In many ways, space is the perfect place for a solar energy array. There are no clouds in the way, no seasonal variability, no atmospheric filtering, and your solar panels can operate at peak efficiency around the clock, since the planet doesn't block the Sun. Put a solar panel in space, according to some estimates, and it'll generate 6-8 times more energy than it can down here on Earth.

Getting the power back down to the surface? Now there's the problem. Geosynchronous orbit, in which a satellite stays more or less right above a single point on the Earth, is about 36,000 km (22,500 miles) up in the air. That's nearly three times the width of the Earth, and a bit further than most extension leads can reach. Transmission, plus the hideous expense of space launches, has been the problem.

But space launch costs are coming down with the advent of reusable rockets and alternative launch technologies, and the world is in desperate need of reliable clean energy, so research on space solar continues, particularly focused on improving the efficiency of wireless power transmission, in the hope that we're just a couple of breakthroughs away from commercially competitive extra-terrestrial power generation.

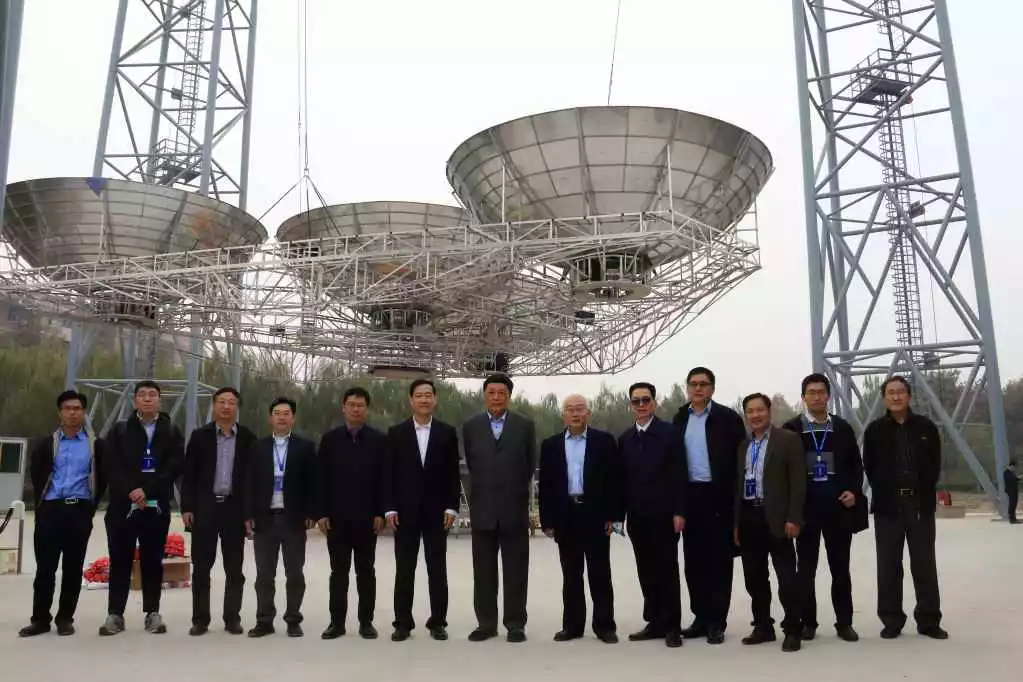

One such research project concerns this "full-link, full-system space solar power ground verification system," built at Xidian University in Xi'an, North-Central China – a former capital of China under many dynasties and a city best known to the Western world as the place where 8,000-odd terra cotta warriors were found in a subterranean chamber back in the 70s.

Under the direction of Duan Baoyan, this 75-m (246-ft)-tall ground verification system, which began construction in 2018, has been designed to enable research into "high-efficiency light concentrating and photoelectric conversion, microwave conversion, microwave emission and waveform optimization, microwave beam pointing measurement and control, microwave reception and rectification, and smart mechanical structure design."

According to a Xidian University press release, the facility has recently been approved by a group of visiting experts after demonstrating wireless microwave transmission of power across a 55-m (180-ft) distance. It's the first system in the world to cover the full range of space solar functions, including tracking the Sun, concentrating light, converting it to electricity, transmitting it in microwave form, and receiving it at a separate rectenna – and the university says it's running successful tests some three years ahead of schedule.

The upper part of the structure suspends an array of dishes that acts as a surrogate satellite, focusing sunlight, converting it to energy and sending it down to the ground, where a rectenna dish collects it.

The research team is under no illusions: getting from 55 m to 36,000 km with high enough efficiency to make space solar worthwhile will "require successive struggles of several generations," according to the press release. It'll be a long time before money spent on this tech bears more fruit than simply building more solar arrays here on the Earth. Indeed, should a space-based energy transmission antenna be deployed, the ground-based rectenna array will most likely need to be several kilometers across in order to receive a useful amount of energy.

In the meanwhile, companies like New Zealand's Emrod are pushing forth on wireless microwave power transmission for applications closer to the Earth, like replacing high-voltage power lines across difficult terrain.

Source: Xidian University