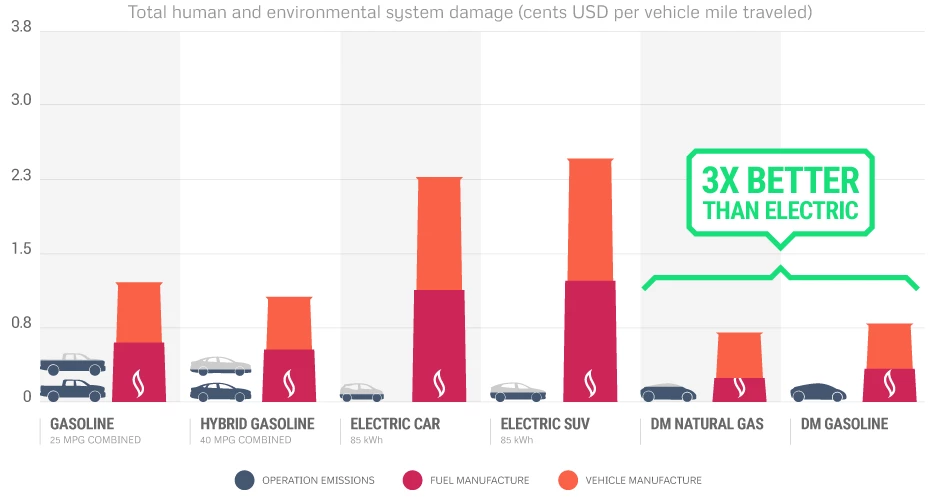

Automobiles have made great strides in recent years in becoming cleaner and greener, but according to Divergent Microfactories, they still have miles to go. The problem, as the company sees it, is that while powertrains have become cleaner thanks to the use of alternative energy sources like battery power and fuel cells, manufacturing is dirtier than ever. The start-up puts forth a solution in the all-new Blade, which it calls "the world's first 3D-printed supercar."

Based in California, Divergent Microfactories was founded by Kevin Czinger, who also founded Coda Automotive. With Coda, he was focused on cleaning up the highways by promoting electric vehicle adoption. Coda's electric car flopped, and the company filed for bankruptcy in 2013, emerging as the newly organized Coda Energy, a company that remains focused on energy storage for commercial and industrial applications.

Czinger has now turned his attention away from the roadways and toward the backend of the industry, working to create a cleaner, more efficient manufacturing paradigm based around 3D printing.

"A far greater percentage of a car's total emissions come from the materials and energy required to manufacture it," he explained during a keynote speech at last month's O'Reilly Solid Conference. "How we make cars is actually a much bigger problem than how we fuel our cars."

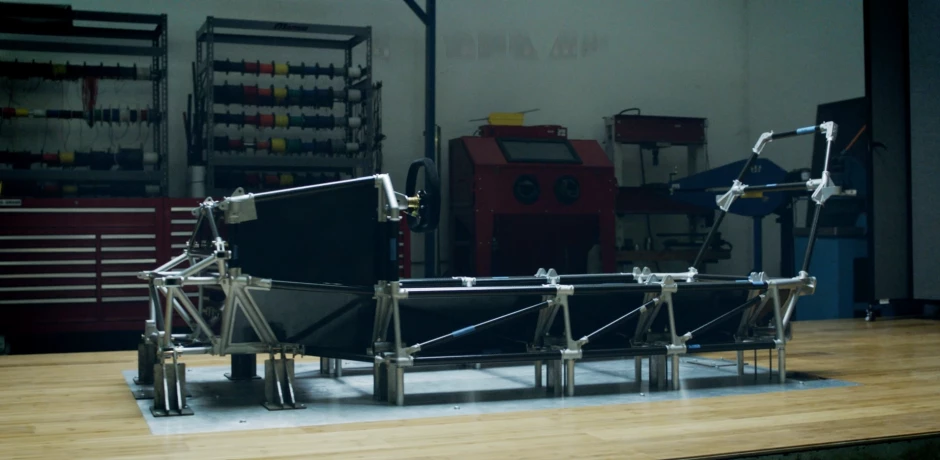

With visions of the hot rod building he did when he was younger, Czinger began formulating a simpler, less centralized concept of auto manufacturing based around a 3D-printed aluminum chassis joint he calls a node. The node is made by melting aluminum powder into form using a laser-based printing system. Individual nodes hold structural carbon fiber tubes together, building up a modular chassis like a sort of upsized children's building kit.

Divergent says that its node-based chassis weighs some 90 percent less than an average car chassis and requires far less material and energy to produce. In fact, in introducing the concept, it carried the nodes and tubes for an entire chassis in a 120-liter (31.7 US gal) shoulder bag.

Divergent believes its 3D-printed nodes are analogous to the Arduinos that have opened up innovation within electronics, hiding technological complexity within an interface that is easy to work with. By using 3D-printed nodes, Divergent says that it can drastically cut down on the amount of space, time and investment required for automotive manufacturing. Once printed, the nodes allow a chassis to be constructed in a matter of minutes in a small, simple microfactory space. No longer will building a profitable car require the resources of a global corporation.

Divergent's plan comes at a time when 3D printing is already starting to infiltrate the auto industry. Last year, Local Motors live-printed what it called the world's first 3D-printed car, an open top composite tub called the Strati. At the time, Local Motors explained that while the older Urbee 3D-printed car was limited to printed panels and parts, the Strati's entire non-mechanical structure was a 3D print. In less than a year since then, we've also seen a 3D-printed German microcar, Shelby Cobra replica and semi-solar electric car.

Those other 3D prints are all fairly tiny cars built primarily around small, limited-power electric drives. Divergent went a little bigger in its launch car, giving the Blade the chops to claim the title of world's first 3D-printed supercar. The car has a 700-hp (522-kW) bi-fuel (gas/CNG) four-cylinder turbo engine and purportedly has the ability to sprint from 0 to 60 mph (96.5 km/h) in a flat two seconds. That's clear "we'll believe it when we see it" territory, but suffice it to say, the Blade takes 3D-printed performance far beyond other contemporary 3D-printed cars.

The Blade chassis weighs just 102 lb (46 kg), and the entire car, complete with composite body and 700-hp engine, is listed at just 1,388 lb (635 kg). That gives it a 1.1 hp/kg power-to-weight ratio in line with the Koenigsegg One:1 and Hennessey Venom F5. We're not entirely optimistic that those numbers will make it to production completely intact, but they sure do look good in a company launch media kit.

Beyond just building the Blade, Divergent hopes to "dematerialize and democratize" the auto manufacturing industry by putting its 3D-printed build technology into the hands of small start-ups. This will allow those start-ups to avoid the extremely cost-intensive barriers of traditional auto manufacturing and innovate new vehicles out of microfactories of their own. Divergent estimates the cost of developing a traditional car factory at US$1 billion, putting the cost of a microfactory with 10,000-car/year capacity at around $20 million.

Divergent says that its node-based chassis ecosystem could just as easily be used to build a pickup truck as a sports coupe. It's not hard to imagine those hypothetical start-ups using the simplified building-block chassis method to quickly design vehicles of all different sizes and styles.

"We’ve found a way to make automobiles that holds the promise of radically reducing the resource use and pollution generated by manufacturing," Czinger says. "It also holds the promise of making large-scale car manufacturing affordable for small teams of innovators. And as Blade proves, we’ve done it without sacrificing style or substance."

If the idea of an auto microfactory sounds familiar, it's because the same Local Motors that laid claim to building the first 3D-printed chassis last year has been using the concept for years. Local Motors microfactories build small, niche vehicles like the Rally Fighter and Verrado trike.

Before Divergent's utopian industry shift happens, the company has some serious work to do. It will need to prove that its construction methods are up to the task of meeting rigid automotive safety standards. It will also need to prove that its microfactory concept is capable of spitting out cars as efficiently and cheaply as claimed. Given that its announcement media kit doesn't include a timeframe or Blade pricing, we're filing both the supercar and the democratization of auto manufacturing at large under "bold ideas we hope to hear more about in the future."

Watch a Divergent chassis come to life in the video below, and if you're interested in hearing Divergent's mission laid out by Czinger himself, check out his 14-minute keynote speech on YouTube.

Source: Divergent Microfactories