The Ducati Factory is a must-see petrolhead destination in Italy's "motor valley" alongside the Ferrari, Maserati and Lamborghini factories in Borgo Panigale.

We're here to check out the production of the 1199 Panigale superbike from start to finish, as well as learn about some of the techniques Ducati has used to vastly improve its efficiency, output and reliability.

Our guide today, Livio Lodi, has worked in the Ducati Factory for more than 26 years, in several different departments – which makes him wonderfully qualified to be the brand's official historian and curator of the Ducati museum on site.

"The factory can produce from 60 to a maximum of 300 motorcycles per day. It's depending on the weather – when it's raining or snowing, nobody wants to ride a motorcycle. Also remember we export 90 percent of the total amount of motorcycles we produce. Last year we produced 34,000 motorcycles.

"We produce three different kinds of engine and six different brand families for our motorcycles, with three production lines for the engines, and four production lines for the motorcycles. The production of Ducati is made using the lean production system, or ‘just in time.’ We have outsourced a number of things we used to do in the past, like casting, molding, painting, and some other pre-assembled parts. We can tell you that we estimate that we outsource 90 percent of the painting that we make for the production. But for us, it's not relevant painting the frame or the fairing here."

We start in the "supermarket" area of the factory, a new addition since Ducati radically overhauled its production philosophy in 1997. Individual models each have their own "supermarket" area where manufacturing trays are loaded up with exactly the right parts for each step of the manufacturing process. If there's a bolt left in the tray when a worker has finished at his station, something has gone wrong.

"We have in this factory 1100 workers, including the people that work for the subsidiaries. There are 200 persons in this factory that are just in the racing department.

"The production for just in time is made with two operations for the engine. First, we build the main body of the engine, and then we complete the assembly on the main production line with boxes that contain, in kind of a scale kit model, all the parts that we need for an engine – it doesn't matter if it's an engine for a Panigale, or a Monster 2-valve engine, or a Hypermotard, Multistrada or Diavel.

"With this new style of just-in-time production, we have been able to reduce over 85 percent of the defects in the final product, and we needed to do that – you know that many years ago the reliability of Ducati was not so good. We decided to start this operation together with Porsche in 1997. Porsche engineers came to us here and explained the way to set up the production in a just-in-time philosophy which they got from Toyota originally.

"We work with a Japanese theory – Kaizen, with German efficiency from Porsche, and with Italian fantasy. It looks like the axis during World War 2 but not so morbid.

"You have to remember that when I was first hired, the factory could only produce a maximum of 20 motorcycles a day, and reliability was not good. Also delivery time – if a customer ordered a Monster, for example, delivery time might be up to nine months after the order was placed. Now in 40, 50 working days the bike is delivered. This is a good step forward for our company, which is 150 times smaller than Honda."

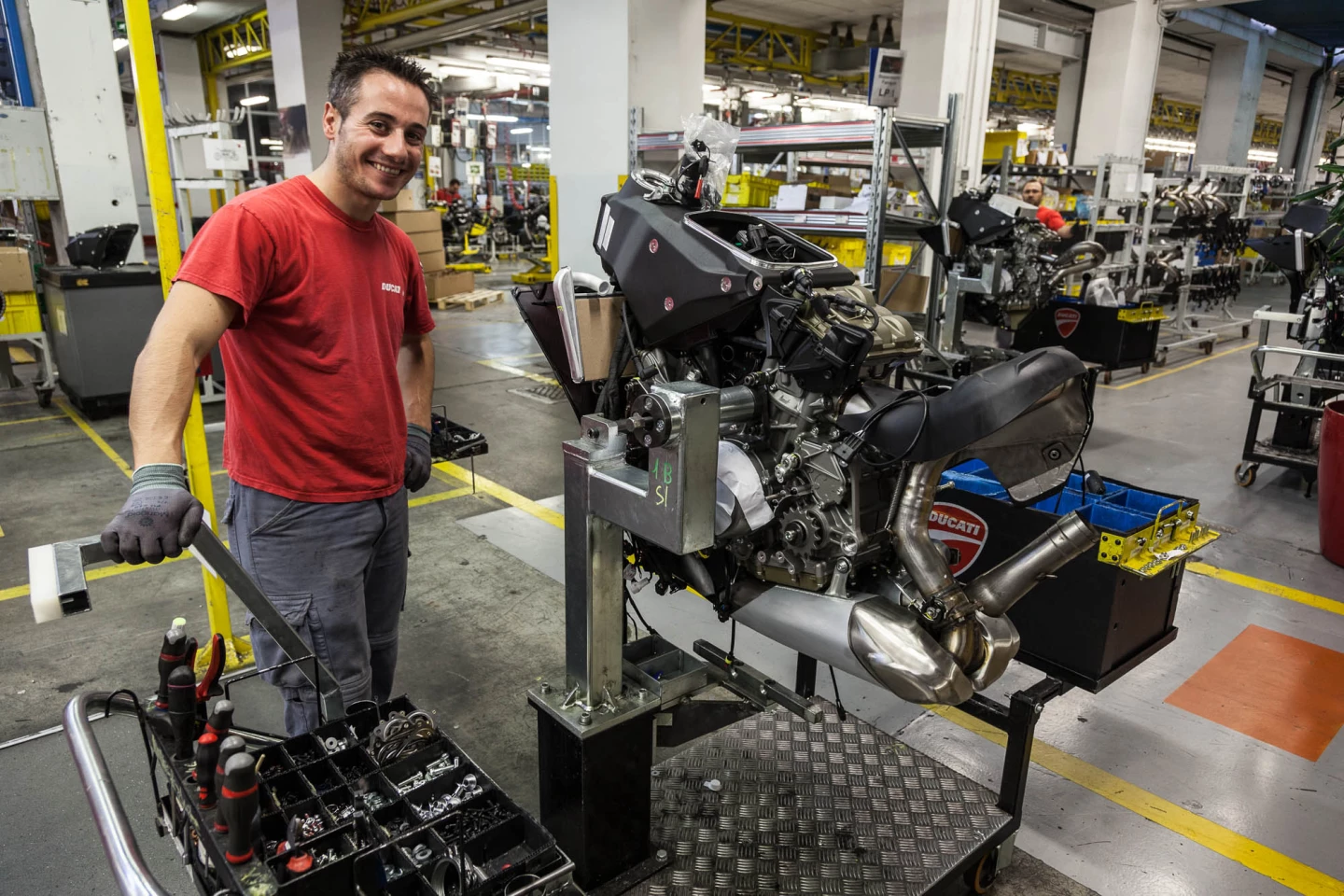

As we move through the engine assembly area, we watch as red-shirted technicians take turns building the engines up from scratch. Computer screens guide the process each step of the way, telling each worker what to grab next from their assembly tray, how to fit it, and what torque the bolts need to be tightened to.

"The red t-shirt that the people who work here wear – it's not a uniform to us. For us it's a matter of pride, you know what I mean? This is the reason why Ducati should be compared like kind of a two-wheeled Ferrari. But there's a big difference – how many Ferrari enthusiasts can afford to buy a Ferrari? If you like Ducati, you can easily buy the cheapest Monster and you are part of the family too.

"The average time for production of one engine is 70 minutes until completion. After the assembly, we have the test of the engine. We take the engine and we make a cold test without petrol. All we are doing here is verifying all the engines we make day by day. The cold test is made just adding some oil inside the engine. Considering that we don't use gasoline, we connect the engine to an electric motor that makes the movement of the pistons, the camshafts and the rocker.

"The engine runs for three minutes at 3000 revs per minute and during the test there are sensors on the engine that monitor the power of the engine with a computer. This test is made for verifying two main things: first the compression of the oil in the head and in the main body, and second, verify the quality of the assembly. We are human, after all; we can make mistakes. If the computer approves the engine, we send it straight to the production line for the motorcycle. In the case that the engine fails the computer test, we dismantle it and reassemble until it passes again."

We move through to the second of three major production areas where engines are first put into their frames. But since we're looking at the 1199 Panigale in production, it doesn't quite work that way.

"This is the production of the Panigale. Here we start to fit the frame together with the radiators and exhausts. For the Panigale, another big step forward is the frame. It doesn't exist anymore, we have this airbox of an aluminum cast part that is a derivation from the carbon fiber frame that we developed in 2009 on the MotoGP series. This is a huge step forward for us.

"Our philosophy is strictly predicated in the racing world. Since the 50s when Fabio Taglioni, the most famous chief engineer, developed the first racing bike, we always shared the technology that we gave the racing bike into the production bike. And why this? Because you know motorcycle riders are dreamers. They wish to be like their favorite hero. How many people have bought a Ducati just because they saw Troy Bayliss or Casey Stoner won with Ducati?"

We then move through to the main assembly line, where bikes are fitted with basically everything else but their fairings.

"The strategy for assembling the motorcycles is equal like for the engine. We have boxes that contain in this case just the smallest parts of the motorcycle. The other sized parts like the wheels or the handlebars or the swingarm are located inside the line so the workers have nothing to do but pick up all the parts to complete one bike.

"The average time for completing one motorcycle is around 90 minutes per each motorcycle. Is average. For a Monster it could be less than 90 minutes, for the Panigale could be a little bit more.

"These are Panigales going to Australia. You know how you can recognize them? From the extra mudguard on the back. I know that several Australian customers used to remove it, but this is illegal."

"When the C.E.O. of Audi came here last year, he said 'we are not changing Ducati. Ducati will stay here in Bologna. We are not pretending to change your way that you produce motorcycles. It is us that must learn, how can you be so accurate and perfect in fixing so many things in such a small space as a motorcycle is, compared with a car.'

"It's a pity with the fairing that you cannot see what is underneath. I think some people like books, they buy a motorcycle because it has a nice cover. Sometimes the makeup is not enough to make something enjoyable. I'd rather see a Panigale without the fairing. It looks like an X-Ray model. Try to imagine how is made the human body from inside. Remove the skin, remove the muscle. That means it's something alive, not just a piece of metal."

Once the bikes are assembled fully without their fairings, it's time for the dyno test. First, the rear wheel is fixed, and the front wheel is manipulated to test the inbuilt speed sensor and ABS components. Then the bike is moved forward and the front wheel is fixed, so the rear wheel speed sensor and traction control electronics can be verified. And then, the engine is fired up – a bike that was just pieces in a box a couple of hours ago now springs to life and its full 200 horsepower are unleashed on the dyno in repeated power tests.

You might choose to run your engine in gently, babying it like the book says, but I can verify that this man has given it an absolute gumboot full and taken it to redline several times before it even went in the crate. Next, dyno complete, it's off to in-house emissions testing.

"When the test is over, the workers come here and they have to check the emission from the exhaust and verifying the injector system. These controls must be done in all the bikes because there is different rules for different countries. Rules are more strict in the US than in other countries. Also like in Australia the famous mudguard you must put on the back. Because if you don't put on these things, you are not allowed to sell the bikes in these countries.

"So when bikes have been verified and approved, we send the bikes straight into this area, where there are yellow crates that we put two bikes in each one and we deliver the bike to the final delivery are that's located in a big warehouse 5 km from the factory. In that place we complete the bike with the fairings, with maintenance books, with toolbox, with the battery.

"If the order comes from Italy or Europe, we need 40-50 days for delivery to the customer. If the order comes from far Europe, Australia or the United States, from 60-70 days because bikes are traveling by sea. This is still a big achievement, because I remember when we produced the first Monster and the first 916 in 1993 and 1994, the average time of delivery was around 9 months to one year. When you received the bike, we had already started producing the new model for the next year. People were very disappointed by this."

"In order to compete with companies like Honda and Yamaha, you need to give a product that could be perfect. But perfection is not of this world, thank God. Even Japanese bikes might have defects. But we could not afford to have a bike that costs more than a Japanese bike that could be full of defects. Now people can perhaps understand why Ducatis cost so much, because the cost of production in Italy is higher than in other countries. But for our customers, who have loved Ducati motorcycles since the 50s, 60s, 70s, they could not imagine a Ducati that is not made here in Italy.

"We show the factory and the museum to everybody. We don't care which kind of motorcycle you have. If you ride a Ducati here, you can leave your bike inside the gates with the parking. If you don't ride a Ducati, you can leave outside the entrance. This is the logical thing. But we don't make motorcycle racism. We show respect to Japanese, like Japanese show respect for us. Because we share the same passion. We know that riding a motorcycle could be enjoyable fun, but also dangerous. The respect that motorcycle riders have between themselves is also made of this thing."

And with that it's out the front gate, where a lonely Suzuki SV1000 is parked, and where a defiant neighbor flies a #46 flag as a constant reminder that for all Ducati's racing success, it still hasn't managed to put together a championship with Italy's greatest rider, Valentino Rossi.

Thanks to Livio Lodi, Silvia Salvatore, David James, Brendan Murphy and Cheng Aleng. There are many more photos in the gallery to check out, get in and have a much more detailed look.