Scientists have discovered a brain circuit that gives pain its emotional sting, explaining why some hurts linger as suffering. The breakthrough challenges our beliefs about how we process pain and may transform chronic pain treatments.

Pain has several key components, but two of the main ones are the sensory and the affective. The sensory component refers to the physical sensation of pain, encompassing its intensity, location, quality, and duration, whereas the affective aspect encompasses the emotional side of pain, including the unpleasantness associated with it, such as suffering and the desire to alleviate it.

New research from the Salk Institute has identified a specific brain circuit in mice that transforms the physical sensation of pain into emotional suffering.

“For decades, the prevailing view was that the brain processes sensory and emotional aspects of pain through separate pathways,” said Sung Han, PhD, associate professor at Salk and the study’s corresponding author. “But there’s been debate about whether the sensory pain pathway might also contribute to the emotional side of pain. Our study provides strong evidence that a branch of the sensory pain pathway directly mediates the affective experience of pain.”

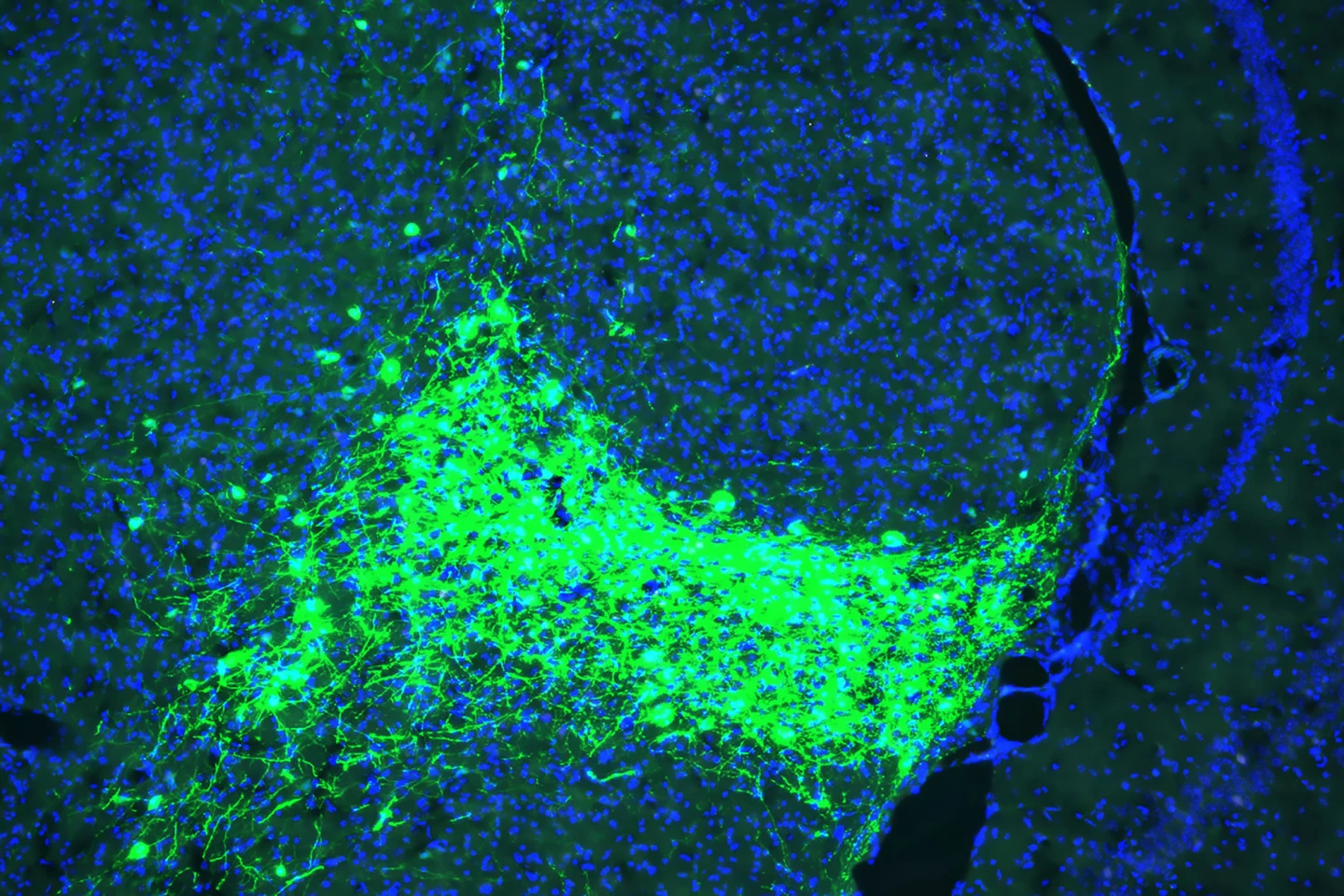

The researchers traced how pain signals move from the spinal cord to the brain in mice. They found that CGRP-expressing neurons in a group of brain cells that form the parvicellular subparafascicular thalamic nucleus (SPFp), in the thalamus, the brain’s central relay station, received pain signals and passed them along to parts of the brain involved in emotions, such as the amygdala. CGRP (calcitonin gene-related peptide) is a neuropeptide, a small protein molecule involved in transmitting pain signals.

When these CGRP neurons were genetically silenced, or switched off, in mice, they still felt pain from, for example, heat and pressure, but didn’t seem emotionally bothered by it or try to avoid it in the future. When the neurons were turned on artificially, the mice reacted with fear and avoidance, even when no pain was actually present.

CGRP-blocking drugs are already used to treat migraines. This study sheds light on why they work, calming not only the pain signals but also the emotional response that turns pain into distress. Conditions such as fibromyalgia, migraines, and chronic back pain often involve emotional suffering that can be more debilitating than the physical sensation. This study identifies a target, CGRP neurons in the SPF, for therapies that could turn down the emotional “volume” of pain without affecting basic pain perception.

“Pain processing is not just about nerves detecting pain; it’s about the brain deciding how much pain matters,” said lead author and Salk neuroscientist, Sukjae Kang. “Understanding the biology behind these two distinct processes will help us find treatments for the kinds of pain that don’t respond to traditional drugs.”

Because the researchers have identified a pathway that also connects to emotional centers in the brain, like the amygdala, it may also be involved in threat sensitivity and fear, hallmarks of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Quieting this pathway might help reduce the emotional suffering associated with trauma.

This research also opens the door to future research into how this pathway may influence emotional pain from social experiences like grief, loneliness, and heartbreak.

“Our discovery of the CGRP affective pain pathway gives us a molecular and circuit-level explanation for the difference between detecting physical pain and suffering from it,” Han said. “We’re excited to continue exploring this pathway and enabling future therapies that can reduce this suffering.”

The study was published in the journal PNAS.

Source: Salk Institute