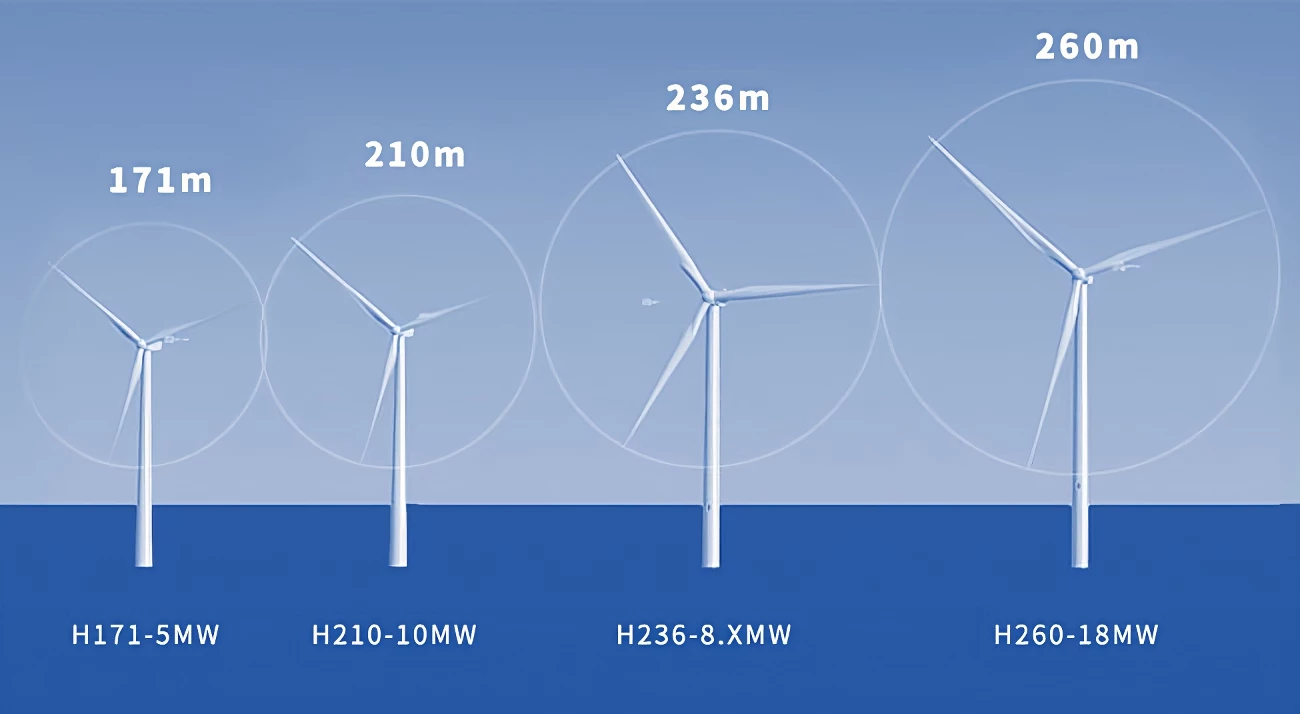

The China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC) is upping the ante on offshore wind, announcing it's building the largest and most powerful wind turbine ever, making a peak 18 megawatts with an enormous 260-meter (853-ft) diameter on its three-bladed rotor.

It makes sense for a shipbuilding enterprise to get involved with this project; the blades of much smaller turbines are already a huge pain to transport, so building them right next to a dock in a facility designed for making, handling and launching enormous structures into the water eliminates a ton of problems as you attempt to go bigger.

Size is paramount when it comes to wind; the longer your blades, the larger the swept area and the more energy you can harvest from a single pole – and when it comes to offshore wind, the sea-bed foundations carry an outsized cost, so being able to generate more from fewer locations is a big deal.

The previous record-holder, the MingYang Smart Energy MySE 16.0-242 uses 118-m (387-ft) blades to sweep a 46,000-sq-m (495,140-sq-ft) area. CSSC Haizhuang's new H260-18MW turbine increases the blade length by 8.5%, to 128 m (420 ft), bumping up the swept area by 15.2% to 53,000 sq m (570,490 sq ft).

In the de facto standard for putting huge areas in some kind of human context, that's a jump from about 8.6 standard NFL football fields' worth of swept area to about 9.9. Under peak conditions, the H260-18MW machine will generate 44.8 kWh of energy every time it spins.

Weirdly, it promises to deliver less power at the end of the day than the smaller MingYang turbine. CSSC says the new size king of offshore wind, "can output more than 74 million kilowatt-hours of clean electricity per year, which can meet the annual electricity consumption of 40,000 households of three," while MingYang says, "a single MySE 16.0-242 turbine can generate 80,000 MWh of electricity every year, enough to power more than 20,000 households." Those sound like some wildly different households.

CSSC says that an example 1-gigawatt capacity offshore wind farm using these 18-MW beasts would require 13% fewer units than if you'd used 16-MW turbines, and the corresponding reduction in sea bed work, cabling and whatnot would reduce the cost of the farm by "hundreds of millions of yuan," with each 100 million yuan representing about US$14.8 million at current exchange rates.

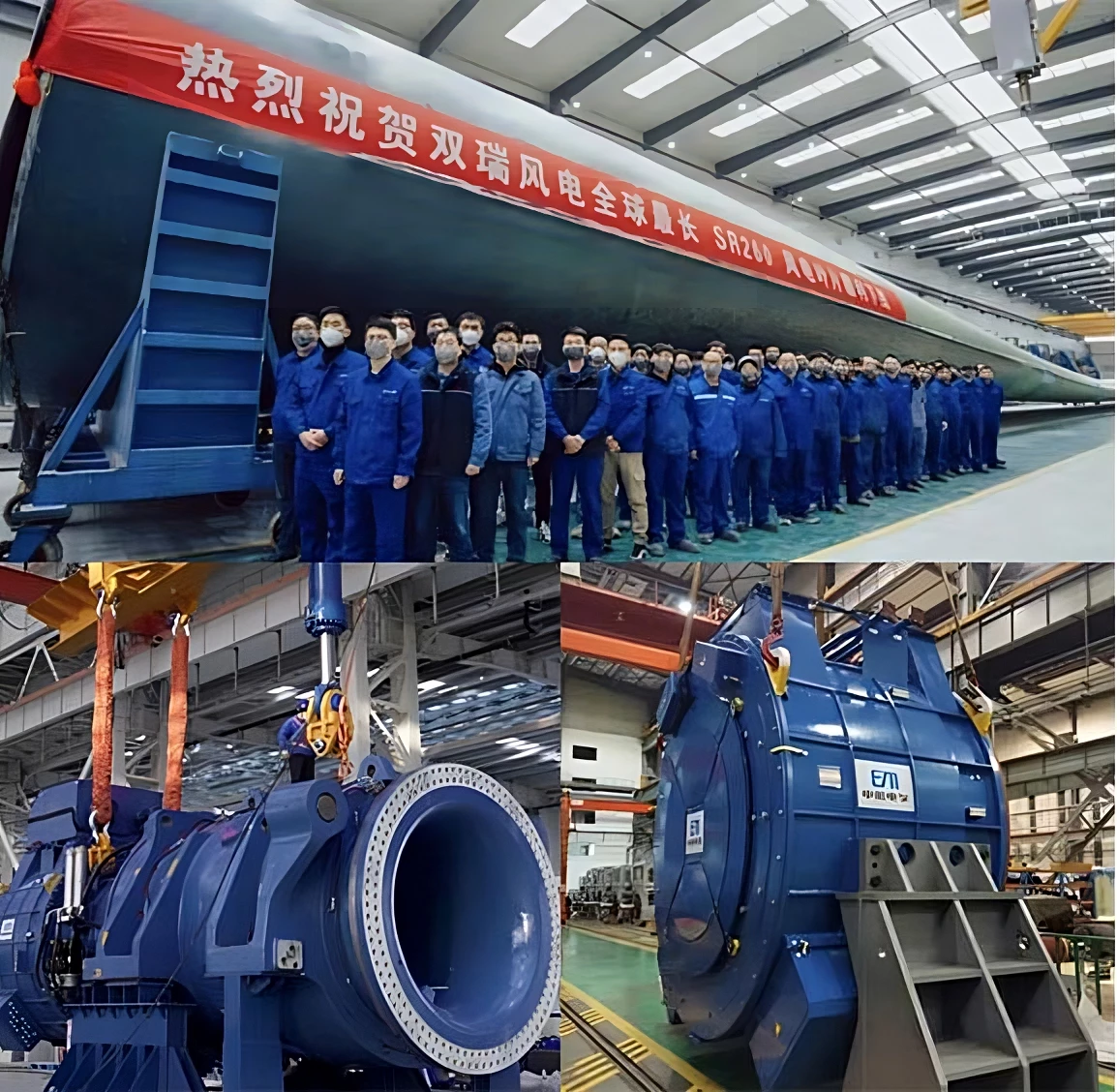

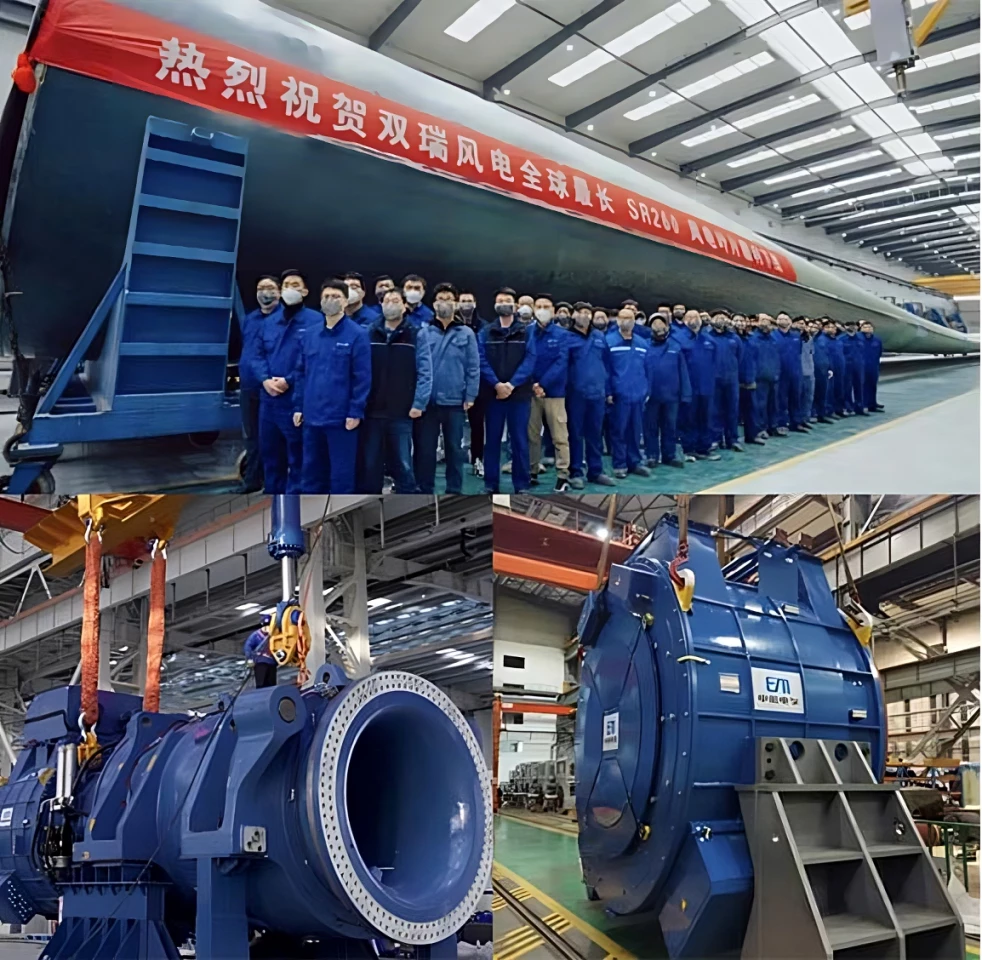

Either way, it'll be interesting to learn how they perform in the real world – and CSSC Haizhuang appears to be well into production of the first unit. Building the vast majority of the components in its own factories to avoid supply chain issues, it seems the company has already created at least one of the mammoth SuperBlade+ wings for this thing, as well as the giant generator, the gearbox, the frame, and one of the biggest bearings we've ever seen. Indeed, the main nacelle appears to be more or less assembled, and the hub to which the blades will be attached looks pretty darn close, too.

Source: CSSC Haizhuang