This remarkable miniature rotorcraft is so lightweight and efficient that it can lift its own mass given nothing but sunlight. The entire thing weighs about as much as four paperclips, and it can fly all day if the sun's shining.

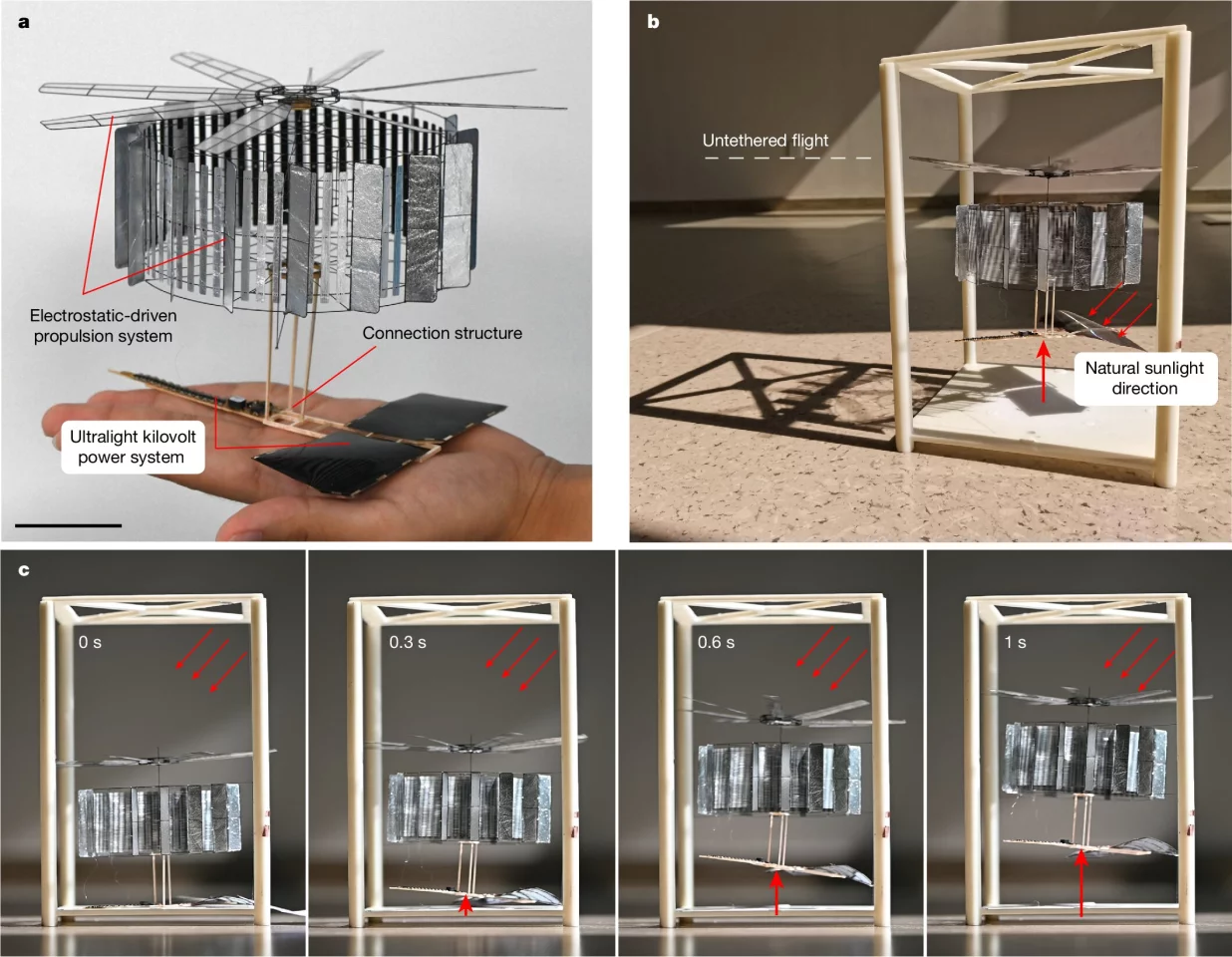

Researchers at China's Beihang University and the Center of Advanced Aero-Engine, have unveiled CouloumbFly, a palm-sized miniature rotorcraft that weighs just 4.21 g (0.15 oz) – yet still boasts a rotor diameter of 20 cm (7.9 in), making it around 600 times lighter than any other comparable small solar-powered drone.

In tethered testing under natural sunlight conditions, CouloumbFly got itself airborne within a second and managed an hour of flight without power diminishing, before a mechanical failure brought it back down. Not much of a big deal if it was a glide-capable winged drone – but this is a miniature helicopter that's entirely responsible for generating its own lift, and managing that on solar energy alone is an extraordinary feat.

The key to its remarkable VTOL endurance is the propulsion system: an insanely lightweight, stripped-back electric motor weighing just 1.52 g (0.054 oz) that drives the 0.44-g (0.02-oz) top rotor. Effectively, those flappy-looking foil-covered tabs hanging around the outside of the airframe are the positive and negative stator plates of an electrostatic motor, and the rotor is the fence-like series of 64 thinner vertical tabs in behind the stator plates.

"When a rotor blade contacts a brush of an electrode plate, a capacitor between the rotor and the next electrode plate will be formed, mainly determining the amount of charge the rotor blade can transfer each time," the researchers explained. "The charged rotor blade is subjected to electrostatic force in the electric field and moves towards the next electrode plate. When the rotor blade passes through the next electrode plate, charge exchange occurs, and the polarity of the rotor blade and the direction of the electrostatic field change simultaneously, which ensures that the driving torque on the whole rotor remains consistent for continuous rotation of the electrostatic motor."

These kinds of electrostatic motors, which harness electrostatic fields instead of magnetic fields for motion, are more often seen used as sensors in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS). But they're perfect in this application, since they jettison all the weight of magnetic coils and rotors.

Beyond the top rotor and the electrostatic motor, there's precious little else to it. The base of the drone holds two whisper-thin solar panels, each maybe an inch and a half (4 cm) square. These generate about 4.5 volts under sunlight, which is fed through a 12-stage voltage multiplier and transformer – which you can see balancing out the solar panels – to step that 4.5 V up closer to 9,000 V, which is then sent into the stator panels. The rest of it's basically just toothpick-thin frame rods and a shaft for the top rotor to sit on.

"In the experiment, we conducted a durability test on the vehicle for one hour, and the vehicle remained in sustained flight throughout the test," said the researchers. "The subsequent experimental results show that the electrostatic motor can still work normally, and the performance remains stable after one hour of continuous operation. This experiment demonstrates electrostatic motors’ excellent stability and durability, providing a foundation for the future development of long-endurance MAVs."

While still in the early stages of development, the aircraft could ultimately be used for different kinds of sustained surveillance, communications and search-and-rescue operations.

Mind you, it'll need some upgrades – not least among which is some sort of flight control system. The researchers now hope to increase the tiny drone's payload, in order for it to be able to be equipped with small sensors and controllers (at present, it could only accommodate around 1.59 g (0.056 oz) of additional payload). What's more, the drones would essentially be so small they'd be difficult to see or track with current technology.

However, the researchers admit there is some way to go, with the technology facing limitations with sunlight availability and humidity.

"In the future, the vehicle can be powered by a combination of rechargeable batteries and solar cells, potentially enabling 24-hour flying operations," the engineers noted. "This solution can also enhance the environmental adaptability of the vehicle, allowing it to maintain flight in low-light-intensity or even no-light conditions."

The research was published in the journal Nature.

Source: Beihang University via Tech Xplore