Scientists in the UK have developed a new method for removing toxic “forever chemicals” from wastewater. Specially treated, 3D-printed ceramic lattices can remove up to 75% of the chemicals from polluted water in three hours – and the structures get better at their job as they’re reused.

One of the most pressing environmental and health concerns currently is a group of chemicals known as perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Wide use for the better part of a century has spread these chemicals across the planet, and they don’t break down, leading to the nickname of “forever chemicals.” Inevitably they end up in our bodies, where they’ve been linked to a range of health problems, from diabetes to various cancers.

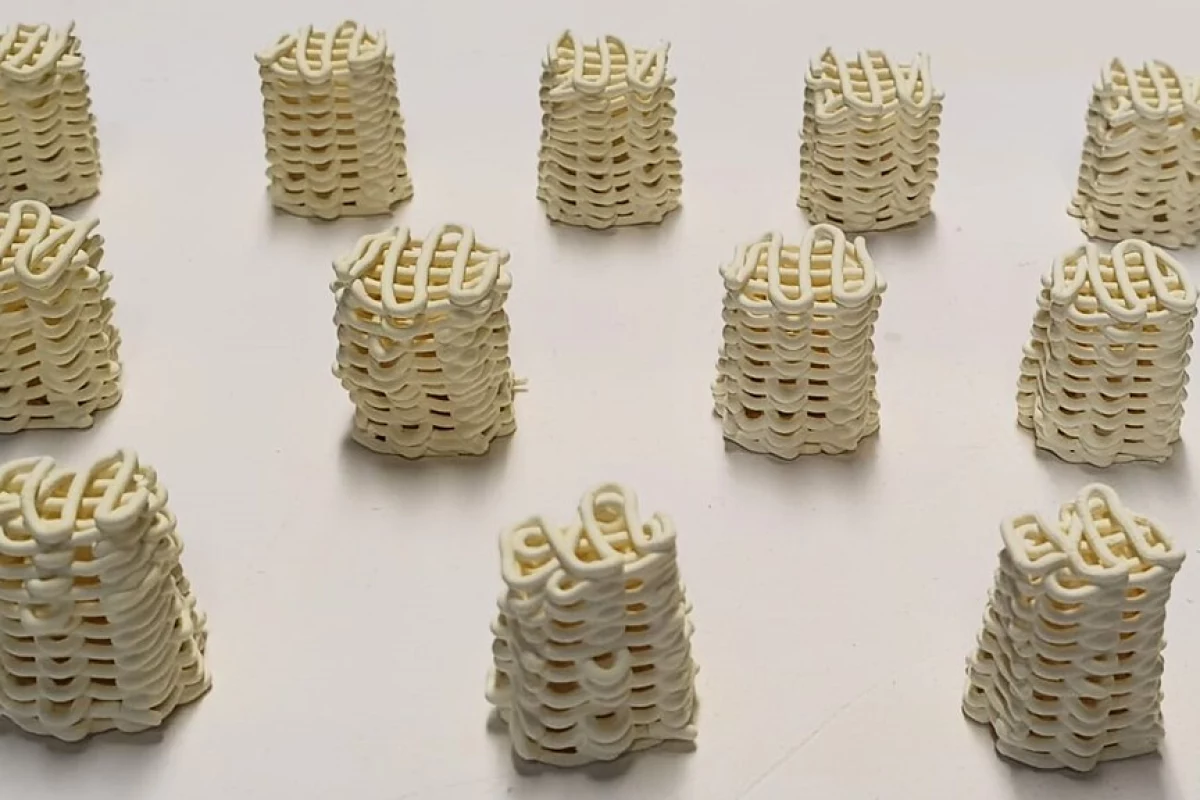

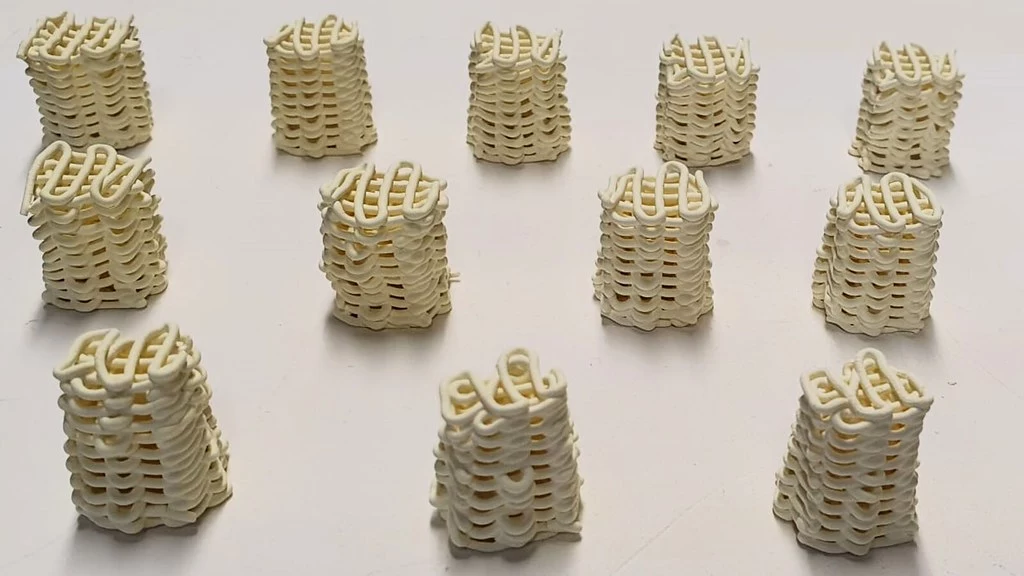

Now, scientists at the University of Bath have demonstrated a new potential way to remove PFAS from water. The idea is to use 3D printed “monoliths” made of ceramic materials infused with indium oxide, which bonds with PFAS molecules. These monoliths can be soaked in polluted water for a few hours, and when they’re removed the PFAS go with them. They can then be treated to remove the chemicals and allow the monoliths to be used again.

While many 3D-printed structures require fine detail, these are made of much thicker “noodles” of material, like toothpaste squeezed out of a tube into a structure that looks like a stack of waffles. The goal of that is not only simple manufacturing, but to maximize surface area to allow them to capture as much PFAS as possible.

In tests, these monoliths were initially able to remove 53% of a common PFAS called perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) from water in three hours. Pyrolosis treatment of the monoliths at 500 °C (932 °F) regenerated them, allowing them to be used again – and intriguingly, this actually boosted their ability to clean water. By the third cycle, the monoliths were removing 75% of the PFOA in three hours.

While there’s still more work to be done, the team says that arrays of these reusable ceramic monoliths could be a valuable step to add to existing wastewater treatment plants. Unlike other techniques that require catalysis, this process itself doesn’t require energy – that said, regenerating them via pyrolosis could be a sticking point.

“Using 3D printing to create the monoliths is relatively simple, and it also means the process should be scalable,” said Dr. Liana Zoumpouli, an author of the study. “3D printing allows us to create objects with a high surface area, which is key to the process. Once the monoliths are ready you simply drop them into the water and let them do their work. It’s very exciting and something we are keen to develop further and see in use.”

The research was published in The Chemical Engineering Journal.

Source: University of Bath