A new study by Stanford University suggests that an 80-mile-wide (130-km) stream of ice in the heart of Antarctica's "doomsday glacier" may expand over the next 20 years, which would increase its ice loss and contribute to sea level rises.

Located in West Antarctica, Thwaites Glacier has in some parts been clocked moving at speeds of over 2 km (1.2 miles) per year. That may not seem quick by everyday standards, but for a glacier that's really shifting. Thwaites Glacier is regarded as part of the weak underbelly of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet that may be vulnerable to collapse or have its outflow speed up enough to significantly contribute to global sea level rises.

Previous computer models of how the glacier moves have concentrated on its speed and thickness and how these might change over the centuries, but the new study led by Jenny Suckale, assistant professor of geophysics at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability, suggests that the width of the main ice stream, or trunk, could make the glacier more or less stable, with a wider stream making it less stable and a narrower stream making it more stable.

Essentially, it's like watching the eroding effect of a widening river on its banks. In this case, a widening of only 2% could lead to significant ice loss, releasing billions of tonnes of water into the Amundsen Sea while opening up a path for more ice to follow.

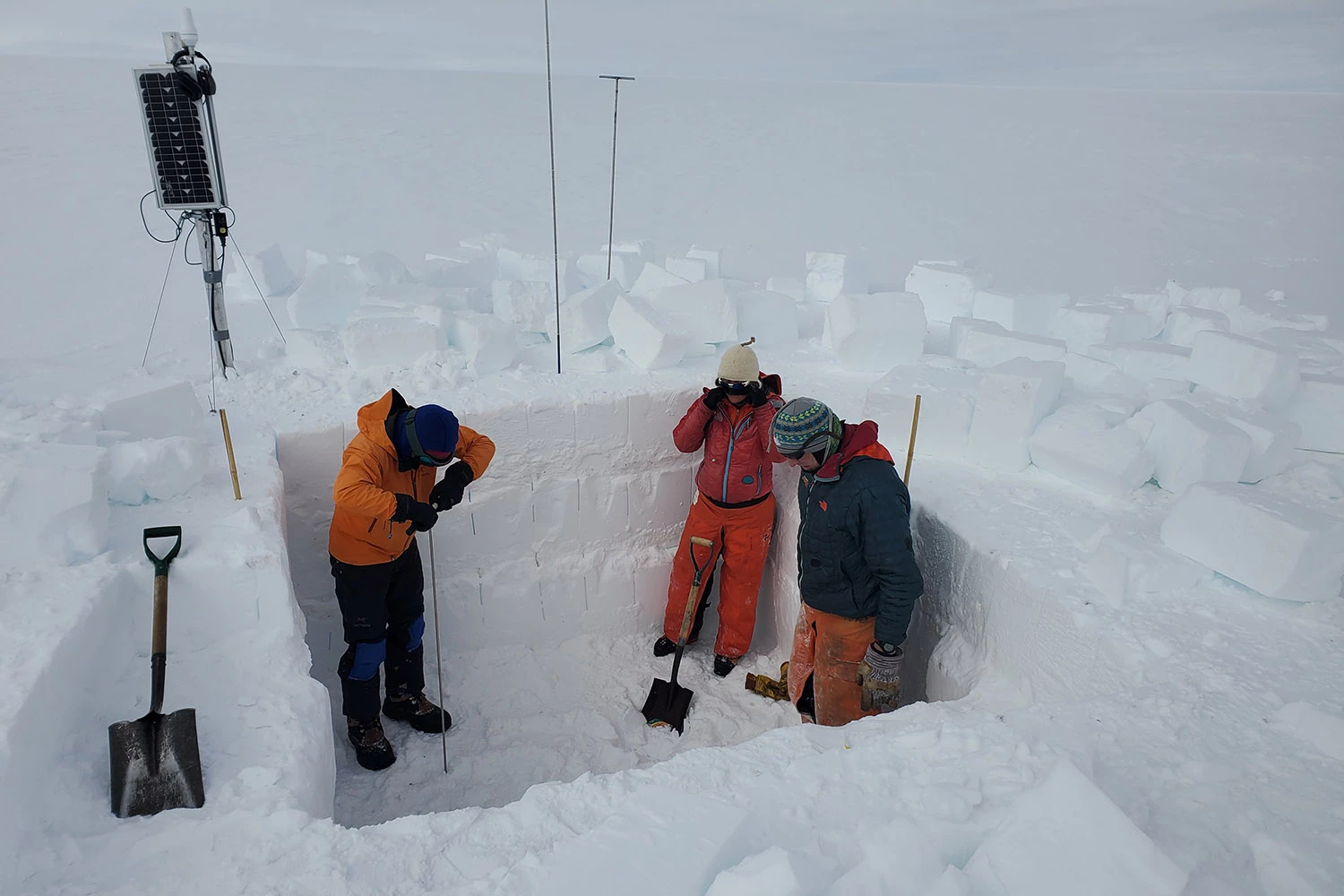

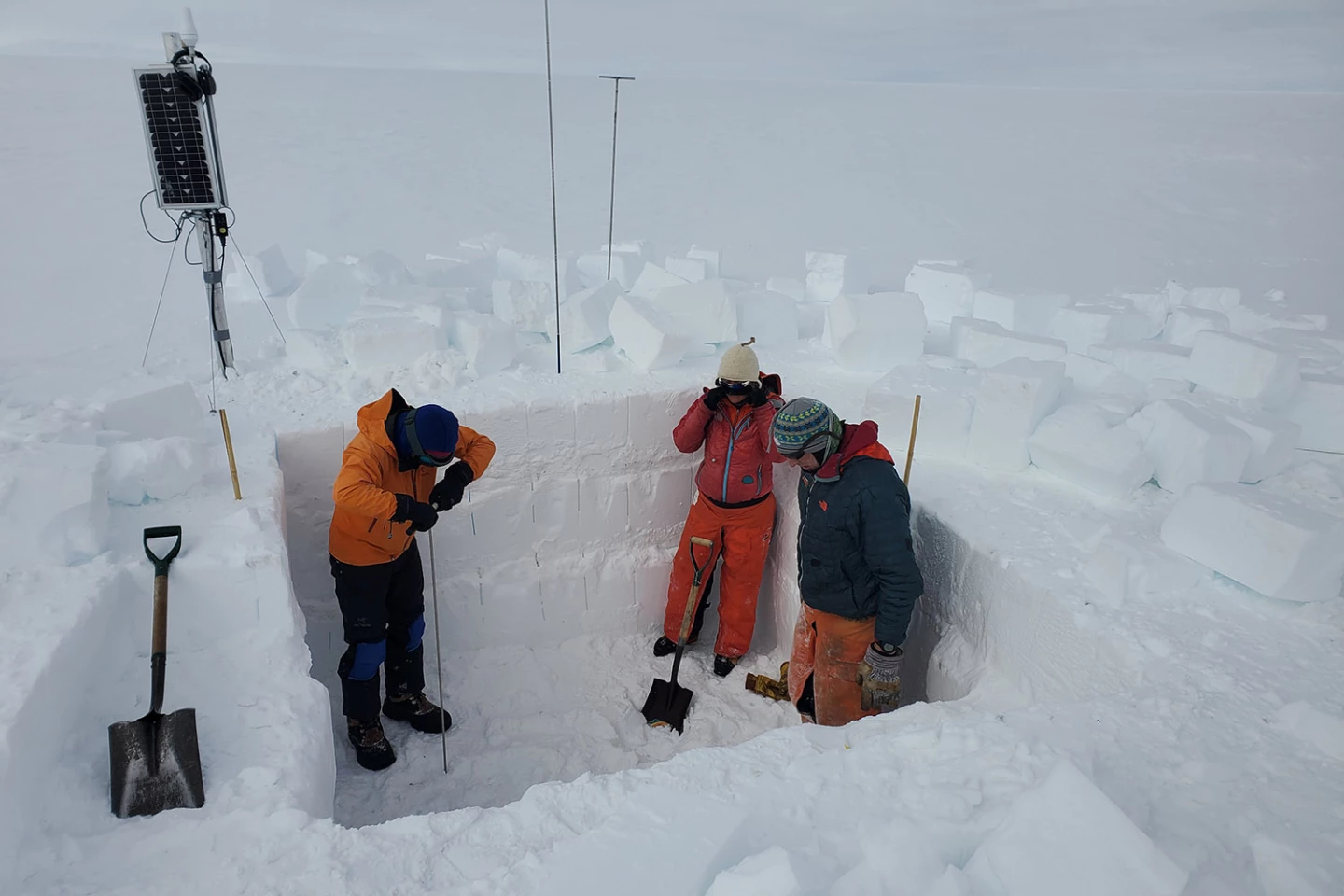

The team stresses that, while the worst-case scenario makes it important to keep a close eye on Thwaites Glacier, it isn't the only possible outcome. It's also possible that the ice stream could, over time, narrow or remain the same width, resulting in greater stability. The key is to gather more data to build more reliable models and to determine the proper response to future events, ranging from flood management to population relocation.

"We are very intentionally focusing on the next two decades to enable testability and continued model development,” said Suckale. "It’s kind of like weather predictions. You monitor the storms as they come in, and then you update your predictions and pass that information on. I think we need to monitor Thwaites and make sure we have ways to get that information into planners’ hands. We don’t need to hit the panic button, but we also can’t ignore this."

The research was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth.

Source: Stanford University