Owing perhaps to the difficulty and extreme cost of building virtual worlds that can be seen, heard, explored, and interacted with in multitudes of other ways, video games have long made use of procedural content generation and computation creativity. Epic space-faring BBC Micro game Elite generated its own star systems on the fly way back in 1984, for instance, while the likes of Minecraft, Diablo, and the SimCity series all similarly sport environments sculpted by algorithms. But artificial intelligence research is opening new avenues in the ever-evolving dance between human game developers and their algorithmically-intelligent tools. AIs can now create entire 2D and 3D games from scratch, unassisted, and that could be just the tip of the iceberg.

"I have a personal fascination with what technology can do," Michael Cook tells Gizmag. He's a Ph. D student at Imperial College in London and research associate at Goldsmiths College Computational Creativity Group. He makes things that make other things, exploring the limits to how much computers can be taught to create.

"Procedural content generation feels a bit like violating laws of the universe – creating something from nothing, again and again," he continues. "Of course it's nothing like that really, but you get a rush from seeing something appear suddenly."

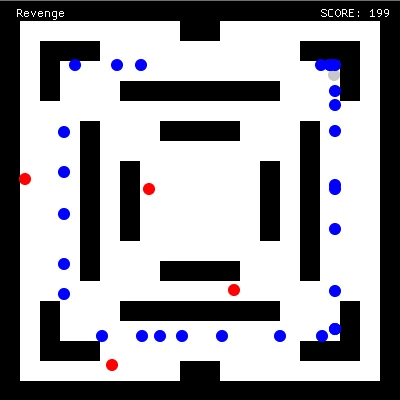

Cook's game designing AI ANGELINA ("A Novel Game-Evolving Labrat I've Named ANGELINA") has evolved steadily through multiple variations since 2011 just as it (not her), itself, evolves its own video games. ANGELINA at first created its own simple arcade games, then moved into Metroid-styled platformers and onto more unique fare.

Cook likes to ask questions that break people's assumptions. He sees value in challenging the status quo and looking for answers to questions in unusual places. ANGELINA is part of that.

For a while ANGELINA generated ideas by reading the Guardian website, maintaining a text file with the names of all the people known to it alongside a numeric value of its opinion of them based on its reading. It inexplicably developed a fondness for Rupert Murdoch during this time (because he's responsible, which is generally a good thing, albeit for things ANGELINA does not know are negative), all the while using its political not-quite-savvy to add texture to the 2D platformers and games with self-created mechanics that it designed in a process described in detail as part of a Eurogamer interview with Cook from 2013.

More recently, ANGELINA has participated in game jams such as Ludum Dare, where it competed against human players, and it's made the jump to creating 3D games using the popular Unity engine. As part of these initiatives, ANGELINA learned how to design a game from a single theme word or phrase – something abstract like "alone" or more straightforward like "fishing" or "you only get one" (which was the theme for Ludum Dare 28).

ANGELINA can select theme-appropriate graphics and sound effects with help from a multitude of databases and other sources, then layer those onto unspectacular maze games that have level layouts and mechanical rules that ANGELINA sets with code it writes itself. You can see a video below of Cook playing through and commentating on the design choices that ANGELINA made in creating its Ludum Dare entry, To That Sect.

For 10 days in November, ANGELINA took a backseat to other procedural-generation game projects. Cook ran PROCJAM over that period, which is described as "a game jam about making stuff that makes other stuff" that attracted 138 submissions ranging from procedurally-generated games to weather, new Pokemon and tile generators. (And even, remarkably, a procedural first-person shooter meant to be printed out on paper and played on a tabletop.)

Cook got a kick out of seeing the creativity and collaboration on show at PROCJAM, in large part because it drives more discourse about procedural generation and game design. "The successes are pretty modest," he notes, but his work has already started to get people thinking about these problems in new ways.

For game design, artificial intelligence is another way of tackling problems. In a world where most current genres and core gameplay mechanics have been around for years, refined again and again to a sharp point, an AI could bring something new to the table.

"AI will invent genres that humans could never have possibly conceived of, I believe," says Cook. "One day people will steal ideas from software, not because they want the fame or the pride, but because it's the current mobile trend and it's too good not to steal. It's a cynical and sad aspect of the future, perhaps, but also I like to think it would be a moment of huge validation for AI."

In the meantime, AI's benefits will be more subtle.

"Computers are quite good at considering options equally," explains Cook. "They can't forget things, they don't get tired, they don't get confused by emotional needs." People, however, are prone to fatigue and conscious or unconscious biases. An AI can show them something that they stopped considering as an option earlier in the process.

The catch, however, is that the two need to work together for best results. AI and human, collaborating.

Computers can be trained to make aesthetic decisions about which creative solution is "better," but as Georgia Tech associate professor Mark Riedl explains, "What happens is the machine starts to learn our preferences, but it doesn't necessarily learn to generalize very well. So then what happens is it starts to just mimic us."

"And when you think about creative exploration," he continues, "the great creators of the world are the ones who are actually able to violate expectations and preferences and cultural norms and find something new that was valuable but then becomes part of our cultural norms."

Riedl runs the Entertainment Intelligence Lab. His chief research interests are in interactive storytelling and automated story generation, though he also dabbles in other areas of AI and computational creativity. We'll dig deeper into his background and thoughts on story generation later in the series, but suffice to say that there's a heavy crossover between that and the applications of creative AI in video game development.

AI creativity has two main avenues in game design, Riedl argues. First, there's creativity support, wherein the intelligent design tools help people to more quickly generate level layouts, environments, characters, and so forth.

"A classic example of this is a computer program called SpeedTree," he says. "All it does is put unique trees in a 3D environment. That saves the designer lots of time because they don't have to hand place every single tree. They don't have to make every tree look a little bit different manually."

Other examples might be procedurally-generated virtual cities or racetracks, or, as mentioned above, tiles or Pokemon or other creatures that could then be altered and tuned as desired to fit the preferences of the designers (hopefully for the betterment of the game's balance and cohesiveness). At the extreme end, there's upcoming galactic adventure No Man's Sky, which will, its creators Hello Games say, be infinitely large, with every giant rock and ball of gas able to be explored.

Then there's what Riedl thinks of as real-time adaptation of computer games. "This is when the system wants to learn something about the user and then customize something about the map or the game to the user," he explains. "So, for example, if I knew that you were really interested in exploring maps, exploring worlds, maybe you should have a larger, more intricate world. Whereas maybe the next person doesn't want to spend a lot of time wandering around in the wilderness. Then you need a completely different sort of map. Smaller, more linear sort of map."

The underlying processes for this need not be complicated. You could have a small number variables that trigger changes, Riedl suggests, based on the number of times a player leaves the beaten path or how efficiently they dispose of enemies. The algorithms could be based on just the current player's behavior or on how this player's behavior differs in statistically-significant ways from many thousands of other players, rather like how Amazon decides what books to recommend.

"In one piece of work I looked at hundreds and hundreds of users and tried to categorize them based on skill difficulty," Riedl says. "And then I gave different clusters of players different sorts of monsters to fight against because they were better or easier or harder for those particular users."

Riedl and his colleagues have been exploring these kinds of problems in their GameTailor, Game Forge (see the video below), and, to a lesser extent, weQuest projects over a number of years, and they've already solved many of the issues with using computers to automatically generate and modify various parts of a game. But there's still plenty more to do.

"To me what I think is the big missing area in terms of game generation or automatic game design is the storytelling components, which doesn't have this nice physical manifestation that we can work on," Riedl says. "It's more abstract constructs and conceptual sorts of ideas."

Stories in games are often derided for being too derivative, cliched, and hackneyed. They tend to either lack depth or feel tacked on. But stories are nonetheless important to games as without them a world is empty.

Riedl wants to see this get more attention in his field, to have AI that's capable of creating lore and plotlines that gel with the worlds it generates. Near-impenetrable open-ended world-simulation game Dwarf Fortress does this in a simple manner for its obscenely-complicated, fractally-generated worlds (which are represented by ASCII graphics), but its innovations have not yet been generalized to other game genres.

There's a need for progress here, too. Shortly after Facebook bought virtual reality company Oculus last year, Oculus CEO Brendan Iribe announced at the TechCrunch Disrupt conference that the two companies were looking to use future iterations of the tech to make the first massively-multiplayer-online game (MMO) with a billion players.

MMOs are big business, with the likes of World of Warcraft, EVE Online, World of Tanks, and Second Life boasting millions of monthly subscribers hungry for never-ending streams of quests and worlds and other content to dig into. And it's not always feasible to have teams of humans providing that content.

Minecraft proves that we can make very large worlds with algorithms, Riedl notes, but it also shows that "those worlds would be vastly empty without interesting things to push players to do interesting things." The secret is to find a way to generate more stories and all of the elements that go with them.

"Stories are the things that push people to do activity in worlds," Riedl says. "Virtual characters are the things that make the world feel more full. And these are things that have not been completely overlooked, but have not received as much attention as level design [and aspects of game mechanics]."

This is where Riedl wants to see more attention directed, and it's where we'll head next week as part of a broader look at how computer algorithms can generate all kinds of stories – whether it be basic, formulaic "she did this, then that happened" or more complex and layered with abstract concepts that convey a deeper meaning, and whether it be fiction or non-fiction.

If you missed the first entry in this series on creative AI, about how computers are changing the way music is made, you can catch up here.