The Andean condor’s drag-reducing aerodynamic wings have inspired the creation of a winglet, which, when added to a wind turbine blade, boosted energy production by an average of 10%, according to a new study.

With a wingspan of 10 to 12 ft (3 to 3.7 m), the Andean condor is the largest flying bird in the world. Despite a weight of up to 35 lb (16 kg), its wings’ aerodynamics reduce drag, allowing the birds to glide for long distances without flapping, up to 150 miles (241 km) in a day. Researchers from the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Alberta (U of A) in Canada have examined whether attaching a condor-inspired winglet to a wind turbine blade can also reduce drag and increase energy production.

Wind turbine blades use aerodynamics to extract the wind’s energy, which is converted to electricity. But ensuring that they produce as much energy as possible is necessary if we’re to rely on clean, sustainable energy production.

What commonly reduces the efficiency of wind turbines is induced drag, created as a result of lift. As a blade passes through the air, an area of lower air pressure is formed on top of it (the suction side). Higher-pressure air below the blade (the pressure side) seeks equilibrium with the lower-pressure area above, resulting in tip vortices, air that trails off the blade tips in spirals. The vortices deflect airflow downward (downwash), creating induced drag.

While most modern airplanes reduce induced drag by using winglets to minimize the effect of tip vortices, their use in the wind industry is still in its infancy. Studies into wind turbines with winglets have noted a boost in power production but often at the cost of extending the blade tip, making it difficult to ascertain whether the improvement is directly attributable to the winglet or an increase in the blade’s wetted area, the area in contact with external airflow.

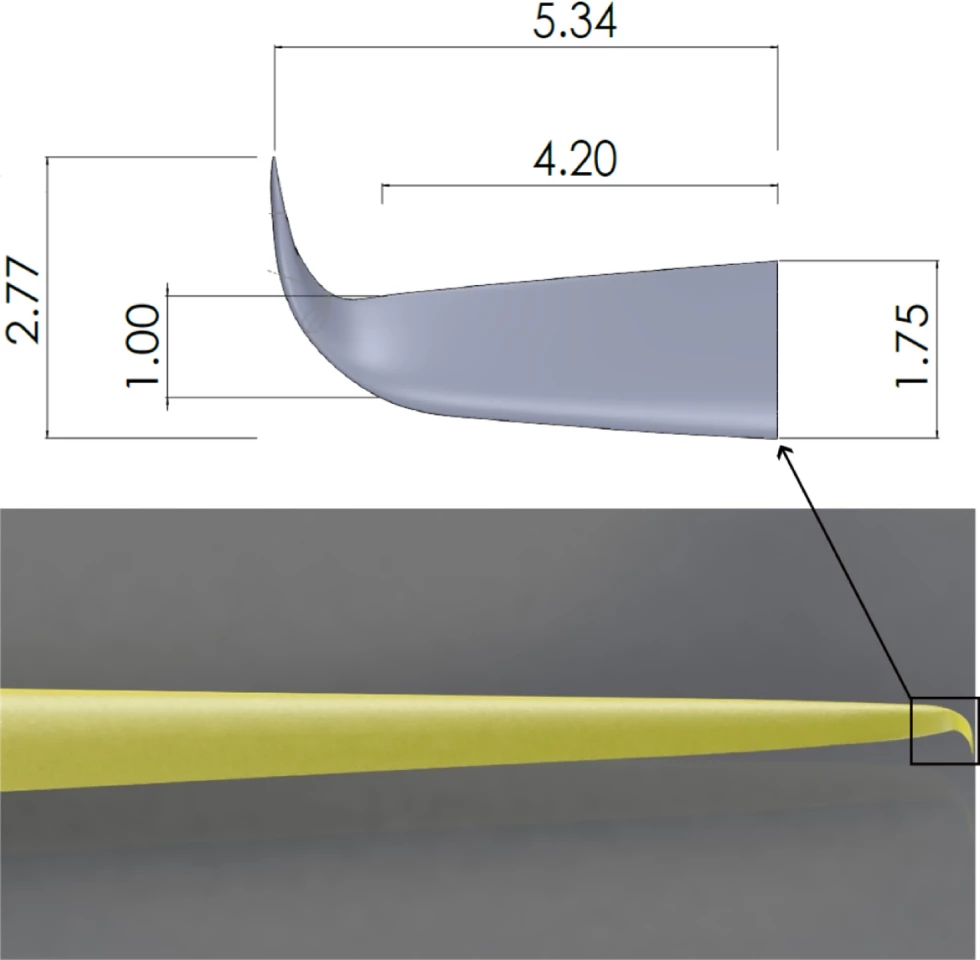

To clarify the issue, the U of A researchers turned to Biome Renewables, a Canadian industrial design firm that creates clean energy products by mimicking nature and has designed winglets based on condor wings. Biome developed its bio-inspired winglet for ‘Project Condor.’ It’s 17.6 ft (5.35 m) long and designed to be retrofitted to a wind turbine’s blade wingtip after production. The researchers used computer simulations to determine the effect that adding the Biome winglet to a sample wind turbine had on its power production.

They found that adding the winglet increased the pressure difference between the suction surface and pressure surface along the blade’s span, which in turn increased the turbine’s torque (rotational force around an axis) and power production. The average increase in energy production was 10%, which the researchers concluded was attributable to the aerodynamic changes caused by the winglet and not just an increase in the blade’s swept area.

“To sum up, the results of the wake study and the power production suggest that this bio-inspired design can increase the power output of the wind turbines,” said the researchers.

The study was published in the journal Energy.

Source: U of A via Recharge News