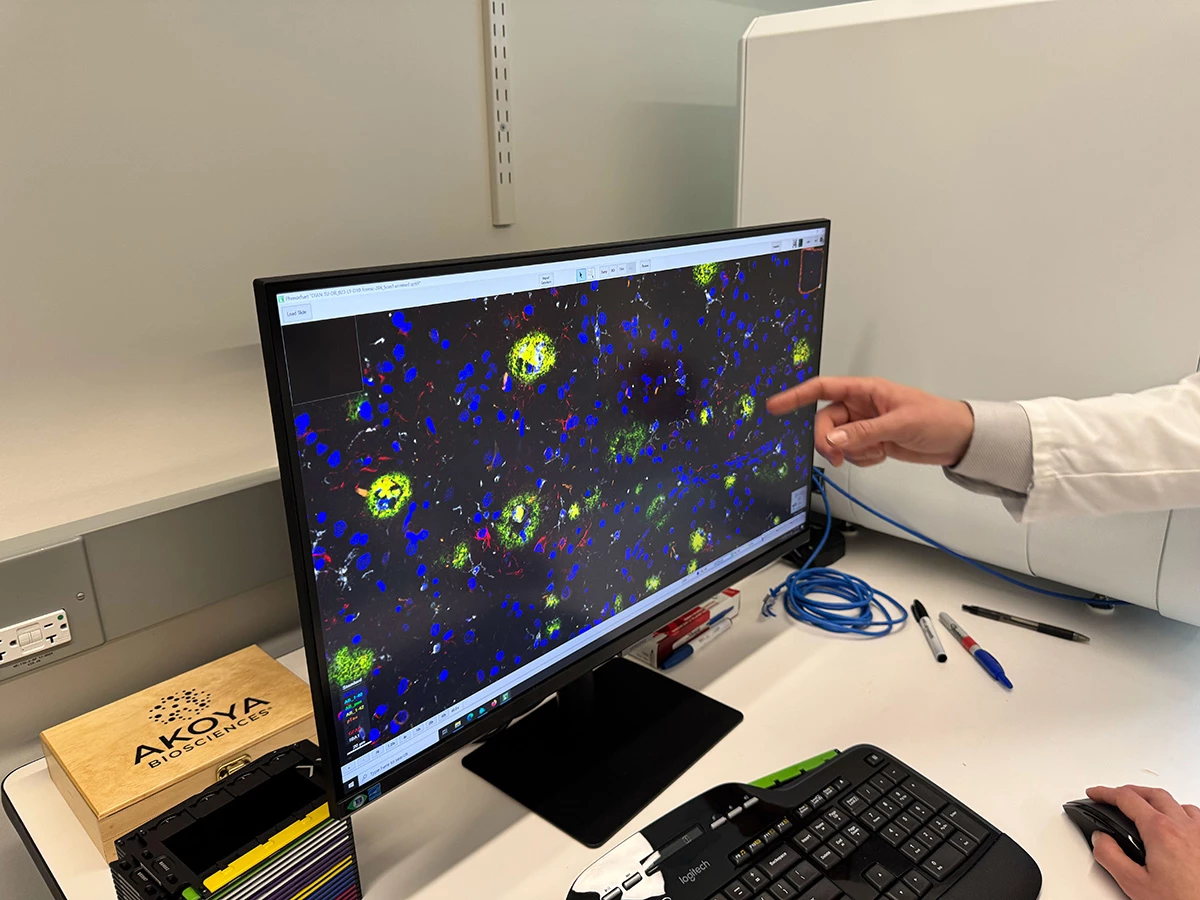

The scientists at the Evanston, Illinois-based university leveraged a new-ish technique called spatial transcriptomics on human clinical-trial brains afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease. The method of examining tissue helped pinpoint the specific spatial location of gene activity inside a sample.

Alzheimer's disease is caused in part by Amyloid-beta protein clumps forming outside of neurons as plaques, which can lead to the malfunctioning of tau proteins; these and other factors impede normal brain activity.

Using the new method to analyze brain tissue from deceased people with Alzheimer’s disease who received amyloid-beta immunization and comparing it to tissue samples from those who did not, the team noticed that the brain’s immune cells (known as microglia) clear plaques, and subsequently get to work restoring a healthy environment in which the brain can heal.

David Gate, an author of the paper that's appeared in Nature Medicine today, explained that this newly observed mechanism of the immune cells adapting their role in helping the brain recover could inform the development of treatments that "circumvent the whole drug process and just target these specific cells.” That might be a while away, as we don't yet have a way to target only those cells, but Gate notes that methods to do so are continually improving.

So no, it's not a cure yet – but it sounds like a meaningful advancement in our evolving understanding of how we might address the complexities of Alzheimer's. It could also enable treatments that don't result in harmful potential side effects common to currently available drugs. Every step forward is a major win against this condition that, along with other dementias, is estimated to affect nearly 80 million people worldwide in the next five years.

It's heartening to see studies like this grow the list of developments in understanding Alzheimer's. Last month, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh revealed a biomarker test that can spot small amounts of clumping tau protein in the brain a decade in advance of them appearing prominently in brain scans as a cause of Alzheimer's. We also recently saw the disease being categorized into five subtypes for more targeted treatment.

Source: Northwestern University