A common anti-nausea drug used during chemotherapy may do more than ease discomfort, it could help women with aggressive breast cancers live longer, cutting the risk of death by up to 39% in some cases, according to a new study.

Nausea and vomiting are very common side effects of chemotherapy that can significantly affect a person’s quality of life. Thankfully, there are effective medications that can be administered alongside chemo to reduce the risk of this unpleasant side effect.

A new study by Australia’s Monash University and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health (NIPH) has found that using one such medication, aprepitant, during chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer was linked to a decreased risk of cancer spread and a lower risk of future cancer-related death.

“Very little is known about how and why aprepitant use could impact long-term survival outcomes in women with breast cancer, which is why we wanted to examine whether its use at the time of chemotherapy treatment may be linked with survival outcomes in a large population-based cohort of women with early-stage breast cancer,” said Dr Aeson Chang, from the Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences (MIPS).

Aprepitant belongs to a class of drugs called neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) antagonists. It works by blocking the actions of signaling molecules in the brain called substance P neurokinins, which cause nausea and vomiting. It’s been found to be effective in treating acute and delayed nausea and vomiting induced by chemotherapy. Previous studies have implicated substance P and the NK1R system in breast cancer progression.

For the present observational study, the researchers used Norwegian health registry data from 13,811 women diagnosed with invasive early-stage breast cancer between 2008 and 2020, all of whom received chemotherapy and anti-nausea drugs. They specifically looked at distant disease-free survival (DDFS), which is the time until cancer spreads (metastasis) or the patient dies, and breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS), the time until death specifically due to breast cancer. Women were considered to have used aprepitant if they filled at least one prescription for the drug within one year of their cancer diagnosis. Using statistical models, the researchers compared survival outcomes between aprepitant users and non-users, adjusting for factors such as age, cancer stage, cancer subtype, chemotherapy type, and the use of other anti-nausea medications, including ondansetron and dexamethasone.

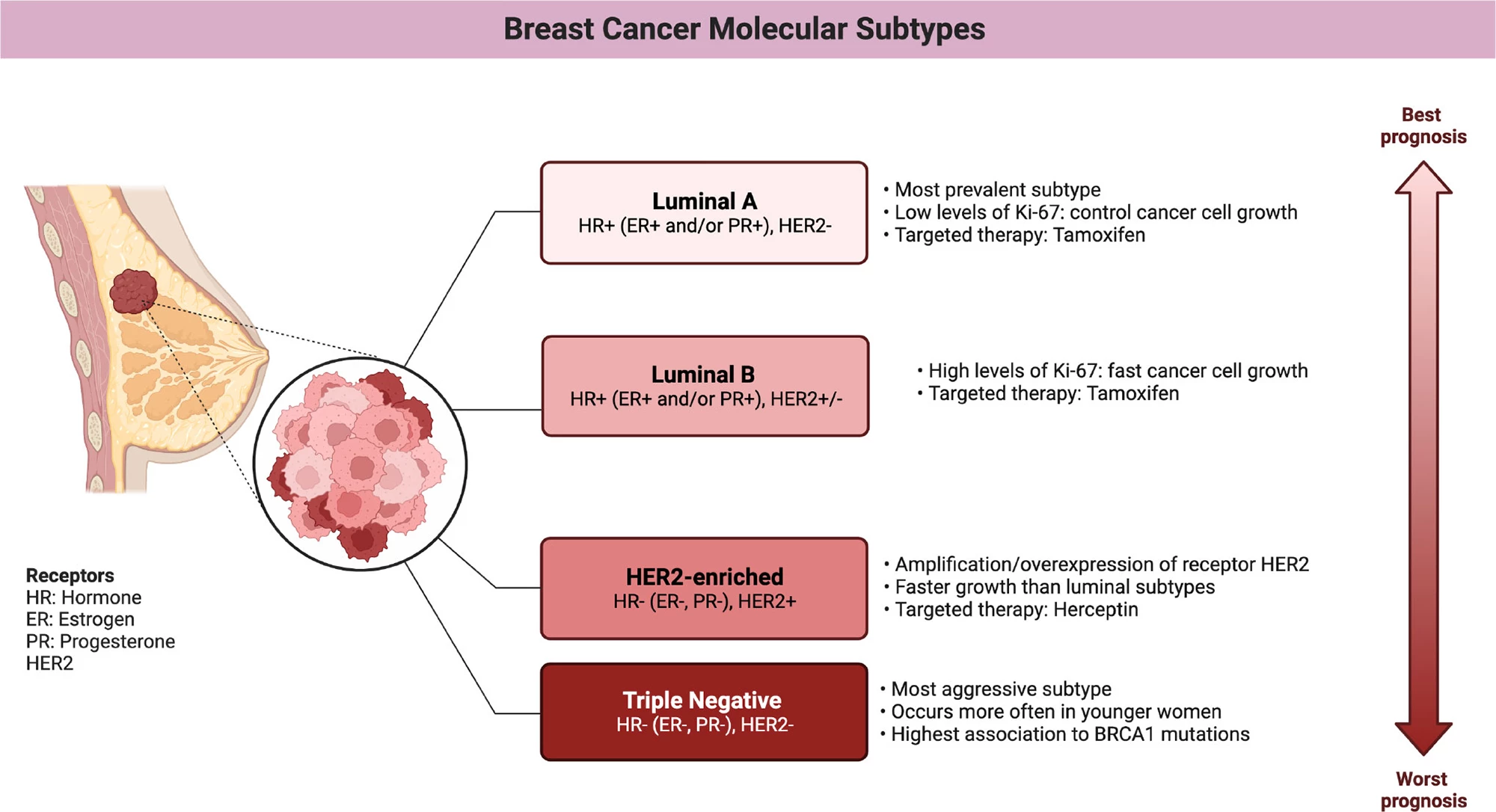

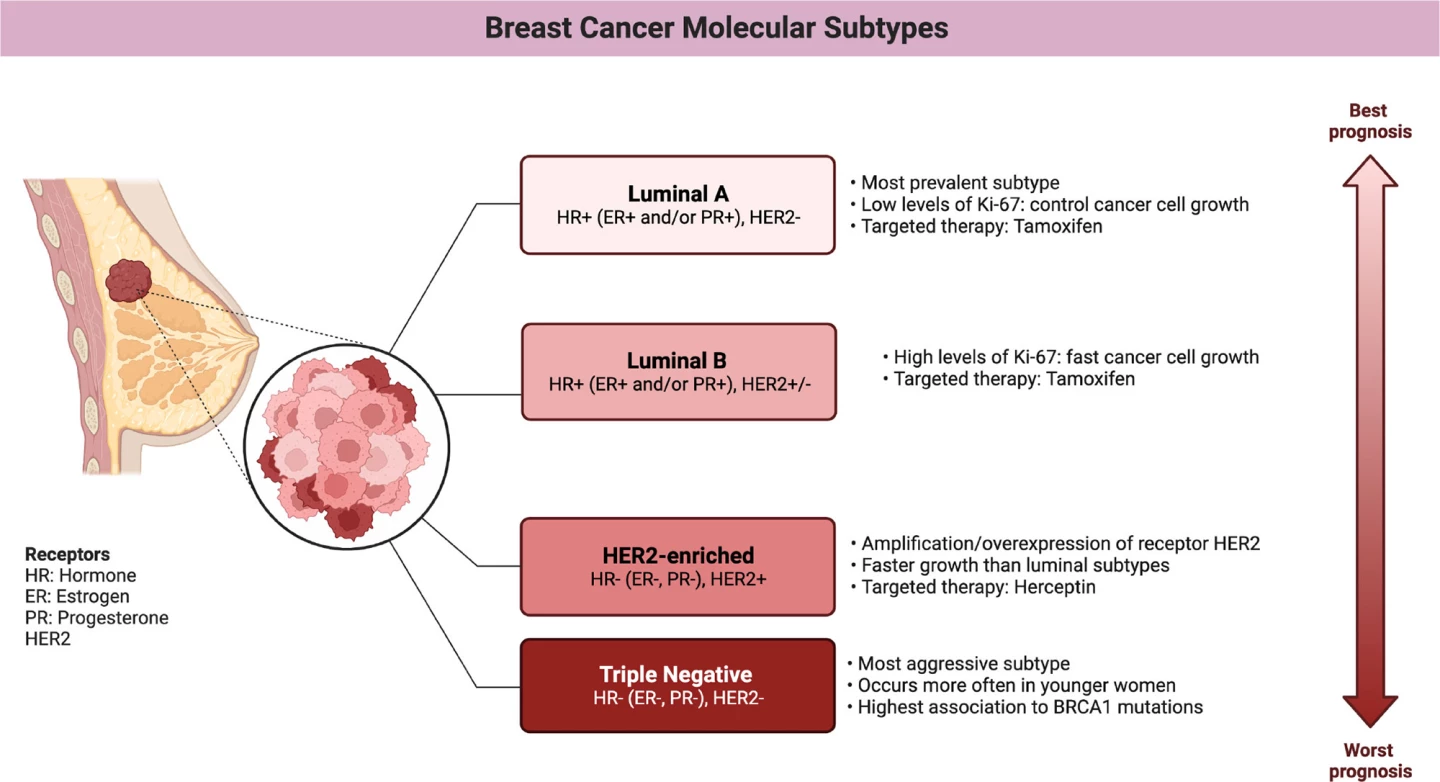

They found that aprepitant use was linked with improved survival, with an estimated 11% lower risk of metastasis or death and a 17% lower risk of death from breast cancer. Non-luminal types of breast cancers, HER2 and, in particular, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) showed the greatest benefit. In women with TNBC, aprepitant use was associated with a 34% reduced risk of metastasis and a 39% lower risk of death from breast cancer.

A quick aside to discuss the different subtypes of breast cancer that are relevant here. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) is a protein that sits on the surface of breast cells, helping to regulate their growth and division. In HER2-positive breast cancer, the cancer cells overexpress this protein, which causes them to grow and divide faster than usual. HER2-positive breast cancers account for around 15% to 20% of all breast cancers. TNBC lacks the three most common receptors found in most breast cancers: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2. Which means that treatments targeting these receptors aren’t effective. Accounting for about 10% to 15% of all breast cancers, it’s an aggressive form that tends to grow and spread faster than other types.

The researchers did not observe a statistically significant survival benefit in hormone-receptor-positive (luminal) breast cancers, subtypes characterized by the presence of ER or PR on the cancer cells. A dose-response trend was observed, with longer aprepitant use associated with more favorable outcomes. Use for 12 days produced an up to 42% reduction in the risk of cancer recurrence or death from breast cancer.

“Generally speaking, when aprepitant is taken it’s during the first three days of chemotherapy treatment,” Chang said. “Given the association between aprepitant and improved cancer outcomes uncovered in this study, it has led us to wonder if even greater survival would be observed if longer-term use of aprepitant was factored into the patient’s dosing schedule.”

There were limitations with the study. Aprepitant users were more likely to receive intensive chemotherapy regimens. Although the statistical models used adjusted for this, residual confounding may still exist. Filling a prescription for aprepitant doesn’t guarantee the drug was actually taken. Survival was only tracked starting one year after diagnosis, which excludes early deaths and might slightly bias results. Some non-users of aprepitant used a related NK1R antagonist, potentially diluting the effect observed. Being an observational study lacking randomized assignment into treatment groups, the study can’t prove cause and effect.

Nonetheless, if its effects are confirmed in randomized trials, aprepitant could be repurposed as a cancer therapy, not just for nausea prevention but as a co-treatment to improve survival, especially in high-risk subtypes like TNBC. The study has also opened the door to further research into NK1R antagonists and their role in tumor biology.

“Given what this study has uncovered, it’s essential these links are further explored – we now need to better understand why these associations have presented themselves, and from there we can look at what this might mean for prescribing and dosing regimens in the future,” said Dr Edoardo Botteri, the study’s lead author and pharmacoepidemiologist at the Cancer Registry of Norway, within the NIPH.

The study was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

Source: Monash University