A new breath-based sensor from researchers at Penn State could soon offer an easy, pain-free, quick way to diagnose diabetes. The sensor was created through a technique that basically toasts a polymer until it turns into porous graphene.

According to the Centers For Disease Control (CDC), out of the 38 million people who have diabetes, about one in five don't even know they have the condition. When it comes to those who have prediabetes, which means the body has a higher-than-normal level of blood sugar, eight in 10 people are unaware, says the agency. So a test to pick up the condition could go a long way toward helping people make lifestyle changes to either treat diabetes or avoid it altogether.

Currently, diabetes tests are typically done through blood tests carried out at doctors' offices or labs. The most common test requires a simple overnight fast, but more involved diagnostics could involve testing over a few days. While there has been work done on a non-invasive test that diagnoses diabetes by measuring glucose in sweat, getting sweaty isn't always appealing to patients and such tests haven't yet come to market.

Seeking to improve upon diabetes testing, the Penn State researchers decided to focus on markers of the disease in the breath, specifically targeting acetone. This chemical is produced by all people as a byproduct of burning fat, but if the presence of acetone on the breath exceeds 1.8 parts per million, say the researchers, it is an indication of diabetes.

“While we have sensors that can detect glucose in sweat, these require that we induce sweat through exercise, chemicals or a sauna, which are not always practical or convenient,” said lead researcher Huanyu "Larry" Cheng. “This sensor only requires that you exhale into a bag, dip the sensor in and wait a few minutes for results.”

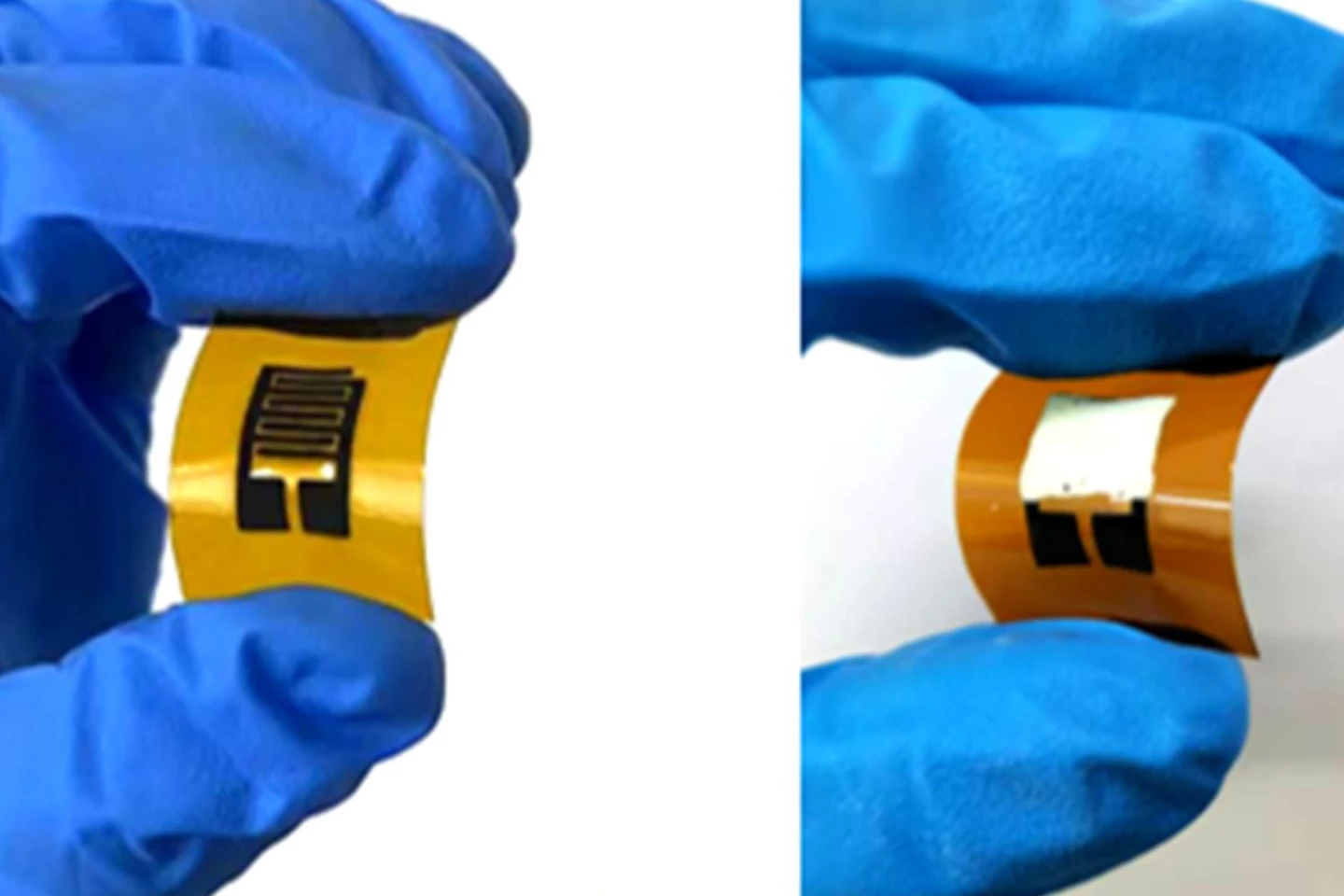

To create the sensor, Cheng and his team used a carbon-dioxide laser to blast a sheet of polyimide film. This converted the material to porous graphene.

“This is similar to toasting bread to carbon black if toasted too long,” Cheng said. “By tuning the laser parameters such as power and speed, we can toast polyimide into few-layered, porous graphene form.”

The idea was that the holes in the graphene are tuned to be the right size to capture molecules of acetone gas. However, by itself the graphene couldn't be made selective enough. So the researchers combined it with a molecular sieve of zinc oxide as well as a membrane that blocks water molecules present in the breath. The result is a thin strip that is extremely sensitive in detecting both diabetes and prediabetes, and fully reusable after a resting period of just 23 seconds.

It does, however, currently require patients to breathe into a bag, which is something the researchers would like to change. They're now trying to find a way to have the sensor sit beneath the nose, or embed it into a mask to make testing even easier. They also say the sensor could be a valuable diagnostic health tool beyond diabetes.

“If we could better understand how acetone levels in the breath change with diet and exercise, in the same way we see fluctuations in glucose levels depending on when and what a person eats, it would be a very exciting opportunity to use this for health applications beyond diagnosing diabetes,” Cheng concluded.

The research has been published in the Chemical Engineering Journal.

Source: Penn State