A decades-old scientific controversy and a small bench-top apparatus at the University of British Columbia (UBC) could be the key to more efficient fusion reactors by increasing the chances of a nuclear reaction occurring.

In March 1989, electrochemists Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons stunned the world with the announcement that they had essentially achieved nuclear fusion in a jam jar. They claimed that by means of a simple glass container filled with heavy water into which were inserted a palladium cathode and a platinum anode, they were able, through electrolysis, to cause deuterium atoms to fuse within the palladium lattice.

It was an astounding bit of news to say the least. If verified, it would have not only overturned established nuclear physics, but revolutionized the world by making fusion power available to the world in a package about the size of a car battery.

It was too good to be true and for good reason – because it was.

It turned out that the work of the two men was extremely sloppy, impossible to reproduce, and based on all sorts of assumptions and errors. By the end of the year, the cold fusion bubble had burst, the technology was discredited, and the concept relegated to bad spy fiction and conspiracy theories.

Now, palladium in a jar connected to nuclear fusion is being revived but in a different guise. One of the problems with nuclear fusion is getting the reaction started, which requires a heavy concentration of the hydrogen isotope deuterium. It's a process that in itself can be energy intensive, so the interdisciplinary team at UBC turned to an electrochemical process involving palladium to boost things.

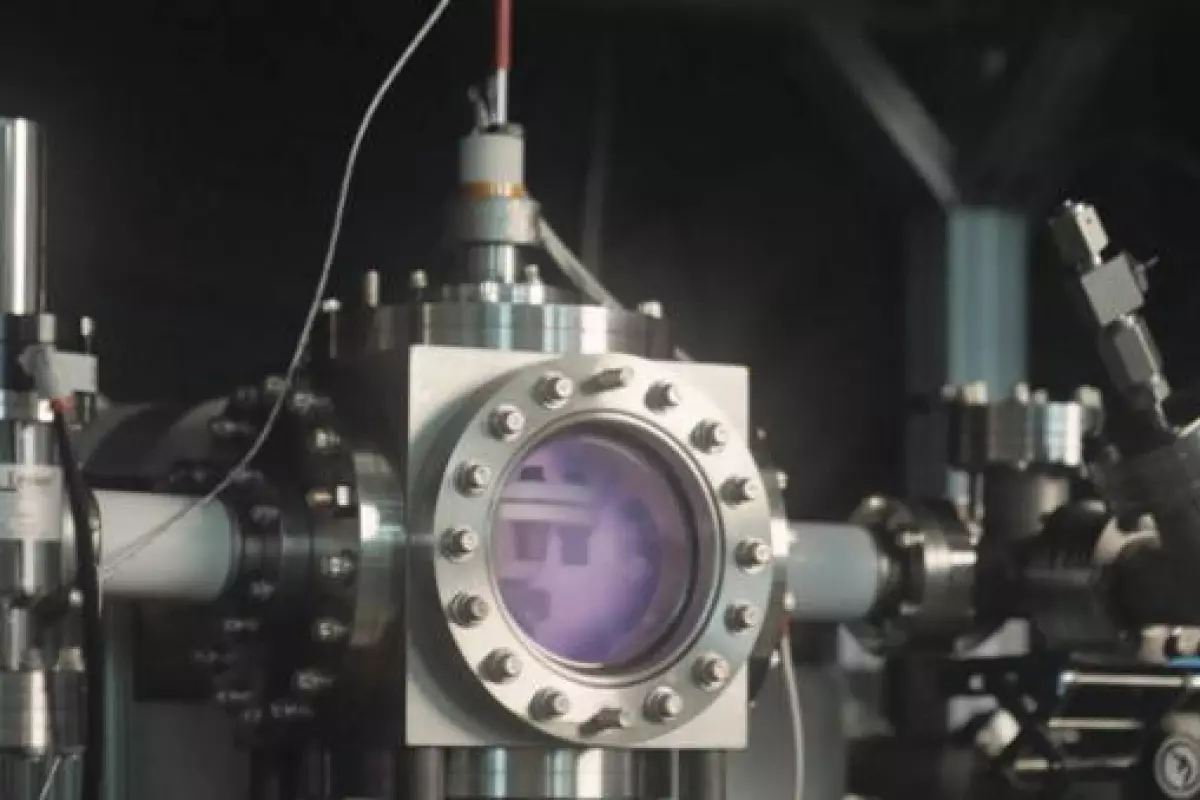

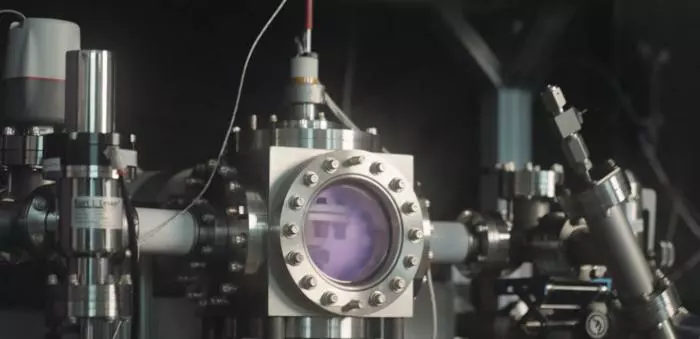

What they did was construct a target made out of palladium, and on one side of this they exposed it to an electrochemical reactor called the Thunderbird reactor. This generated a plasma field that loaded one side of the target with deuterium. Meanwhile, the other side of the target was subjected to another electrochemical cell that added more deuterium.

The clever bit is that by going the electrochemical route the team reported that they were able to use a single volt of electricity to load as much deuterium as normally took 800 atmospheres of pressure using conventional methods.

Since fusion reactions rely on fusing deuterium atoms, this overloading greatly increased the odds of this happening by an average of 15%. Though it didn't produce a net energy gain, the team believes that this opens new paths towards practical fusion power.

In addition, in case anyone is wondering, the team made clear that the experiment is reproducible and, unlike the 1989 experiments, they confirmed the results by neutron output rather than a mere rise in heat as the failed '80s attempt did.

"We hope this work helps bring fusion science out of the giant national labs and onto the lab bench," said Professor Curtis P. Berlinguette, corresponding author of the paper. "Our approach brings together nuclear fusion, materials science, and electrochemistry to create a platform where both fuel-loading methods and target materials can be systematically tuned. We see this as a starting point – one that invites the community to iterate, refine, and build upon in the spirit of open and rigorous inquiry."

The research was published in Nature.

Source: UBC