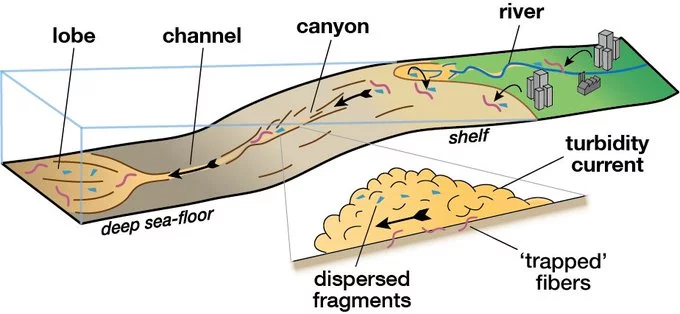

Millions of tons of plastic waste washes into the world's oceans each year, but a new study has revealed that it doesn’t all move through the water in the same way. Scientists investigating the movement of submarine sediment have found that so-called underwater avalanches are driving microplastics into the deep ocean, a finding that may help researchers better map the distribution of waste throughout the marine environment and enable the identification of future "microplastic hotspots" that could be targeted for study.

The research was carried out by scientists at the University of Manchester, Durham University and Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and looked at the impacts of shifting submarine sediment, which they describe as the largest flows on Earth.

To do this, the team set up experiments where quartz sand was mixed with fragments and fibers of microplastic inside a flume tank, which had been designed to simulate the sediment flows of the ocean floor. The scientists then analyzed how these flows shift sediment around and distributed the plastic materials across the seafloor.

The team’s analysis revealed that the avalanches distributed different types of microplastic in different ways. The microplastic fragments tended to build up in the lower parts of the flow, while microplastic fibers were distributed more evenly and took longer to settle. The scientists believe this is due to the larger surface area of the fibers, which also means they are more likely become caught up in grains of settling sand and ultimately become lodged in the deep seafloor.

“This is in contrast to what we have seen in rivers, where floods flush out microplastics; the high sediment load in these deep ocean currents causes fibers to be trapped on the seafloor, as sediment settles out of the flows,” says Dr Ian Kane.

Overall, the team says its experiments demonstrate how these sediment flows have the ability to move huge amounts of plastic waste from close to shore into the deep sea. Understanding this distribution can help scientists understand why different types and sizes of plastic are consumed by different animals, something we are learning more about the consequences of all the time, and also shed light on how toxins build up on the ocean surface.

The research was published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Source: University of Manchester