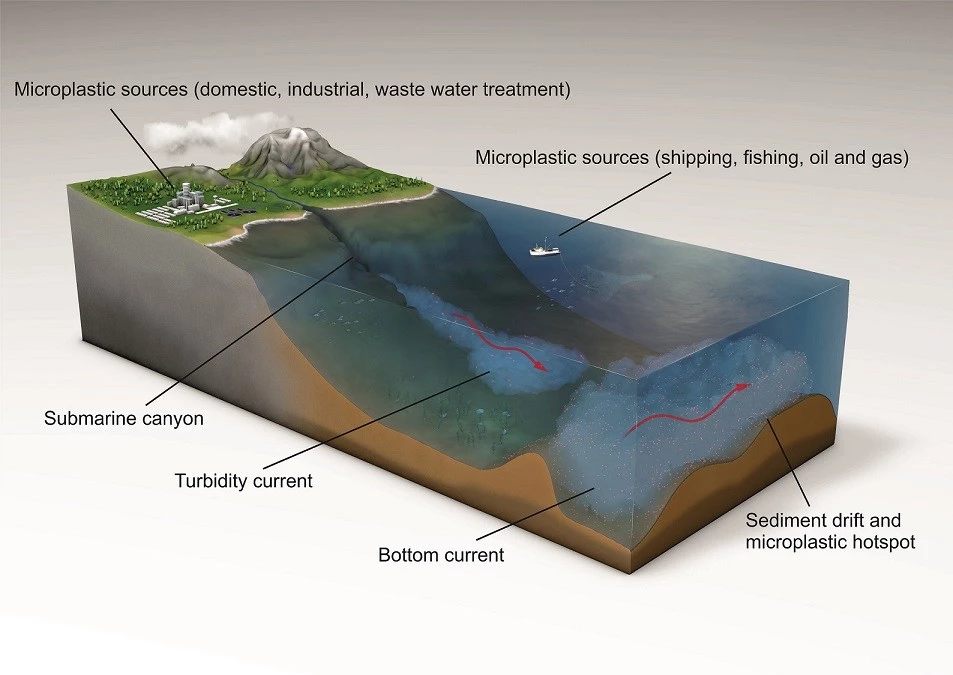

Millions of metric tons of plastic waste enter the ocean each year, but beyond that, we have little idea where much of it ultimately winds up. Researchers working to trace its path through the marine environment have discovered the highest concentration of microplastics ever recorded on the seafloor, an example of a hotspot of plastic pollution created by deep-sea currents that act like conveyor belts for our trash.

In late March, scientists at the University of Manchester published a study describing the results of tank experiments simulating sediment flows across the ocean floor, in which a type of underwater avalanche was found to drive tiny fibers of plastic from shore into the deep sea.

A new study from the same team builds on this knowledge, with the scientists collaborating with other researchers across Europe to explore how currents shape the flow of plastic waste in the deep sea. The team collected sediment samples from a part of the Mediterranean Sea, amounting to a thin layer covering one square meter (10.8 sq ft) of ocean floor. They then went to work analyzing the material and the surrounding currents to understand its makeup and how it came to be there.

This meant separating the tiny plastic particles from the sediment in the laboratory, and using infrared spectroscopy to determine the different types of plastic. In doing so, the team tallied up a grand total of 1.9 million pieces of plastic, the highest concentration ever recorded on the seafloor and the result of ocean currents that see them aggregate in certain locations.

"Almost everybody has heard of the infamous ocean ‘garbage patches’ of floating plastic, but we were shocked at the high concentrations of microplastics we found in the deep-seafloor," says lead author Dr Ian Kane from the University of Manchester. "We discovered that microplastics are not uniformly distributed across the study area; instead they are distributed by powerful seafloor currents which concentrate them in certain areas."

The team found that the majority of the microplastics embedded in this part of the seafloor were fibers derived from textiles and clothing, which slip through filters in waste water treatment plants and make their way out to sea. Given their abundance and the way they are transported through marine environments, the team likens these particles to any other sediment material you could expect to find on the ocean floor.

“It’s unfortunate, but plastic has become a new type of sediment particle, which is distributed across the seafloor together with sand, mud and nutrients," says Dr Florian Pohl from Durham University, who collaborated on the research. "Thus, sediment-transport processes such as seafloor currents will concentrate plastic particles in certain locations on the seafloor, as demonstrated by our research.”

These findings can help researchers better understanding how and why these hotspots form in particular locations, informing our broader knowledge of how plastic travels through the marine environment.

“Our study has shown how detailed studies of seafloor currents can help us to connect microplastic transport pathways in the deep-sea and find the ‘missing’ microplastics," says co-author Dr Mike Clare of the National Oceanography Centre. "The results highlight the need for policy interventions to limit the future flow of plastics into natural environments and minimize impacts on ocean ecosystems.”

The research was published in the journal Science.

Source: University of Manchester