Fervo's "next-generation geothermal" technology has proven itself in testing, becoming the most productive enhanced geothermal plant in history. The company hopes its approach will radically expand access to clean energy, like shale did for oil.

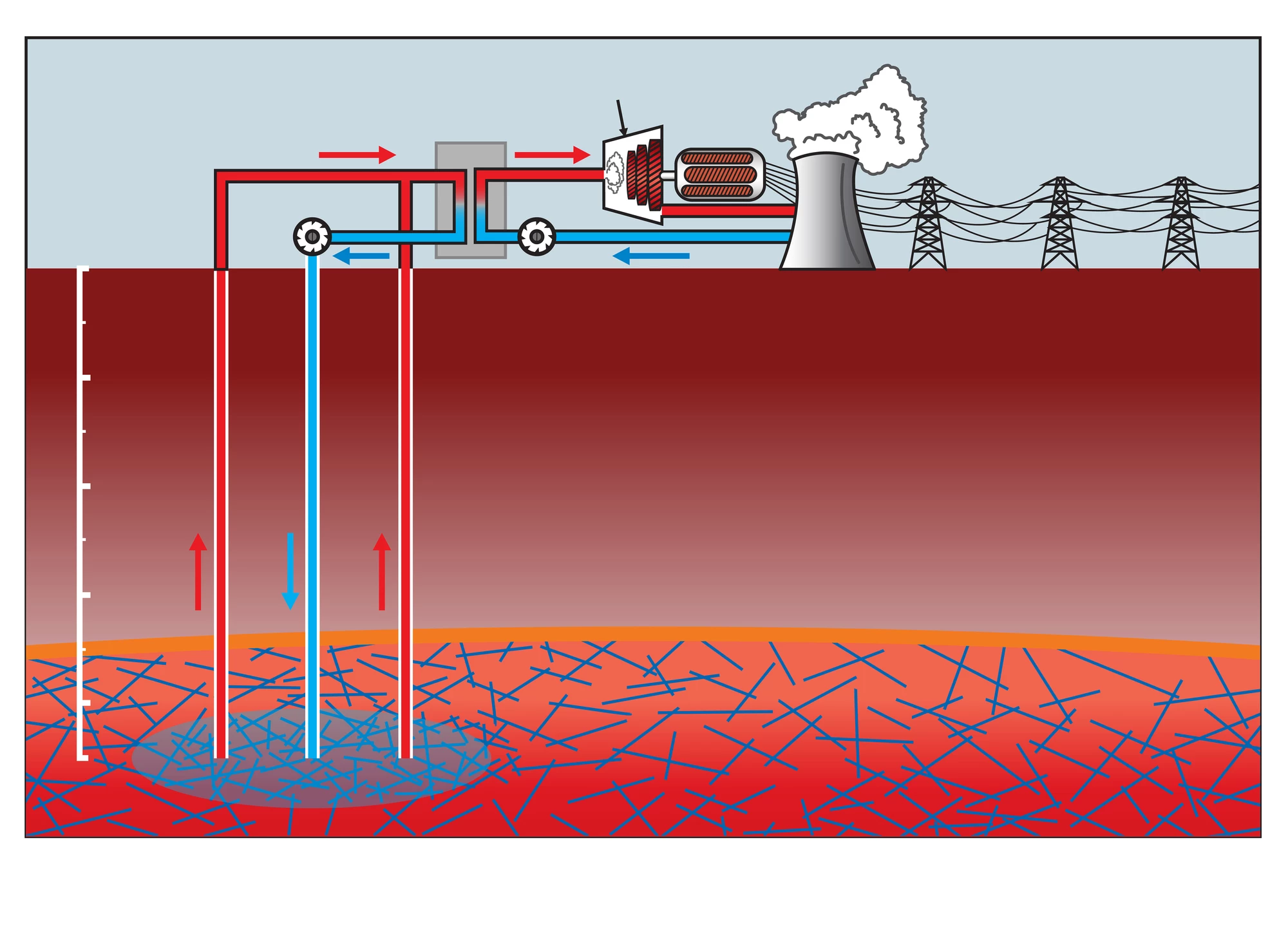

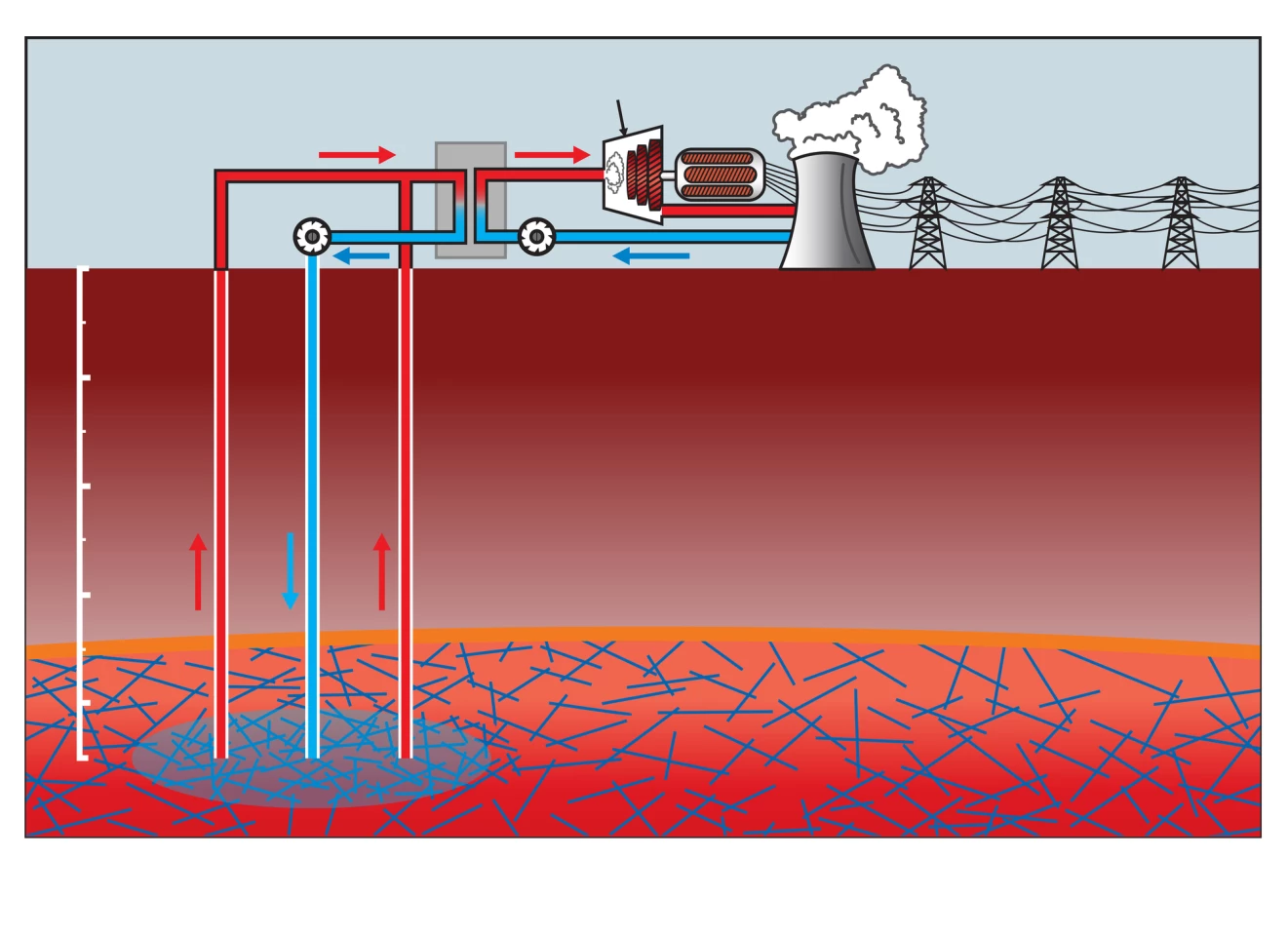

There's a near-unlimited amount of clean energy under our feet, in the form of hot rocks. You can generate clean electricity 24/7 – not intermittently, like solar and wind – if you can get water down into that rock and back to the surface to drive steam turbines. A reliable source like this would make the clean energy transition much smoother.

But as we've written many times before, there are only limited places where geothermal power currently makes economic sense – places like Iceland and New Zealand, for example, where the heat is close to the surface, easily accessible, and the site is close enough to a grid connection to make it worth exploiting.

This, and the fact that some 40% of all geothermal wells don't end up working out, has put the brakes on hot rocks as a power source. According to IRENA, geothermal contributes about half of one percent of global renewable energy, and a vanishingly tiny slice of overall global energy production.

One very exciting way around this has been proposed by Quaise, which plans to re-power old coal-fired stations by drilling deeper into the Earth's crust than ever before using technology from the nascent fusion industry. But this may take some time to come to fruition.

Fervo's solution is a bit more down-to-Earth, as it were, and draws on much more established, high-volume machinery and techniques from oil and gas production. Essentially, Fervo aims to do for geothermal what shale oil and fracking did for hydrocarbons, radically improving access to resources and unlocking energy where previously it was too expensive to get to.

A typical geothermal plant attempts to identify areas of highly fractured, highly permeable and high-temperature rocks, then sinks a vertical water injection bore on one side of this area, and a steam recovery bore on the other, hoping that the water will go through the hot rocks, then be picked up on the other side as steam.

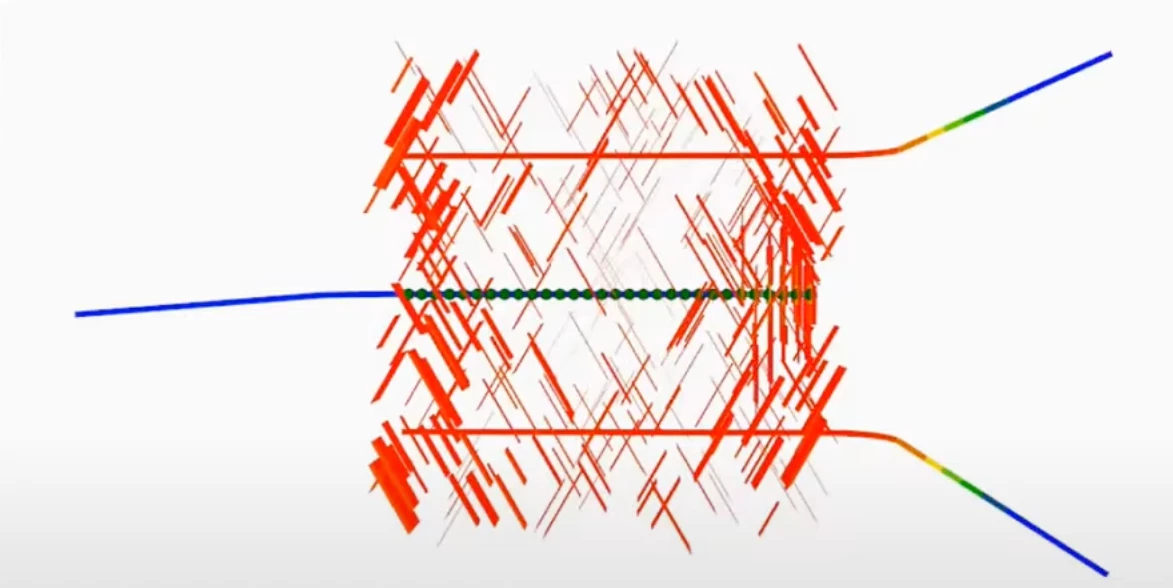

But since this often fails to produce a useful flow of steam, Fervo has developed a technique to take all the guesswork out. It uses horizontal drilling techniques to create long, horizontal channels through the rock, then injects pressurized fluid to fracture the rock, creating large areas of high permeability. This "enhanced geothermal" approach, it says, delivers much more reliable results.

So instead of a vertically drilled geothermal resource with only a small point of contact at either end, Fervo creates enormous, custom-fractured resources, with water pumped in at many points along a pipe that might extend thousands of feet across, and recovered at just as many points though one or more long, horizontal steam recovery pipes.

The result, says the company, is that you get more steam, more power, and a much better chance of striking hot rock gold than with traditional approaches. And that should make geothermal economically viable in a ton more locations – potentially, just about anywhere.

Fervo's first full-scale commercial pilot, Project Red in Nevada, is the first time a geothermal project has ever drilled a horizontal pair of bores, extending some 3,250 ft (990 m) laterally. It has now completed a 30-day well test, producing a flow rate of 63 liters per second, at temperatures up to 191 °C (376 °F). It produces 3.4 megawatts of power, or about enough to power 500 US homes.

“By applying drilling technology from the oil and gas industry, we have proven that we can produce 24/7 carbon-free energy resources in new geographies across the world," said Tim Latimer, Fervo Energy CEO and Co-Founder, in a press release. "The incredible results we share today are the product of many years of dedicated work and commitment from Fervo employees and industry partners, especially Google."

The company's next project will produce twice as much energy, but the end goal here is to get geothermal into the realm of mass manufacturing, where sheer volume can drive down costs on one side and rapid learning can improve results at every stage of the process to drive things down even further.

In a 2020 lecture to students at the Energy Institute, University of Texas at Austin, Latimer spelled out a three-stage commercialization plan, starting out with expanding production at existing geothermal plants to the tune of ~200 megawatts, then graduating to deeper resources adjacent to those existing plants, which could unlock as much as 2 gigawatts of production.

Finally, with some runs on the board, the company believes it'll have driven costs down low enough to explore completely new resources at depths as low as 4.5 km (2.8 miles) below the surface. That could get this tech into the hundreds of gigawatts, and a significant contribution to firming up renewables-based power grids.

The company is well-funded, with some $187 million raised according to Crunchbase. So it's certainly got an opportunity to make a difference. We look forward to learning more about Fervo's progress.

Source: Fervo Energy