People with severe chronic pain were far more likely to have elevated levels of eosinophils, a type of white blood cell, a new study found, hinting at an immune link to pain – but the rise in these inflammatory cells didn’t make treatments any less effective.

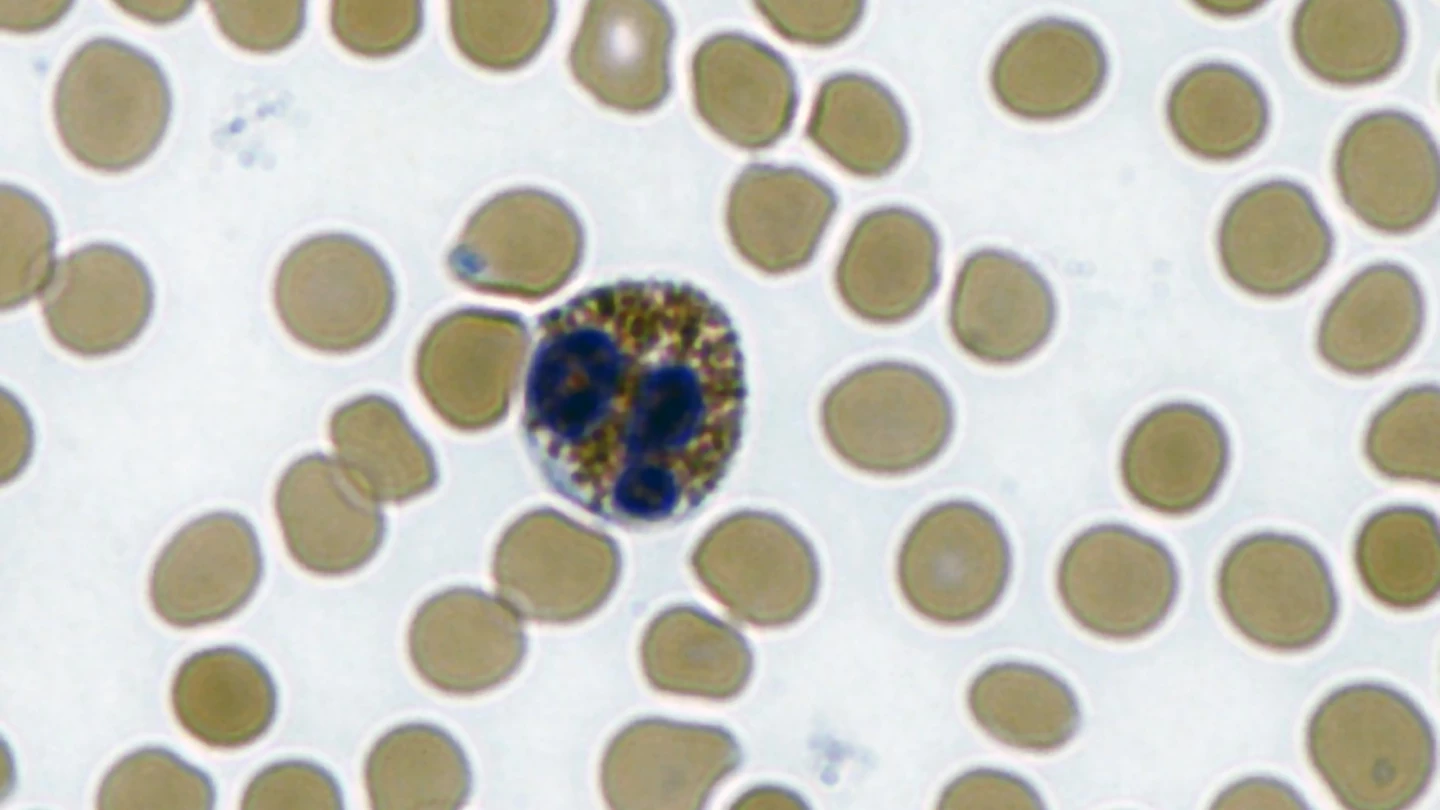

Eosinophils are a type of white blood cell involved in inflammation and allergy. While some diseases, like seasonal allergies, asthma, and autoimmune diseases, are known to cause eosinophilia, or an abnormally high number of these cells, the role of eosinophilia in chronic pain hasn’t been well explored.

A new study by Florida Atlantic University (FAU) and the University of Arizona (U of A) set out to investigate whether people with severe, treatment-resistant chronic pain – the kind that requires spinal cord stimulation or drug pumps – were more likely to have eosinophilia, and whether that affected their outcomes.

“Few studies have examined a connection between eosinophilia and pain,” said Julie Pilitsis, MD, PhD, chair of the Department of Neurosurgery at U of A’s College of Medicine and the study’s corresponding author. “We’re always looking for risk factors to identify and modify – and which ideally could help us predict who will respond to chronic pain treatment.”

In this retrospective review, the researchers examined the past medical records of 114 chronic pain patients who had spinal cord stimulation (SCS) or intrathecal pain pump (ITP) implants. In SCS, an implanted device sends mild electrical pulses to the spinal cord to interrupt pain signals from reaching the brain. It’s often used when other treatments have failed. An ITP is a surgically implanted device that delivers pain medication directly to the fluid surrounding the spinal cord, either continuously or intermittently.

Patients with and without eosinophilia were compared, with eosinophilia defined as ≥350 eosinophils per microliter of blood – a mild threshold, slightly lower than the standard 500 eosinophils per microliter. In addition to eosinophil counts, the researchers measured white blood cells, inflammation markers, pain intensity, complications and comorbidities (conditions such as asthma, migraine, fibromyalgia, and rheumatoid arthritis).

They found that 12.3% of patients had eosinophilia, which is about 10 to 12 times higher than in the general population (<1%). These patients had a mean eosinophil count of 547 cells/microliter, versus 138 in others. No significant differences were observed in age, sex, pain diagnosis, or implant type.

“The condition typically affects fewer than 1 in 100 people, and we found 14 of 114, or roughly 12%, in this group had eosinophilia before treatment,” Pilitsis said. “Now we’re asking what is it about eosinophilia that might predispose someone to chronic pain? Should we be looking at this as a biomarker before and after treatment to see if the latter reduces the eosinophilia?”

Eosinophilia didn’t affect the treatment’s effectiveness. Both groups improved similarly after pain treatment, reporting an average pain reduction of about 1.8 points. In terms of patient safety, no short-term complications occurred among the eosinophilic patients, and none needed device revisions or removals. Comorbidities weren’t more common among those patients with eosinophilia.

The study had some limitations. One being that it was retrospective, and looked back at existing records rather than controlling conditions. Additionally, only 14 patients had eosinophilia. In some cases, there was limited data: few had follow-up tests to see if the eosinophilia persisted, and factors like allergies, infections, or medications that can elevate eosinophils weren’t fully assessed.

Nonetheless, the fact that a connection was found could point to tracking eosinophil counts over time to see if they change with pain treatment or predict a response to it.

“We don’t know if this could be a marker to help identify patients who might do better or worse with treatment, and if inflammation plays a role,” said Pilitsis. “Could spinal cord stimulation reduce inflammation at some point?

“It’s just speculation, but for those who don’t do well, we could think of adding an anti-inflammatory to the chronic pain treatment. We still have many questions.”

The study was published in the journal Neuromodulation: Technology at the Neural Interface.

Source: University of Arizona