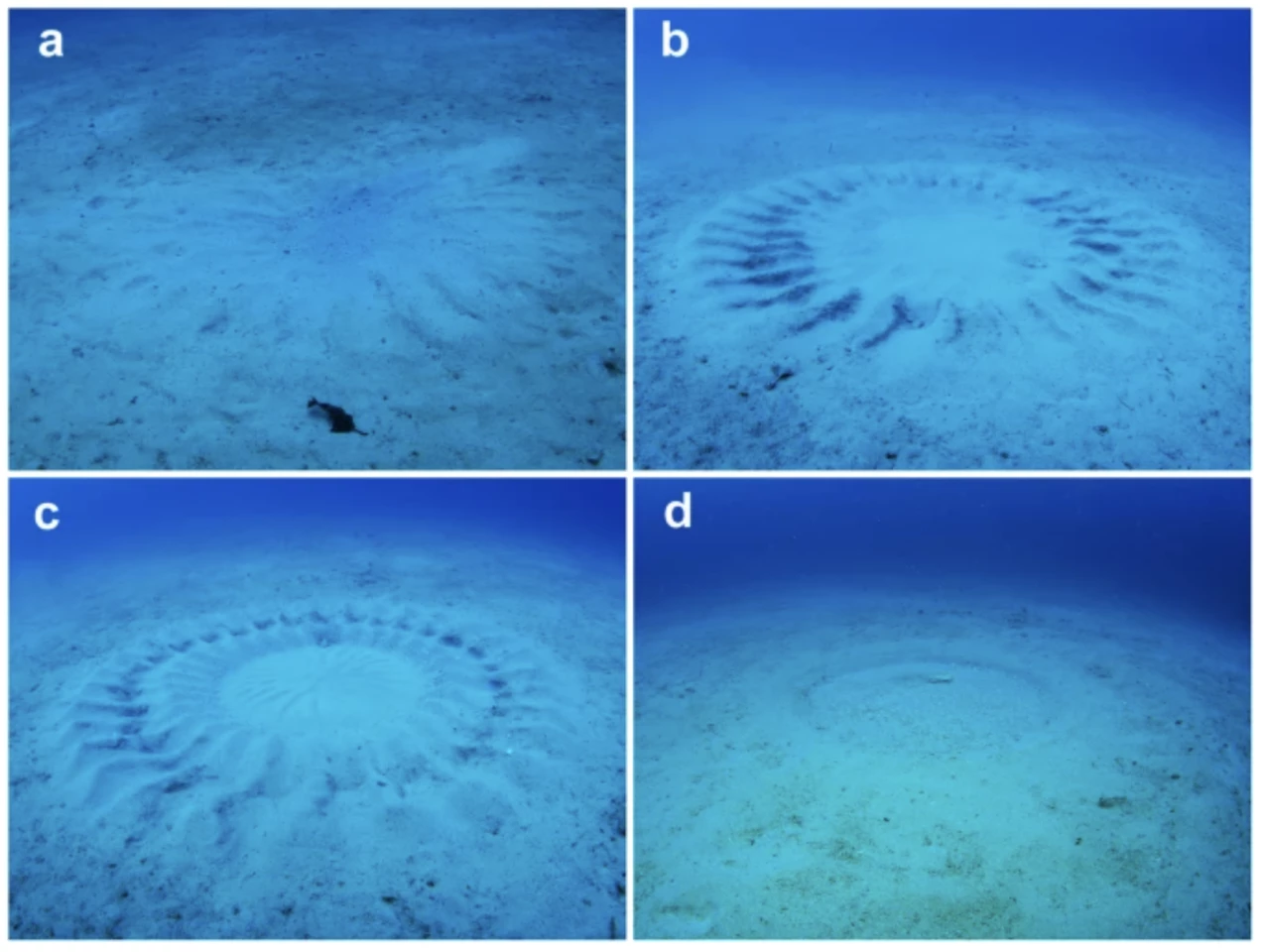

In 1995, divers first noticed a group of bizarre sandy "crop circles" on the seabed around Amami Oshima Island, southwest Japan. But it took decades for scientists to identify the marine artists behind them – and why they were building such geometrically precise structures every year.

These circles can reach two metres (6.6 feet) in diameter and are etched into otherwise featureless sandy seabed. But they're not just circular mounds of sand – they feature ridges and grooves that fan out from a central zone like the spokes of a wheel, appearing deliberate and well built. And for years, researchers had them down as simply one of those ocean mysteries.

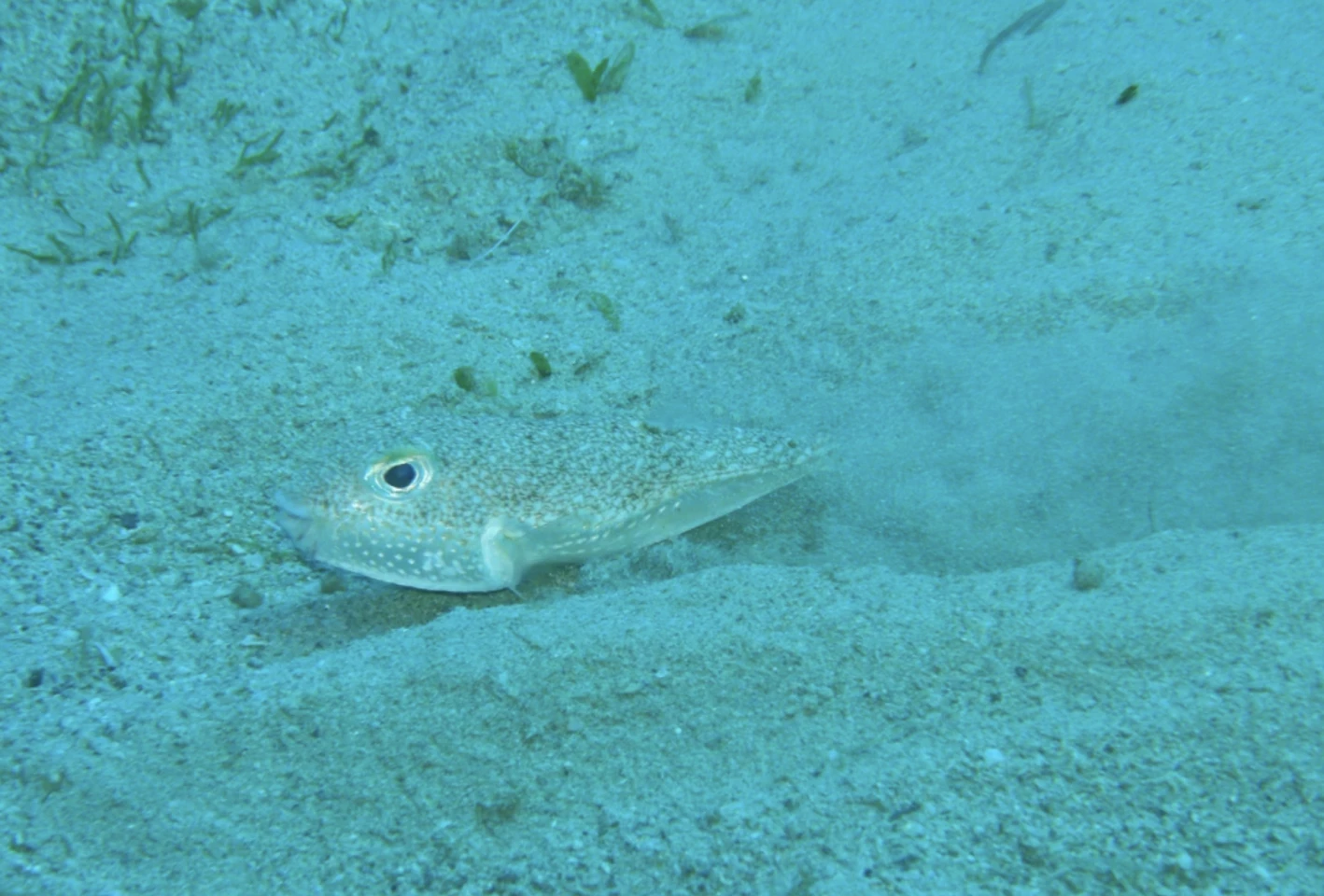

However, when scientists did find out what was causing them, the answer was almost as strange. These were the impressive work of a small male pufferfish, around 10-cm (3.4-in) long, belonging to the genus Torquigener, who painstakingly used their fins as tools to construct these underwater megastructures in an effort to attract a female – and to engineer a safe, calm environment for eggs to develop. It's such an impressive feat that Sir David Attenborough has even described this fish as “probably nature’s greatest artist.”

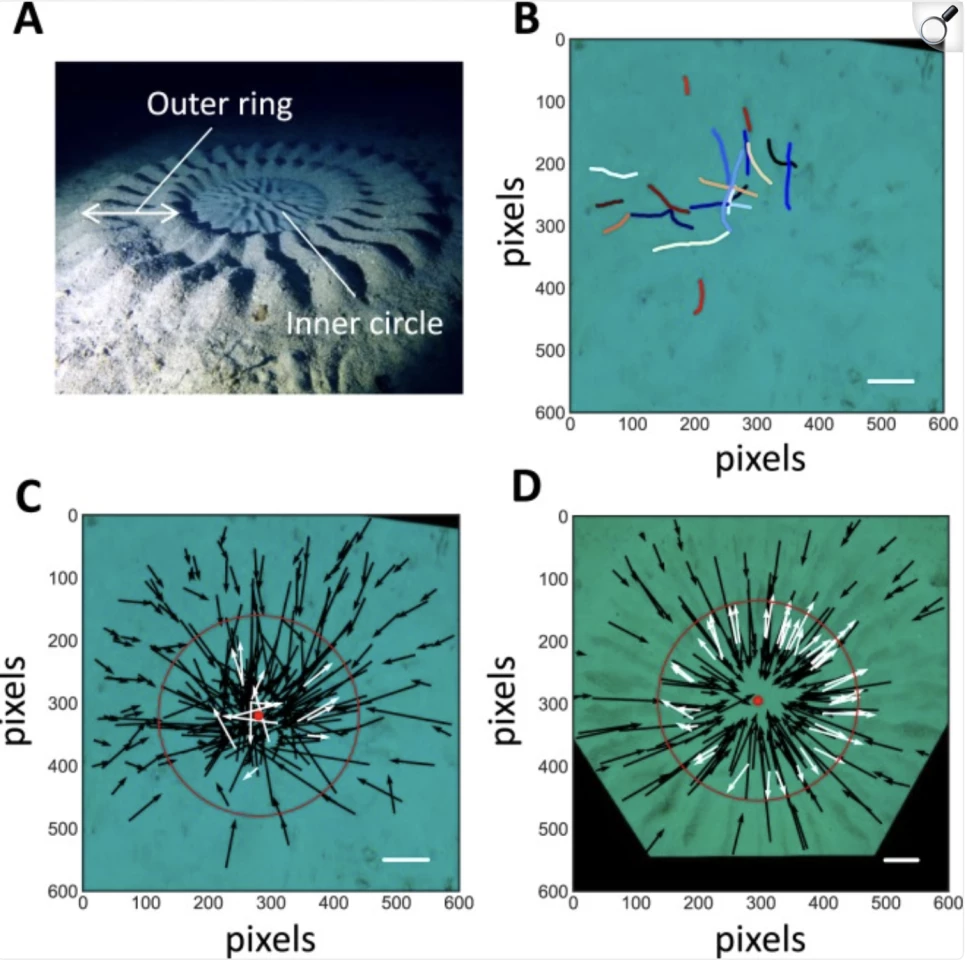

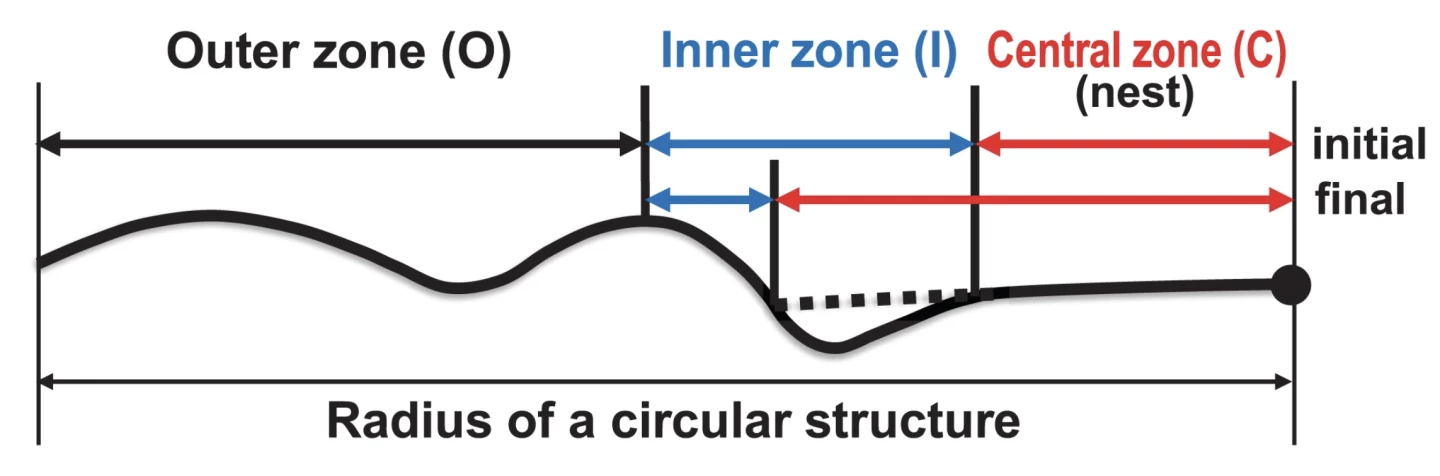

"The circle consists of radially arranged deep ditches in the outer ring region, and maze-like shallow ditches in the central region," researchers wrote in the breakthrough Nature: Scientific Reports paper. "During construction, the pufferfish repeatedly excavates ditches from the outside in. Generally, excavation starts at lower positions, and occurs in straight lines. The entry position, the length, and the direction of each ditch were recorded. A simulation program based on these data successfully reproduced the circle pattern, suggesting that the complex circle structure can be created by the repetition of simple actions by the pufferfish.

"The nest structure is much more geometrically ordered than any known nests built by other fish," they added.

While we don't know if every pufferfish is capable of such elaborate builds, scientists repeatedly observed it among the white-spotted pufferfish Torquigener albomaculosus species in Japan. To begin construction, the male pushes its belly on the sandy seabed to make a central spot in the future circle. It then repeatedly excavates sand with its fins and body, leaving hundreds – and sometimes thousands – of marks. During this process, radial ditches in the outer ring that forms the distinct circle shape begins to emerge. Once this takes shape, the fish heads back into the middle of the "nest" and further reshapes the surface to form a maze-like structure. The circles are visible from above the water, even though they're built on the seabed at depths of between 10 m (33 ft) and 30 m (66 ft).

Overall, the structure features large circular “outer ring” with many radially arranged peaks and valleys, and a central zone that’s relatively flattened but etched with a finer, maze-like pattern. The circle's center also becomes enriched in fine sand grains, and the ridges may be decorated with shell/coral fragments.

Why go to such effort for just a temporary structure at the mercy of the currents? Well, they play a key role in reproduction and female choice. The scientists found that once the male has completed his work, females inspect its nest and others, before choosing the most appealing structure for spawning near the center of the circle. One preference the females seem to have is fine sand – this is also the first to degrade in the circle, meaning the male won't reuse his masterpiece but build from scratch when another mating event requires it.

All up, construction takes about seven to nine days, during which the male maintains the geometry by swimming along the sand and fanning its fins, creating straight-line segments. A later Scientific Reports study revealed more about the important details of the circle – such as where the female enters, depth of each ditch and the rigid directional order in which the male works on the design.

A study in Fishes documented in more detail how the circles get built, starting with numerous irregular depressions, forming a primitive circle with radially aligned ditches and a central depression by around day two. Over the next week, the fish increases the amount of ridges and valleys, until it's complete and the circle's outer peaks are decorated. Researchers have also analyzed fish movements and found that the elegance of the final structure isn't due to complex cognition, but from the repetition of simple actions – a phenomenon known as "emergent complexity."

And this design also plays a key function in sorting the circle's sediment, making it extremely functional and built for purpose. Fascinatingly, the circular nests aren't built to "trap" eggs laid by the female, but the design is specifically focused on encouraging retainment of a certain type of sand grain. The circular ridges don’t act like a physical wall to hold the eggs in place, but they reshape how water moves across the seabed, and what grains of sand accumulate inside it.

As currents pass over the structure, the peaks and valleys redirect flow sideways and around the circle rather than straight through its center. This breaks up the current and creates a calmer zone in the middle, where fine sand grains gather. The effect provides enough movement to keep the central region oxygenated, without the stronger current that would otherwise disturb it. Experiments and field observations showed that fine sand particles get carried inward and settle in this central zone, providing a soft, safe patch for females to use as a spawning site.

When a female arrives, she inspects the circle, swimming along its ridges and over the center before deciding whether to spawn there. If she likes what she sees, eggs are laid in the fine sand in the middle. Once spawning is complete, with the eggs safely deposited in the fine-sand calm micro-environment, the circle begins to degrade and ultimately vanishes faster than it took to build. While the male sticks around to keep watch over the developing eggs, the fish makes no attempt to maintain the circle – and when the next breeding cycle arrives, it'll once again build an entirely new nest somewhere else.

"After spawning, males remained in the circular structure for six days to care for the eggs," the scientists observed in that landmark study. "They did not perform digging or other maintenance behaviour of the radially aligned peaks or valleys during this period. As a result, the structure gradually collapsed and was smoothed to become almost flat by water currents. Furthermore, the fine sand particles were dispersed and replaced by coarser sand particles, which covered the nest site. After the eggs hatched, males left the nest site and soon reappeared in the observation area for the next reproductive cycle. However, they never returned to an old nest site but instead began to construct a new circular structure at a separate site."

While much of what we know of these circles comes from the work of the T. albomaculosus, which had led scientists to believe this species might be unique in building their elaborate sand castles, a 2020 study upended that when researchers discovered that an unidentified pufferfish was also constructing these circles at greater depths off the coast of northwest Australia. In the study, a hybrid autonomous underwater vehicle (HAUV) recorded a high-resolution video and bathymetric data of 21 circular formations that looked eerily similar to those observed near Japan. The first to be seen in Australian waters, the circles were constructed at a depth of at least 129 m (423 ft) – and more than 5,500 km (3,418 miles) from those observed near Japan.

"Such a discovery not only generates intrigue and wonder among scientists and the general public but also provides an insight into the reproductive behaviour and evolution of pufferfish globally," the researchers noted.

Specimens are still needed to confirm if the Australian builders are a population of T. albomaculosus or one of the pufferfish living in waters at that depth – T. parcuspinus, T. tuberculiferus and T. pallimaculatus, specifically – so we don't know if these intricate displays of love are widespread in the genus or just the work of one talented species.

In 2022, scientists built a 3D model of the famous original "mystery circle," detailing the incredible work of the male pufferfish that use physics and nature to reproduce in the challenging underwater environment.

You can see the pufferfish in action, creating his elaborate nesting site, from a BBC Earth episode, narrated by Attenborough.

Source: Scientific Reports 2013 and 2018, Fishes, Journal of Fish Biology,