Another study has added to the growing evidence linking the cold sore-causing herpes virus with Alzheimer’s disease. It also found that those people who used herpes treatments such as antivirals were 17% less likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Evidence of a link between herpesviruses and the development of Alzheimer’s disease has been growing. Indeed, the idea that herpesviruses contribute to Alzheimer’s appears to have moved from being a controversial fringe theory to one that is more mainstream.

A new study by the American biopharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences Inc. and the University of Washington’s Department of Medicine (UW Medicine) has added to the mounting evidence, finding an association between herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Importantly, they’ve also found that using antiviral medications after diagnosis can reduce that risk.

Worldwide, about 35.6 million people live with dementia, with 7.7 million new cases diagnosed each year. Alzheimer’s disease represents 60% to 80% of dementia cases. As the global population continues to age, the incidence of Alzheimer’s is expected to rise unless a disease-modifying treatment is developed.

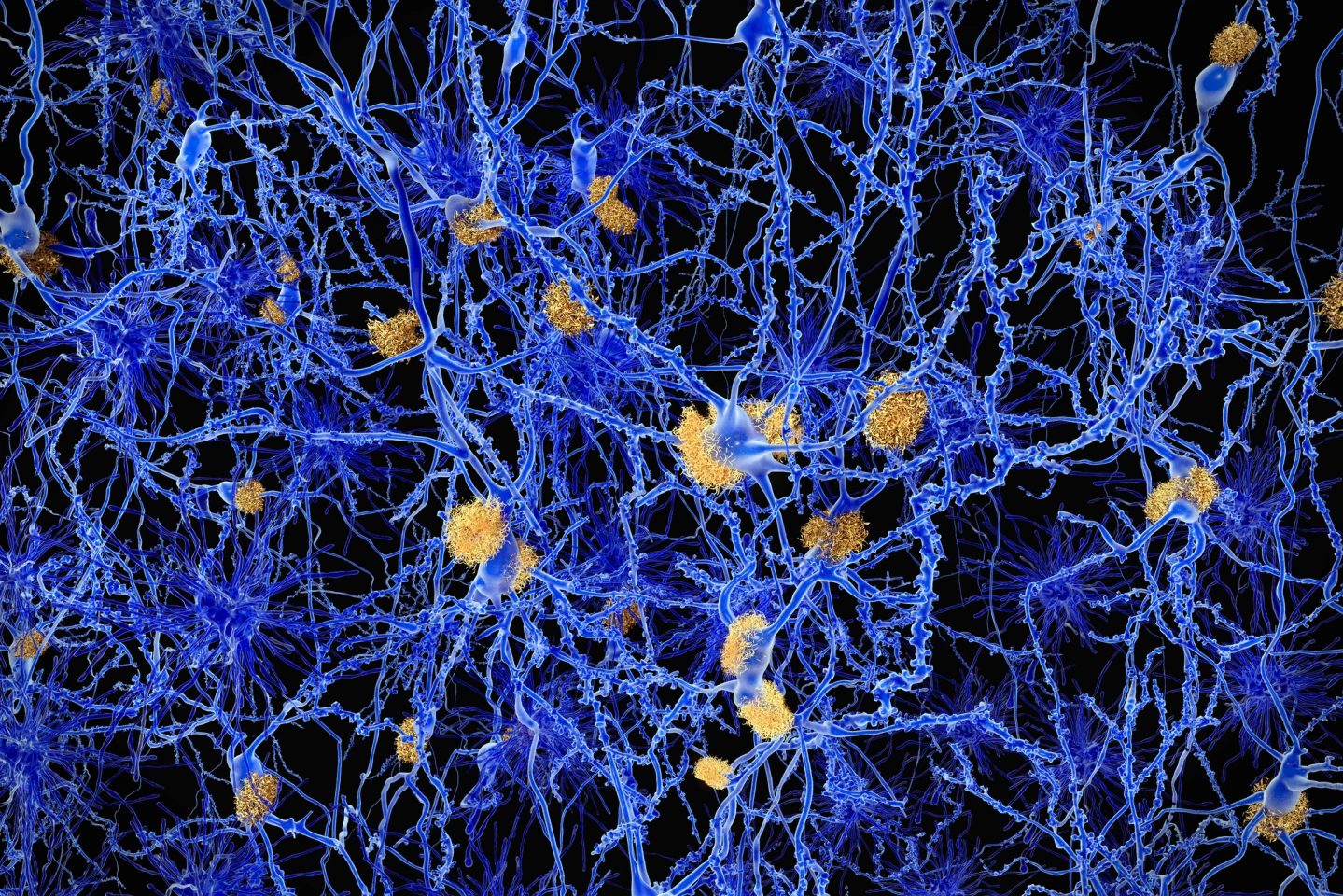

Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by particular brain pathology: accumulated amyloid-beta plaques and toxic tau tangles. While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s isn’t known, it’s been hypothesized that the very common HSV-1, the virus that causes cold sores, might contribute to Alzheimer’s disease by causing a chronic infection in the brain, leading to inflammation and neurodegeneration.

The researchers identified 344,628 patients aged over 50 with Alzheimer’s disease or other Alzheimer's-like dementia diagnosed between 2006 and 2021 from the IQVIA PharMetrics Plus claims database, which contains information on medical and pharmacy claims for over 215 million individuals in the US. Each of these patients was matched with a control with no history of neurological disorders. Diagnoses of HSV-1 and other herpesviruses, including HSV-2, which commonly causes genital herpes, varicella-zoster virus (VZV, aka chickenpox/shingles), and cytomegalovirus (CMV). The researchers also obtained information on antiherpes treatments, like antivirals, given after diagnosis with HSV-1.

A history of HSV-1 diagnosis was seen in 0.44% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease compared with 0.24% in the control group. People with a history of HSV-1 were found to have an 80% higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s compared to those without HSV-1 (after adjusting for factors that might affect the results). For those with HSV-1, using antiherpetic medications was associated with a 17% lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease than those who didn’t use them. This result was found to be statistically significant, meaning it’s unlikely to be due to chance.

“In summary, we find an association between symptomatic HSV-1 infection and AD [Alzheimer’s disease] using a large claims database from [the] USA and highlight antiherpetic therapies as potentially protective for AD,” the researchers said.

The study’s findings have drawn comment from experts, including Bryce Vissel, PhD, a Professor in the School of Clinical Medicine at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and head of the Clinical Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine (CNRM) initiative at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney.

“Our research team at St Vincent’s has been asking: what if common viruses are helping cause Alzheimer’s – and we already have ways to fight back?” said Vissel, who is a specialist in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s. “A number of recent studies are now adding weight to that idea. These viruses are incredibly common. Most people are infected in childhood. They retreat into the nervous system and stay there for life. Under certain conditions – stress, inflammation, immune decline – they can reactivate. This may trigger an inflammatory cascade in the brain that leads to the synapse loss and memory decline characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

“We’re not saying viruses explain everything. But they may be central to it. This is no longer a fringe theory – it’s the next phase of Alzheimer’s research, and we’re pursuing it … This [the results of the present study] aligns with the broader shift we’ve long argued is needed in the field. For decades, Alzheimer’s research focused almost exclusively on amyloid – the protein that builds up in affected brains. But despite billions in investment, anti-amyloid drugs have consistently failed to prevent or reverse the disease. An increasingly supported view – and one we’ve championed – is that amyloid might not be the cause, but a response: part of the brain’s defense against microbial threats. If that’s true, clearing it without removing the trigger may be ineffective.”

Professor Bruce Brew, Consultant Physician and Neurologist from UNSW and Professor of Medicine at the University of Notre Dame Sydney was more circumspect.

“This is an important study that adds to the existing evidence that herpes simplex and herpes zoster infection are risk factors and possibly exacerbating factors for Alzheimer’s, but unlikely the cause,” Brew said. “The data show a modest association between a diagnosis of herpes simplex as well as herpes zoster and Alzheimer’s, especially in the elderly. Further, there was a modest protective effect of antiherpes medication.”

Some of the limitations with the present study were its retrospective nature, an inability to validate diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease, and the inability to determine important details about the antiherpes medications given, such as dose and duration. Nonetheless, the findings do accord with other studies that found a link between herpesviruses and Alzheimer’s disease. Further research is needed to ascertain causation and might, eventually, assess whether antiviral therapies are an effective treatment for dementia.

Interestingly, a study led by the Korea University College of Medicine (KUCM) was recently published in the journal Theranostics. In it, researchers used a novel drug, ATL001, to improve the function of HSV-1-infected microglia, the brain's immune cells, which subsequently reduced neuroinflammation. The drug also enhanced the microglia's ability to clear amyloid aggregates from the brain.

The study was published in the journal BMJ Open.

Source: Gilead Sciences Inc. via Scimex