Engineers go to great lengths to maximize the exposure of wind turbines, placing blades atop tall towers on the crests of hills or miles off shore over the wild, unprotected ocean. A new study has thrown up an interesting curve ball that could open up new avenues for the generation of renewable energy, demonstrating how turbines nestled behind hills could actually produce higher amounts of energy than those out in the open.

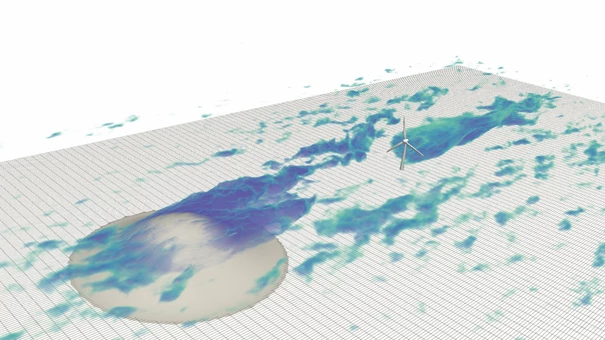

The research was carried out at the University of Twente in the Netherlands, and sought to explore how, in some circumstances, wind turbines could actually benefit from being placed behind hills. The scientists did this through an aerodynamic modeling technique called large eddy simulation, which allowed them to simulate the effects of a three-dimensional hill on the performance of downwind turbines.

The simulation was based on a 90-meter-tall (295-ft) turbine with 63-meter (207-ft) blades, being placed 756 meter (2,500 ft) behind a 90-meter-tall (300-ft) tall hill. Counterintuitively, the team found that under some conditions this particular arrangement actually increased the power production of the turbine by around 24 percent.

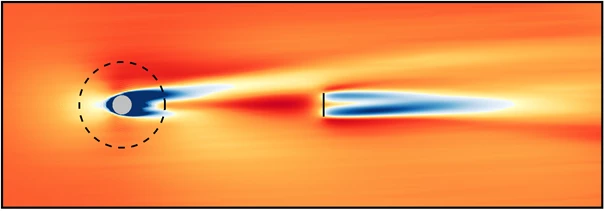

“The wind speed immediately behind the hill is slower, which creates an area of low pressure," explains study author Dr Richard Stevens. "This low-pressure area sucks in air from above, where the wind is much stronger than it is close to the ground. This means that a wind turbine does not need to be higher to take advantage of the strong winds at higher altitudes.”

This effect combines with another one relating to changes in wind direction as it blows over the hill, which drives up the intensity of the forces as they sweep across the turbine.

“In addition, the wind above the hill blows in a different direction to the wind close to the ground," says Stevens. "This causes the slow-moving air to bend away from the wind turbine (see above), leaving the turbine behind the hill to benefit from the strong current."

While the study demonstrates that some turbines placed behind hills in certain environments could produce greater amounts of power, there are other factors to consider. The simulations show that this increase in wind leads to higher amounts of turbulence, which would cause greater wear and tear on the turbines. The scientists are continuing to research whether the benefits outweigh the type of damage the turbines might incur, and whether this uptick in performance can be replicated across broader, real-world settings.

“For this particular situation, with only one hill, energy production is higher but real-life terrain is much more complex,” says Stevens.

The research was published in the journal Renewable Energy.

Source: University of Twente