Philadelphia University freshmen Charles Barilo, Peter Holderith and Zachary Samalonis were recently tasked with choosing a painting from those on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and creating a visual showpiece machine based on that painting which incorporated da Vincian thought processes. After a month of tinkering, they presented a cranked machine where sections of a topographical map are slowly raised when the handle is turned.

The painting selected for the Exploration Through Motion project was the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River by Thomas Moran. "From there we spent a week in ideation and thinking of different ways to bring the painting to life," explained Samalonis. "We picked an idea and began researching the terrain of the canyon and the different mechanisms that would bring it to life. After that we took a real topographical map and placed it in Adobe illustrator."

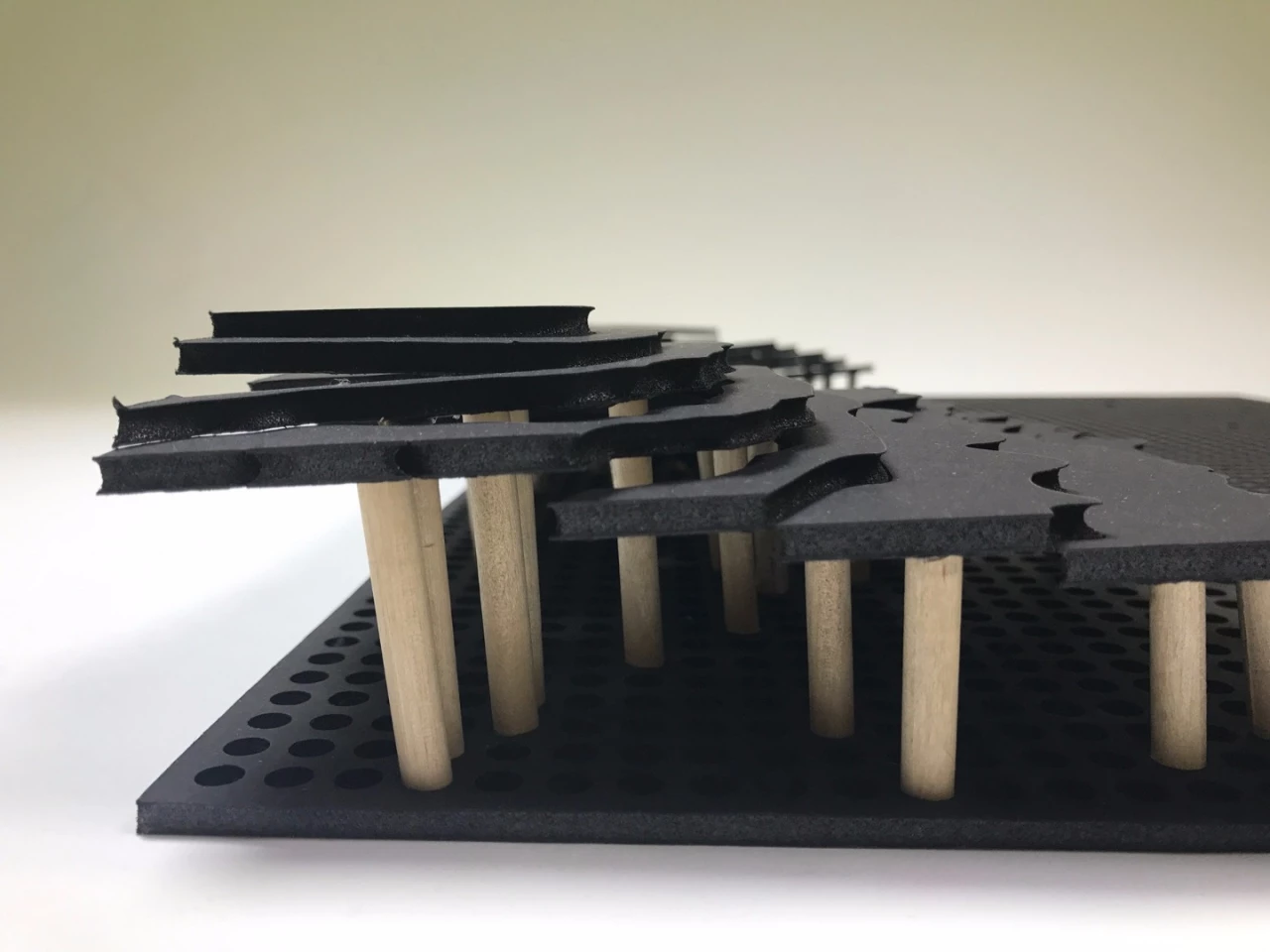

A "big ugly" foam test model was created to determine optimum locations for the dowels used to raise the shaped map platforms, followed by a wooden model. Early versions of the intricate laser cut map components proved troublesome – the overall effect looked great, but the jigsaw-like pieces didn't move in the way the team wanted. So a few layers and a bit of map detail were sacrificed to reduce friction between pieces.

At the same time, the team used Illustrator to design a set of paddle gears and cams that would be driven by a hand crank and slowly bring the topographical map to life. "We had to do the math and calculations to get the gear ratio and lift we wanted," revealed Samalonis.

More laser cutting followed, then the gears were mounted outside the CNC-cut box and the cams, which would push up a masonite platform that raised the dowels, installed inside.

After a few days spent assembling and a week of fine tuning, the construction was stained and presented to the University's Industrial Design Department.

"It was a cool experience because It was the first real presentation that my classmates and I had to get in front of a large crowd and present our work," Samalonis told us. "It also was cool opportunity to show the professors how the concept ideas became a reality. Something that Philadelphia University does different is they treat every project as a real world project. The professors become the clients and we present our ideas in 'client meetings.' As freshmen it gets our feet wet in what it's like to be working in the real world. So in the end it was really cool getting to see how the collaborations helped shape the final result. It is currently awaiting display somewhere on the university."

As you can see in the video below, the map starts off laying flat at the top of the box. Turning the crank starts raising sections landscape until, after 64 turns of the handle, the map is revealed in all its topographical glory. The highest layers stand 4 inches above the canyon bottom.

Source: Charles Barilo, Peter Holderith and Zachary Samalonis