British company Camcon Automotive has built the first fully electronic engine valve system, uncoupled from the crankshaft, that offers unprecedented control over the combustion cycle. On top of power and emissions improvements, it also opens up some weird and wonderful capabilities we've never seen before, such as giving 4-stroke engines brief 2-stroke power boosts.

Variable valve timing is nothing new. It's been obvious to manufacturers for decades that the optimal valve operation is different when the engine's doing different things, and that changing the timing, lift and duration of the valve events on an engine to suit different scenarios can result in power, torque, efficiency and emissions advantages.

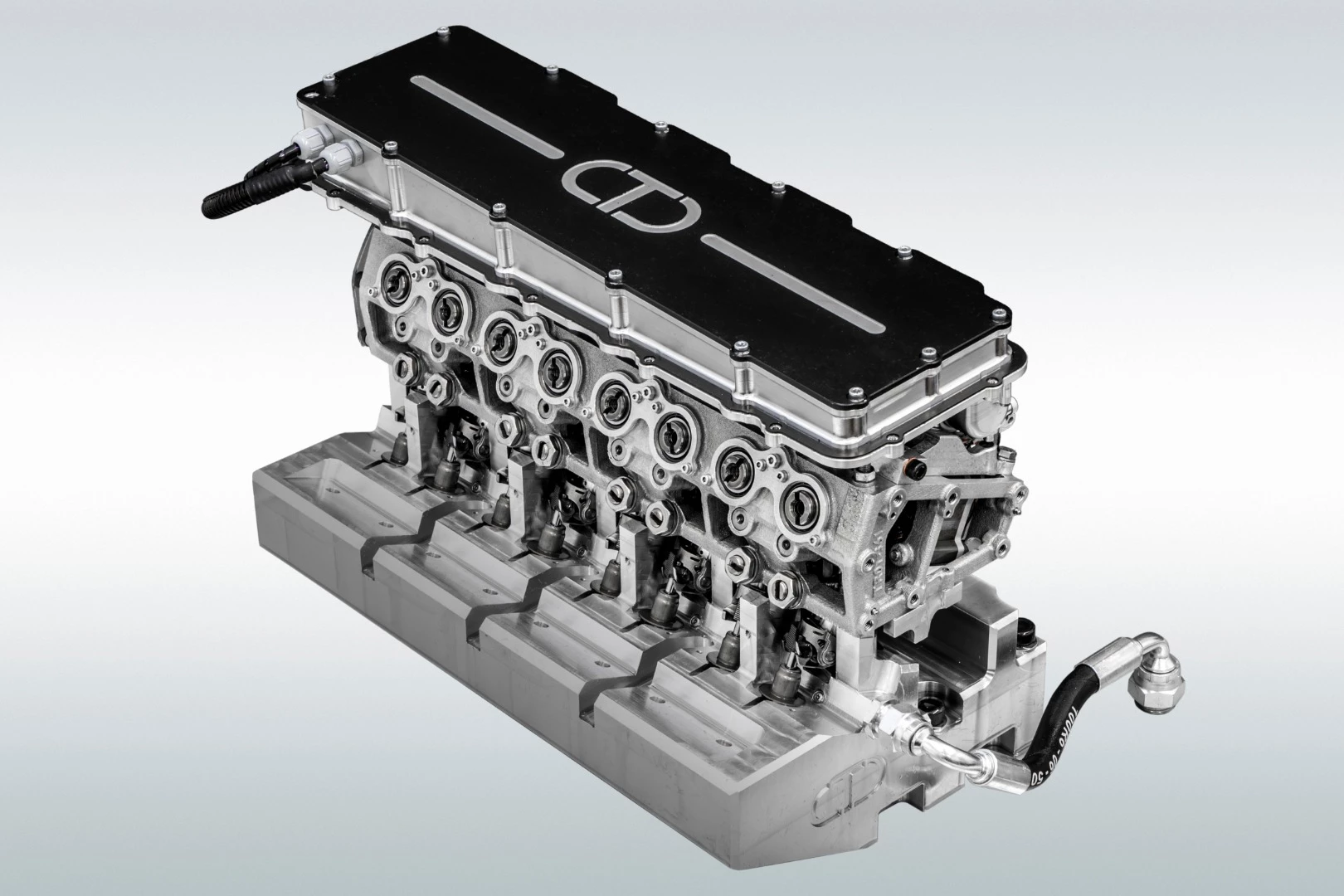

What makes Camcon's system different is that it allows complete, instant and unrestricted control over exactly what any intake or exhaust valve is doing, at any time, regardless of what the engine itself is doing. That's because Camcon's IVA (Intelligent Valve Actuation) system is fully electronic, with no mechanical attachment to the crankshaft.

There are no timing belts or valve springs, with each valve getting its own miniature camshaft, complete with a desmodromic system that opens and closes the valves precisely and mechanically. And instead of being driven off the crank, each valve's camshaft is controlled by an electric motor.

These motors can rotate either way with total precision, and for a given valve event they can rotate through fully to give 100 percent of the available valve lift, or they can stop part-way through and return back to closed, so you can get literally any degree of valve lift you want, at any time. There's a video at the bottom of the page to give you a better visual explanation.

The system knows the position of the crankshaft at all times thanks to a rotary position sensor – in fact, the whole system runs under real-time, closed-loop control, so that valve events are timed perfectly against what the motor's doing.

"What that means," says Camcon COO Mark Gostick on a Skype call from his Cambridge office, "is we can give the engine exactly what it wants at low revs, and exactly what it wants at higher revs, and anywhere in between, and you don't have to compromise at all. You can change timing, you can change duration, you can change lift, you can even shape the events if you want. You can do double events. You can change the profile of your camshaft between one event and the next. You can go from your idle setting to 100 percent throttle in one revolution. You can do pretty much anything. You've got what we like to call a digital crankshaft."

It seems like a simple enough idea, moving to electronic control of the valves. So why hasn't it been done before?

"Electromechanically, you could look at it and ask 'why didn't you do that 20 years ago?'" says Gostick. "The difference is in the electronics that control it. What's happened in the recent past is that there's now sufficient processing bandwidth at a low price that can tolerate top of engine conditions, so you can actually put real time control on top of these motors."

The low-hanging fruit

Naturally, this lets car manufacturers run highly optimized versions of the same tricks they've done with traditional VVT systems previously – bit of extra torque down low, bit of extra horsepower up high, improved emissions. And the company has several bench engines running, as well as one built into a drivable car to demonstrate these kinds of simple advantages.

"We've got thousands of hours of dynamometer time, showing what we can do," says Gostick. "This is on the inlet side only – we decided to do the inlet side first because it's lower risk, but it has the most well-known benefits. Nobody's ever done variable valve timing on the exhausts, so the benefits are less well understood.

"In terms of dynamometer results, we've only done what's called steady state testing, where the thing is running at a fixed point or a series of fixed points. And against the Jaguar Ingenium, which is pretty much a state of the art petrol engine, we got CO2 benefits of up to 7.5 percent improvement. We believe with transient calibration and all that kind of stuff where we integrate it properly into a vehicle, we could show CO2 benefits of up to 20 percent. We're now in the process of making 16-valve engines, that's inlet and exhaust, and we'll be running that when it's ready."

More integrated possibilities

Camcon believes the benefits of this IVA system will really begin to add up once it's more tightly integrated into the car, particularly in the hybrid space. And Gostick certainly doesn't think the gasoline engine is anywhere near the end of its rope.

"People might say 'why are you still jumping through hoops on internal combustion engines, when everybody knows it's all going to be batteries?' Well, actually, if you talk to people in the industry and look at what's happening, most take the view that for the foreseeable future, most vehicles are going to have some form of internal combustion engine on board, be it plug-in hybrids, regular hybrids or whatever. And those hybrid vehicles still need to have very well tuned, high performing engines.

"If you've got a plug-in hybrid, you've got built-in intelligence on board that decides when to run off the battery, and when to run off the engine. Part of that calculation is how much energy it might take to re-start the engine. Restarting the engine takes a lot of battery each time, and then you've got to recharge the battery from the engine, which has consequences for the overall performance.

"But if you've got complete control over the valves, you can substantially reduce the amount of energy it takes to restart the engine. Because you can open the valves right up, so the starter motor just has to overcome friction, as opposed to compressing the gases in the chambers as well. By doing things like that, you can change the equation for when you re-start the engine.

"In a hybrid vehicle, with a given size battery, you can substantially increase its pure electric mileage capacity. We have a sense of it, we haven't bagged it up with real world examples yet, but typically plug-in hybrids have a pure electric range around 30 miles (48 km), something like that. We think we can probably get that to 40 or 50 (64 or 80 km), which is reasonably substantial. That's not just by using this start-stop thing, that's including some other ideas we've got around things like the air conditioning and other integrations.

"Hybrids are very interesting, because you can use electricity at some points, and internal combustion at other points, and if you optimize that, you can play some really interesting tricks, like deciding when to run the valve train off the battery, and when to run it off the alternator. Sometimes the electric system produces too much electricity, more than it can store, so you can use it in different ways. We're just starting to scratch the surface of them really.

"It's things like this, which are not obvious ... I mean, we can talk about the headline performance improvements you can give on a raw engine, but actually there's practically the same benefit again if you do the integration into the vehicle properly. You can play new tricks that you couldn't when the valves were linked to the crankshaft."

Getting really crazy with digital valves

While the above kinds of techniques do push a little into uncharted territory, going further with the IVA offers some truly out-there potential.

"One of the things you can do with this valve train is to do all sorts of relatively off-the-beaten-path combustion approaches," says Gostick. "So people are talking about deep Miller cycle and Lambda 2 and HCCI and this kind of stuff, things where you need very precise control over the combustion conditions to do them. We regard ourselves as an enabler.

"The two-stroke thing is slightly off to the side. The trend in car engines has been downsizing, downspeeding, all these kinds of things. All of which work fine when you're cruising on the motorway, but when you're trying to pull away really quickly from traffic lights or at a roundabout or whatever, and you put your foot down, that's when you really feel like you've got a small engine in a big car.

"What you can do – in principle at least, we haven't demonstrated it yet – is you can turn the vehicle, for short periods of time, from four-stroke operation into two-stroke operation. That essentially doubles the power output. It gives you, when you need it, a burst of power. In principle, you can do it, for a short time period that's limited by heat and lubrication factors. When we get actuators on the exhaust valves of our test engines, we'll be trying it.

"Two-stroke is one of those things that kind of is, was and always has been the future of internal combustion engines. There's renewed interest in two-strokes for a number of applications and we might be able to do something interesting there, just for very short periods, so you can get over this problem with small engines in big cars.

"Going to the opposite end of the spectrum, you could do something called 12-stroking," Gostick continues. "So if you're on the motorway and you're cruising along, you can put it in 12-stroke mode, meaning that every cylinder only fires every third stroke. But it does it over the whole engine, like a roaming cylinder deactivation if you like.

"A lot of cylinder deactivation just knocks off one or two cylinders, and because it's mechanical, it always knocks the same ones off, and when you re-engage them, you get hydrocarbon spikes because there's engine oil building up in the cylinders while they're not firing. If you do 12-stroking, you keep all the cylinders warm and you stop this build-up of lubricant, so you get the benefit without the penalty when you re-engage four stroke again.

"Once you have this degree of control, you can start to play all sorts of tricks. Once you've got the exhaust valves hooked up, you can also port the exhaust, so you can do quick catalyst warmup, you can play tricks with turbochargers, you can do all sorts of things."

Where Camcon's digital valve system is at commercially

While Camcon has its own test engines and demonstration car up and running, this technology won't reveal the extent of its benefits until auto manufacturers start running with it and fully integrate it into their systems.

The company has spent significant time working with Jaguar Land Rover, publishing a paper together at the prestigious Aachen engine conference in Germany last year. And while that collaboration continues, Gostick says the company sees its biggest opportunities in Asia.

"We're focusing on the far East: Japan, Korea, China, purely because from an industry perspective we feel those are the areas that will be most receptive to what we're trying to do at the moment," he says.

"It's a combination of the political environment, their attitudes to innovation and risk, and how mature they are in terms of thought process about future powertrains. In Europe at the moment, because of what the Commission is doing, all the car companies are running around saying 'batteries good, batteries good,' and a lot of the Asian companies have been through it in a more thoughtful way, and come up with a portfolio approach where you've got battery vehicles, you've got hybrid vehicles, and for other applications there's pure ICE vehicles. I think they're further along in their thought process about what the future powertrain looks like."

The company has just introduced a version of the IVA tech that runs on the kinds of single-cylinder development engines that OEMs and tier one automotive suppliers use to test and develop their motors, to make it as easy as possible for car companies to experiment with the technology.

Camcon believes that the digital valve train can be a diesel-killer for passenger cars, offering diesel-level efficiency and fuel economy with none of the particulate and NOx emissions that have seen diesels fall spectacularly out of favor in Europe in recent months.

"In terms of cost, we can't go into specifics yet, but it's certainly less than the cost of doing diesel rather than petrol," says Gostick. "Diesel sales in Europe in the last quarter are down by 17 percent or something. It used to be 50 percent or more of total car sales, now it's down in the 30s thanks to Dieselgate and other factors. One of the consequences from that is that CO2 emissions in Europe are now going up again, because people are turning back toward gasoline engined cars that put out more CO2 than the diesel engines do.

"That's why a system that can reduce emissions in petrol cars is a great thing to have right now. Ours is not a cheap system, but in the context of diesel, it's not an expensive one either."

On a less planet-friendly note, we'd like to see what happens when this technology gets into the hands of hardcore performance tuner types and race teams. This sounds like an opportunity for petrolheads to do some very interesting things with motors.

Check out the technology in the video below.

Source: Camcon Automotive

Update (Aug 13, 2018): As some commenters have noted, this system bears some similarities to the FreeValve system from Koenigsegg, as demonstrated in the Qamfree motor from Qoros – but we'd highlight that the FreeValve's electro-hydraulic-pneumatic actuation system uses valve springs instead of a mechanical system to close its valves. Thus, it's vulnerable to high-rpm valve float and doesn't offer quite the desmodromic precision the Camcon system does. However, it's fair to call the difference academic when it comes to roadgoing cars, whose motors rarely rev high enough to make that a problem anyway.