It's a sad fact that threatened species of sharks are routinely caught on fishing lines intended for other types of fish. A new device could help change that, by harmlessly scaring sharks away from baited hooks via pulses of electricity.

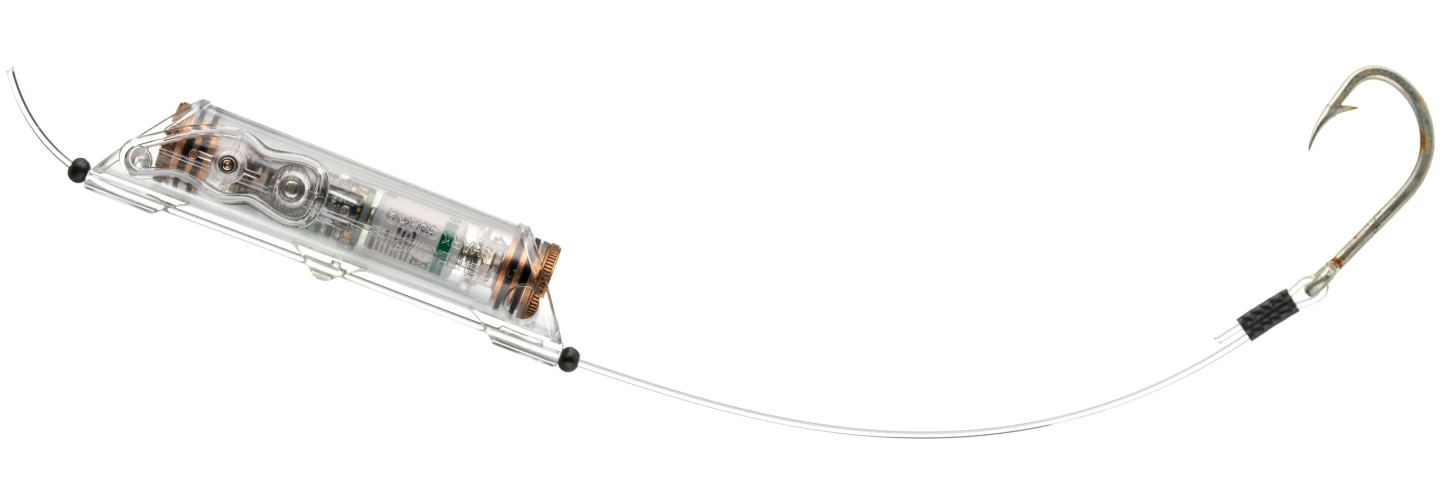

Known as SharkGuard, the gadget is manufactured by British company Fishtek Marine. It's designed for use on longline fishing rigs, which consist of a long main line with baited hooks attached at intervals via short branch lines.

Attached to each branch line directly above the hook, the SharkGuard emits a series of electrical pulses, creating a localized pulsating electrical field. The idea is that this field will overstimulate the sensory organs that sharks use to locate prey, causing the sharks to move off and leave the hooks alone. Devices used to keep sharks away from swimmers work on the same principal.

In sea trials which took place in July and August of 2021, scientists from the University of Exeter gathered catch data from two fishing boats in Southern France, both of which were using SharkGuards on some of their lines but not on others (the latter serving as controls). Between the two of them, the vessels made a total of 11 trips.

When the data was analyzed, it was determined that the SharkGuards reduced the bycatch of blue sharks by 91% – blue sharks are often unintentionally caught in the area. The bycatch of stingrays, which are closely related to sharks and are also often caught, was reduced by 71%.

It should be noted that the overall catch rate of the target fish, bluefin tuna, was down by 42% on both the SharkGuard-equipped and control lines. Because this may have been due to a natural fluctuation, further research will be required to better gauge the effect of the technology on target species.

"There is an urgent need to reduce bycatch, which not only kills millions of sharks and rays each year but also costs fishers time and money," said U Exeter's Dr. Phil Doherty. "Our study suggests SharkGuard is remarkably effective at keeping blue sharks and pelagic stingrays off fishing hooks."

Further, more extensive sea trials are now being planned. The research is described in a paper that was recently published in the journal Current Biology.

Sources: University of Exeter, Cell Press via EurekAlert