Israeli company BaroMar is preparing to test a clever new angle on grid-level energy storage, which it says will be the cheapest way to stabilize renewable grids over longer time scales. This innovative system lets water do the work.

The zero-carbon energy grid of the future looks remarkably complex. Solar, wind and other renewable energy sources will all contribute power when they can – but this won't match up with demand, so energy storage and release measures will be critical. And these will be needed for a range of different time scales. Some will need to smooth out daily peaks and troughs. Others will operate between days and weeks, filling in when overcast weather makes for a couple of days of poor solar output.

And then there's long-duration storage, which will attempt to stash electrons for the winter, when there'll be a seasonal lull in solar generation that wind might not make up. That's the area BaroMar wishes to address with its interesting take on compressed air energy storage (CAES).

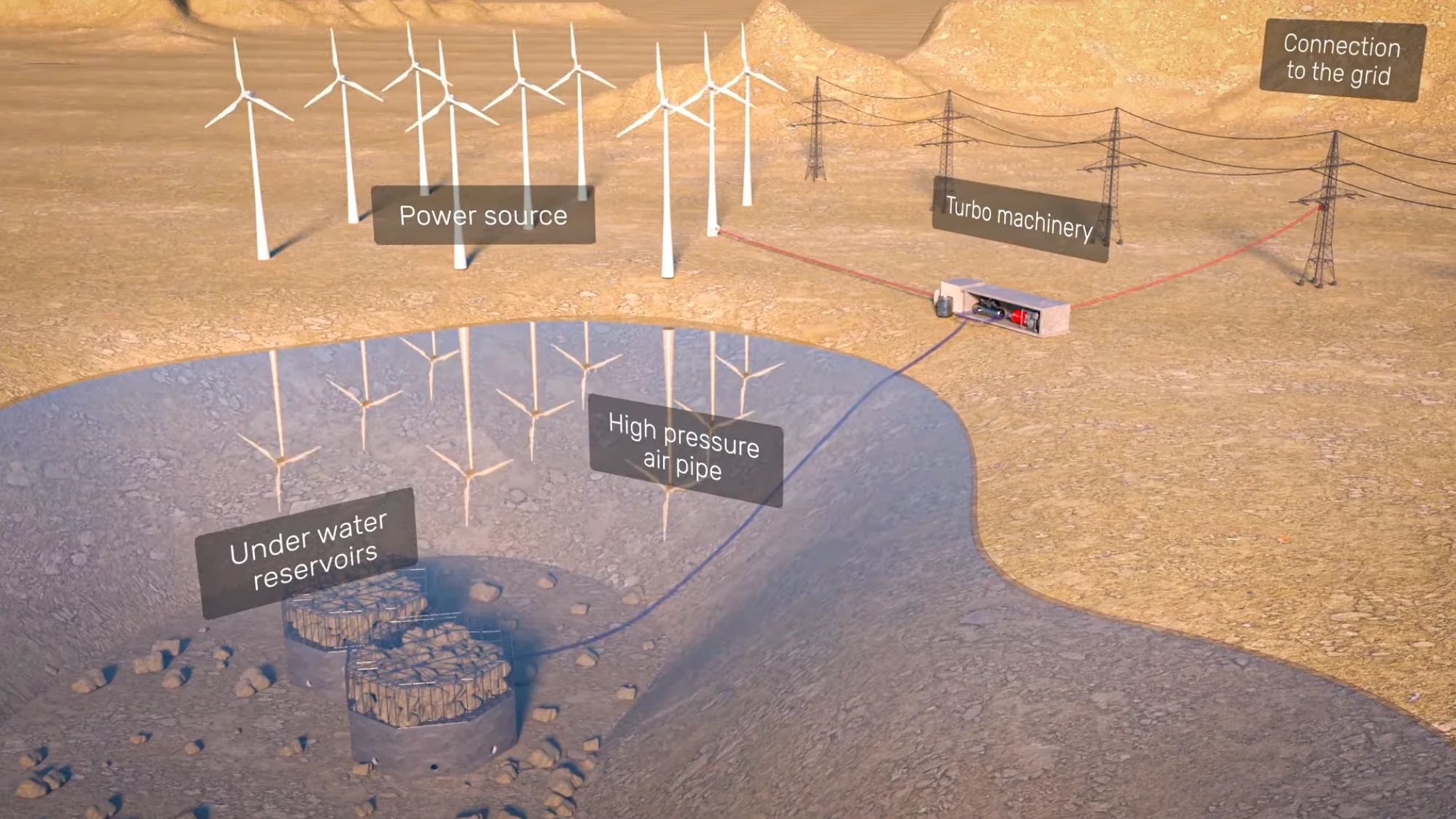

CAES involves using excess energy to run compressors, typically pumping air into large, rigid tanks where it can be stored at high pressures, then released through some kind of turbine that can drive a generator to recover the energy. It's already quite a cost-effective energy storage option – but BaroMar says it can beat traditional systems over long-duration energy storage using an amusingly low-tech solution.

Basically, the company's plants will be stationed near coastlines with access to deep water. And instead of large high-pressure tanks, BaroMar uses the pressure of the water column to store compressed air in much cheaper enclosures.

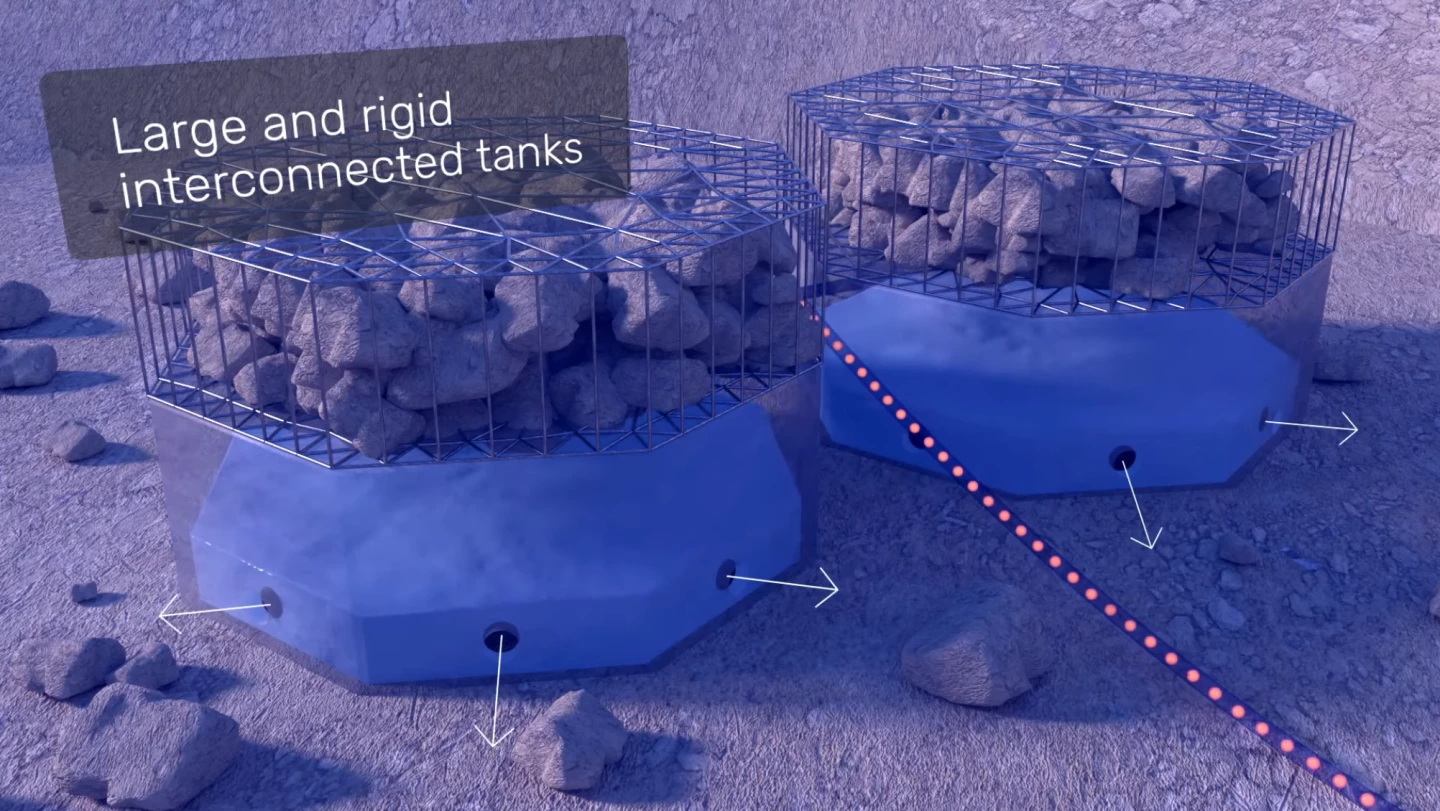

We're talking a series of big, cheap, dumb, concrete and steel tanks with cages full of rocks on top of them, to keep them submerged at between 200-700-meter (650-2,300-ft) depths. These tanks have a number of water-permeable valves around them and start out completely full of seawater. The compressor and generator systems live close by on dry land, and when there's excess energy to be soaked up, the compressor feeds ambient air down to these tanks through long hoses at 20-70 bar (290-1,015 psi), depending on the depth.

The compressed air forces water out of the tanks – but since the hydrostatic pressure of the external water equalises against the internal air pressure, the tanks don't need to be anywhere near as strong or expensive as land-based tanks that need to hold high-pressure internal air against regular atmospheric pressure on the outside.

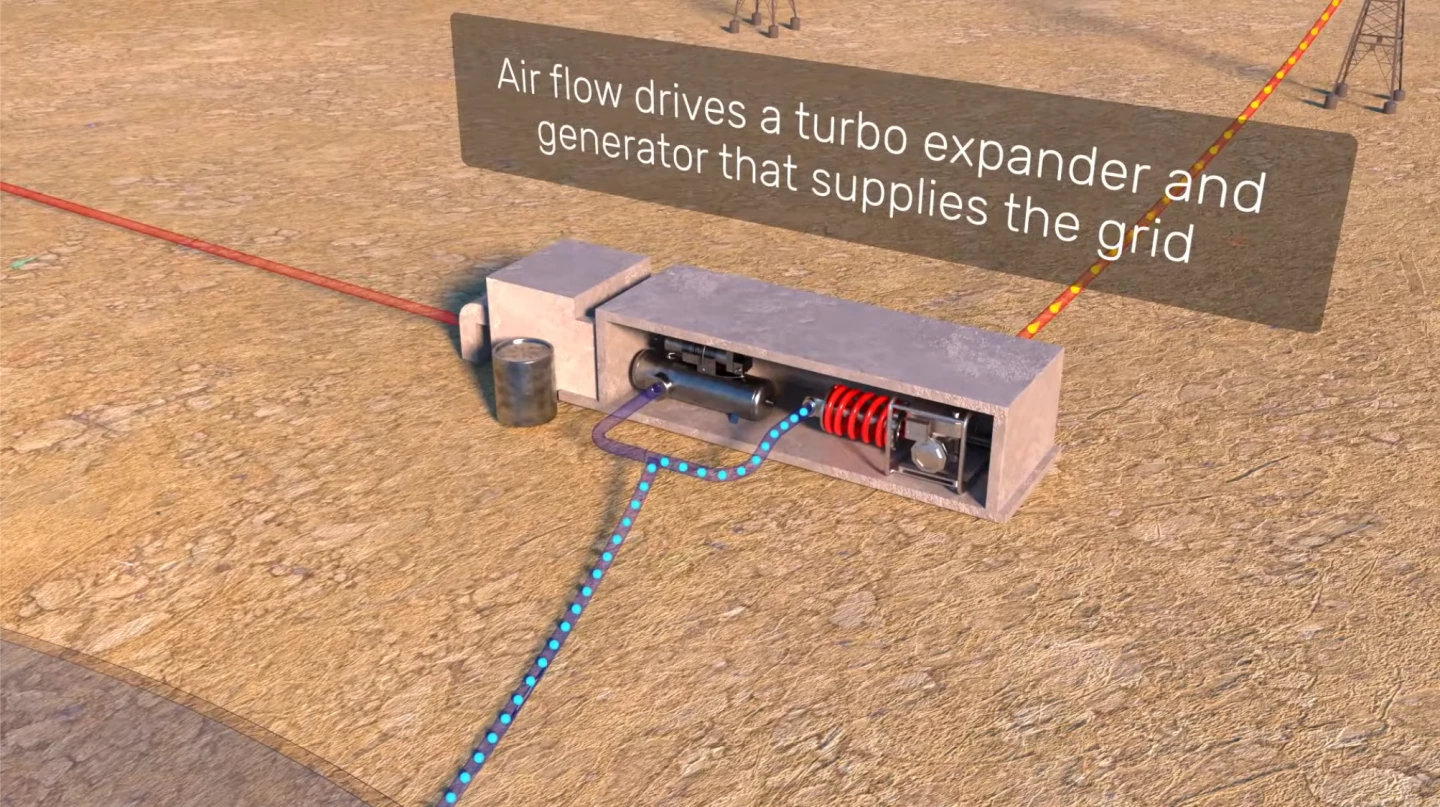

When it's time to recoup the energy, the system allow air to run back up the hose into a thermal recovery system, followed by a turbo-expander that drives a generator. At the other end, water rushes back into the tank, ready to be displaced again when the compressor is running.

According to engineering consultancy Jacobs, which has been appointed to design a pilot project in Cyprus, the target is a round-trip efficiency around 70% – about the same as the world's largest CAES plant (a 100-MW, 400 MW/h installation in Zhangjiakou, northern China), and a very high efficiency compared to traditional compressed air systems. This underwater pilot will, of course, be much more modest, storing just 4 MWh.

BaroMar claims it should beat competing long-duration energy storage (LDES) options on cost, thanks to its long-lasting, very low-cost tanks and low-to-zero underwater maintenance costs. Running a 100 MW/1 GWh installation 350 days per year for 20 years, BaroMar says it can deliver a Levelized Cost of Storage (LCoS) of US$100 per MWh, as compared to "other LDES technologies" which, it claims, come in closer to $131/MWh.

Of course, there are challenges with anything that's designed to operate for 20 years under the sea. Jacobs, tasked with actually designing the thing to a standard that can be built, hints at the hurdles ahead. "This project requires extensive geophysical, geotechnical and bathymetric surveying, investigation, feasibility studying and permitting for tank installation at deep depths for onshore mechanical and electrical equipment needs," said Jacobs Vice President Fiachra Ó Cléirigh in a press release.

Still, the cost-effective and scalable solutions are going to win in the new renewable grids – and if BaroMar's idea does what the company claims, it'll be relevant to plenty of locations, since cities are so often close to the coast. We look forward to hearing more about this project.

Source: BaroMar and Jacobs via CleanTechnica