Methylmercury is an extremely toxic compound, and unfortunately it's often present in the fish that we eat. Scientists are now developing a method of removing it from the environment, utilizing engineered fish and flies that take up the compound and neutralize it.

Known for being one of the most dangerous pollutants in existence, methylmercury is released into the environment via industrial activities such as the burning of coal.

Unfortunately it's highly bioavailable, meaning that it's easily taken up by the bodies of aquatic organisms that ingest it while eating. It passes through the linings of their digestive tracts and into their tissue, where it stays and accumulates throughout their lives.

Worse yet, as smaller organisms get eaten by larger ones, the contamination makes its way up the food chain, increasing exponentially as it goes. Eventually, it passes into humans who eat contaminated fish. As the mercury levels increase in those people, damage may occur to their nervous system, kidneys, or even their unborn children.

In an effort to address this problem, Dr. Kate Tepper and Assoc. Prof. Maciej Maselko from Australia's Macquarie University looked to something that's already at home in the environment anyway – fish and flies.

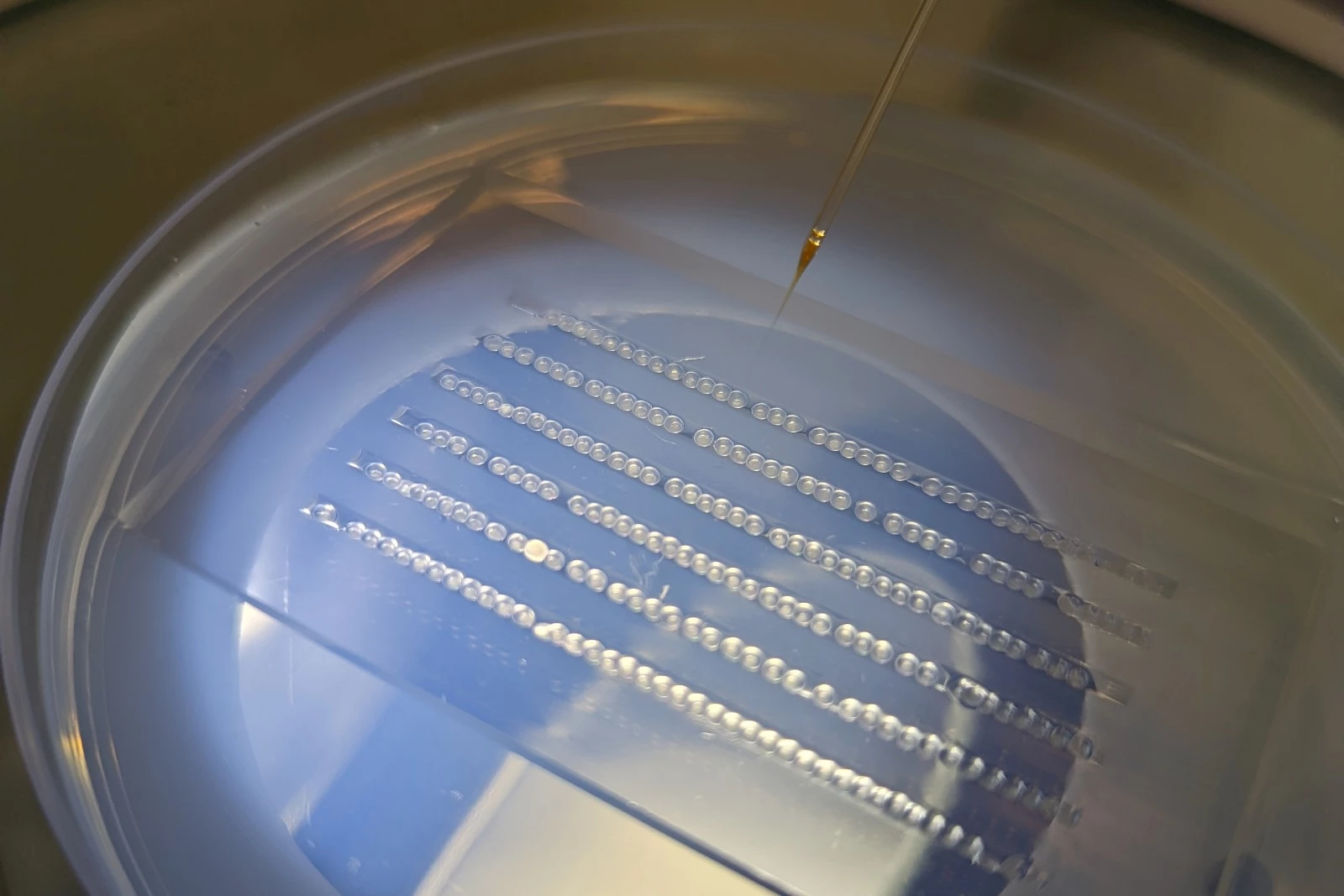

The scientists genetically modified zebrafish (aka zebra danios) and fruit flies by inserting variants of genes from E. coli bacteria into the animals' DNA. Doing so caused the creatures to produce two enzymes that convert ingested methylmercury into a far less harmful substance known as elemental mercury.

In lab tests, it was found that most of the elemental mercury evaporated in gas form from the animals' bodies. Tepper tells us that in the case of the zebrafish, the gas was likely passed through their gills, although it could also have been released through their skin, urine or feces. Whichever the case, it wouldn't pose a danger in the open environment.

"Mercury gas can be a problem in certain occupational settings, where it can reach a higher level, but in environmental settings it is too dilute in our atmosphere to act as a toxin," she explains.

What's more, elemental mercury is much less bioavailable than methylmercury, meaning that it has much less of a tendency to accumulate in the body. As a result, the modified fish and flies accumulated less than half as much mercury as their counterparts in the control groups.

The animals have also been modified so that they can't reproduce in the wild, but more research still needs to be conducted before they can be released into the environment. That said, the flies or other insects could alternatively find use in industrial settings.

"An application for this technology we are excited about is modifying insects that can process organic wastes commonly contaminated by mercury, and in the enclosed industrial facilities the mercury gas can be trapped and removed from the biosphere," Tepper tells us. "These insects can process treated sewage for example, which is estimated to be responsible for releasing a quarter of the world’s mercury into the environment."

A paper on the research – which also involved scientists from CSIRO and the ARC Centre of Excellence in Synthetic Biology – was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

Source: Macquarie University