It's hard to ascertain how many birds fly into the spinning blades of wind turbines and die as a result – and indeed, the topic is so politically charged that I'd recommend a radiation suit before even googling it. The American Bird Conservancy has waded through some of the available evidence and come to the conclusion that at least one million bird deaths a year in the US alone is likely to be an underestimate.

Now, that's substantially less than the estimated 25.5 million birds a year that kill themselves by flying into overhead power lines, or the estimated 980 million per year that die crashing into buildings, or the 1.4 to 3.7 billion per year killed by domestic cats. But it's still an unacceptable number, and a problem that needs to be addressed – because a fully green energy network will need more and more turbines over the coming decades.

Researchers at SINTEF and the Norwegian Centre for Environment-friendly Energy Research believe they have an idea that could help in a lot of cases.

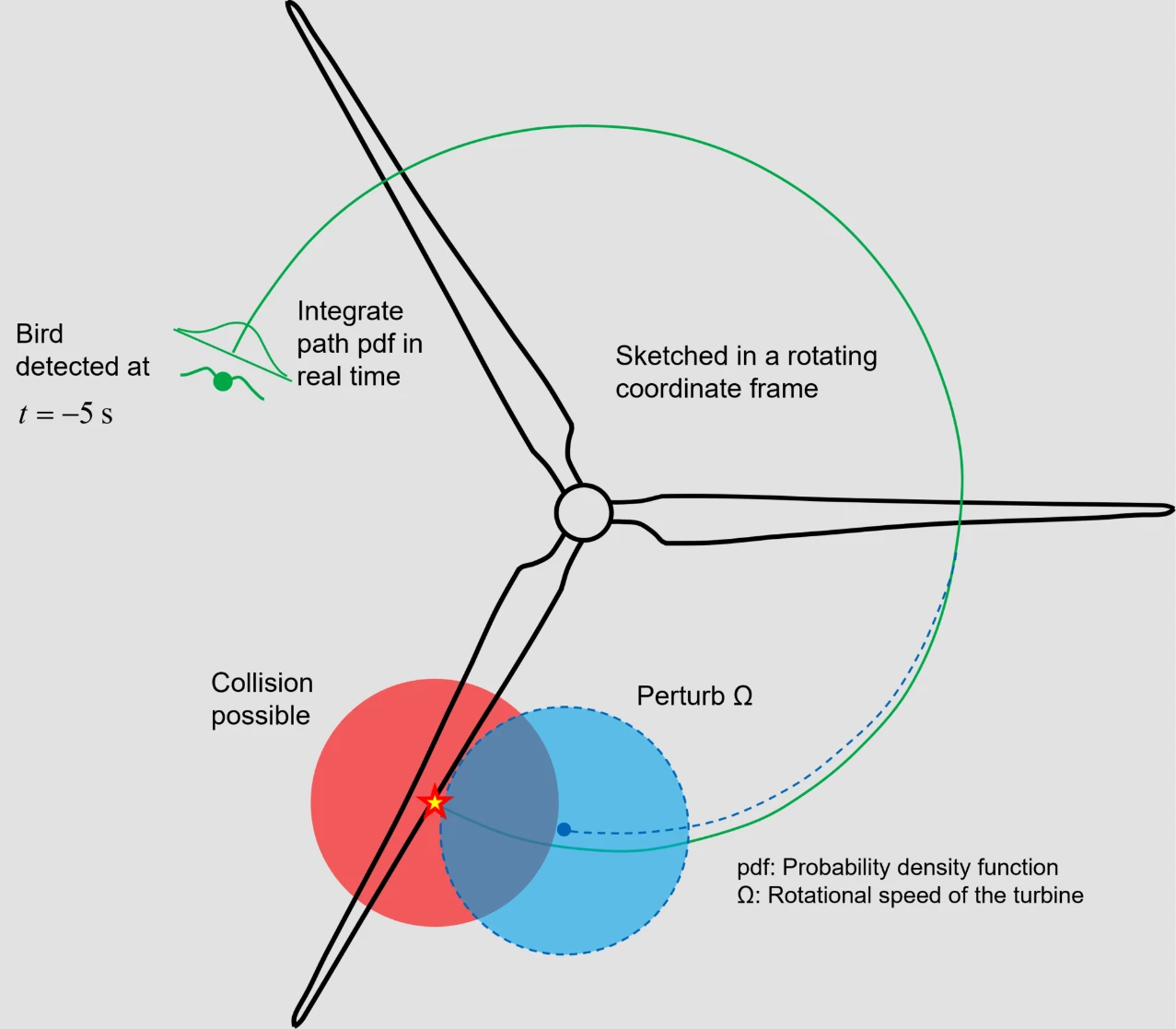

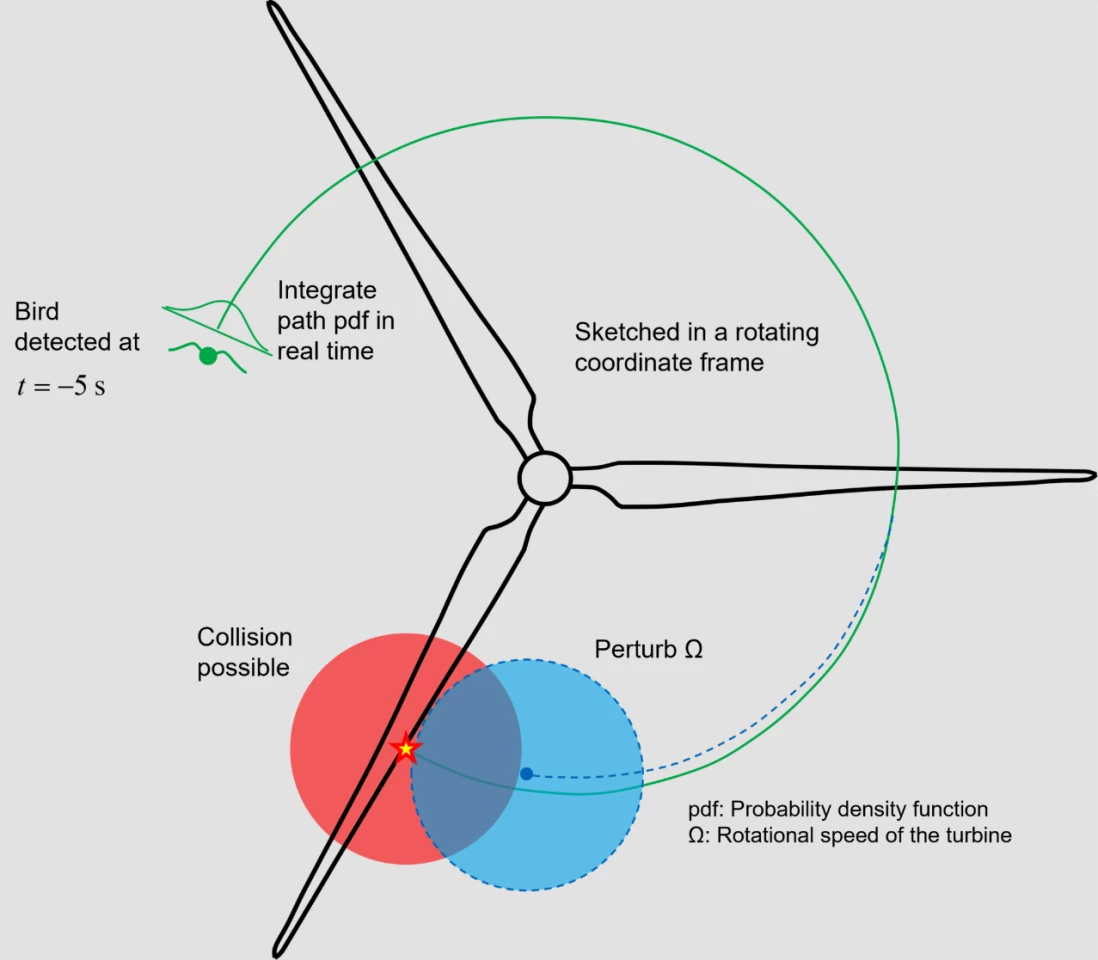

The idea is fairly simple: each turbine will have cameras fitted, capable of spotting birds flying directly into the path of the rotors. Software will automatically calculate their predicted trajectory, and if it looks like they're in danger of being hit, the system will send control signals to slow the blades down, by adjusting the generator moment and blade twist.

In simulations, the system – known as SKARV – is able to avoid the vast majority of collisions with single birds moving in a predictable path, coming toward the turbine head-on, spotted with at least five seconds until impact. This, of course, doesn't describe all situations. It won't stop them smacking into the central nacelle or the tower, and it won't help if they come flying in from the sides, or if they're circling around the turbine.

"It’s difficult to predict a bird’s flight trajectory, and the new system will not resolve this problem entirely,” says researcher Paula B. Garcia Rosa. “For example, if a young, inexperienced bird approaches a turbine displaying irregular flight behavior, it will not be possible to predict exactly where it will be a few seconds later. Prediction is also more difficult if several birds approach at the same time.”

The system can be set to shut turbines down altogether if a large number of birds are approaching – although the team notes it can take up to 20 seconds for a large turbine to stop completely from a normal rotation speed.

“On the basis of our simulations, we believe that the SKARV project can help to reduce the number of fatal collisions by up to 80%,” says Garcia Rosa. “The next step is to further develop existing strategies for controlling blade rotation speeds and to integrate these with methods for identifying bird flight trajectories. Then we will be looking to implement a practical demonstration. We believe that the SKARV technology could be commercially available within five years, and perhaps even earlier if we see sufficient interest from the industry."

This is one of those funny issues that turns coal magnates into environmentalists. If flocks of birds are going to regularly interrupt clean energy generation, the SKARV system may well also turn clean energy magnates into hard-hearted mercenaries. Some researchers even contend that birds are learning to avoid turbines of their own accord. But if more than a million birds a year – just in the USA – haven't got the memo yet, it's still a problem worth solving. We look forward to hearing how trials progress.

Check out a short video below.

Source: SINTEF