Despite all you read about early car speed records, trains actually held the land speed record until 1907. That all changed when Glen Curtiss built and rode a V8 motorcycle to a land speed record of 136 mph.

Within a decade he would become the Henry Ford of the aerospace industry, but his motorcycle record of 1907 was not bested until 1930.

It was the only motorcycle to ever hold the outright land speed record and because the train records were powered initially by steam, and then by electricity, it was the first internal combustion engined invention of any sort to hold the outright land speed record.

In automotive terms it is the equivalent of the Antikythera mechanism and always seems to slip through the cracks when books are written about speed records, because they are usually only consider cars.

Our three-part history of the world's fastest cars project is underway and we've published the first part of the history (1946 to now) and we're currently working on the period 1890 to 1914.

This context is relevant to the story of Glen Curtiss, because across the history of the highly contested endeavor of going faster than anyone ever has before, Curtiss left an indelible mark – yet it was only ever a sideline business for him.

Curtiss' subsequent role in the history of aviation overshadows some of his most remarkable achievements along his path to greatness.

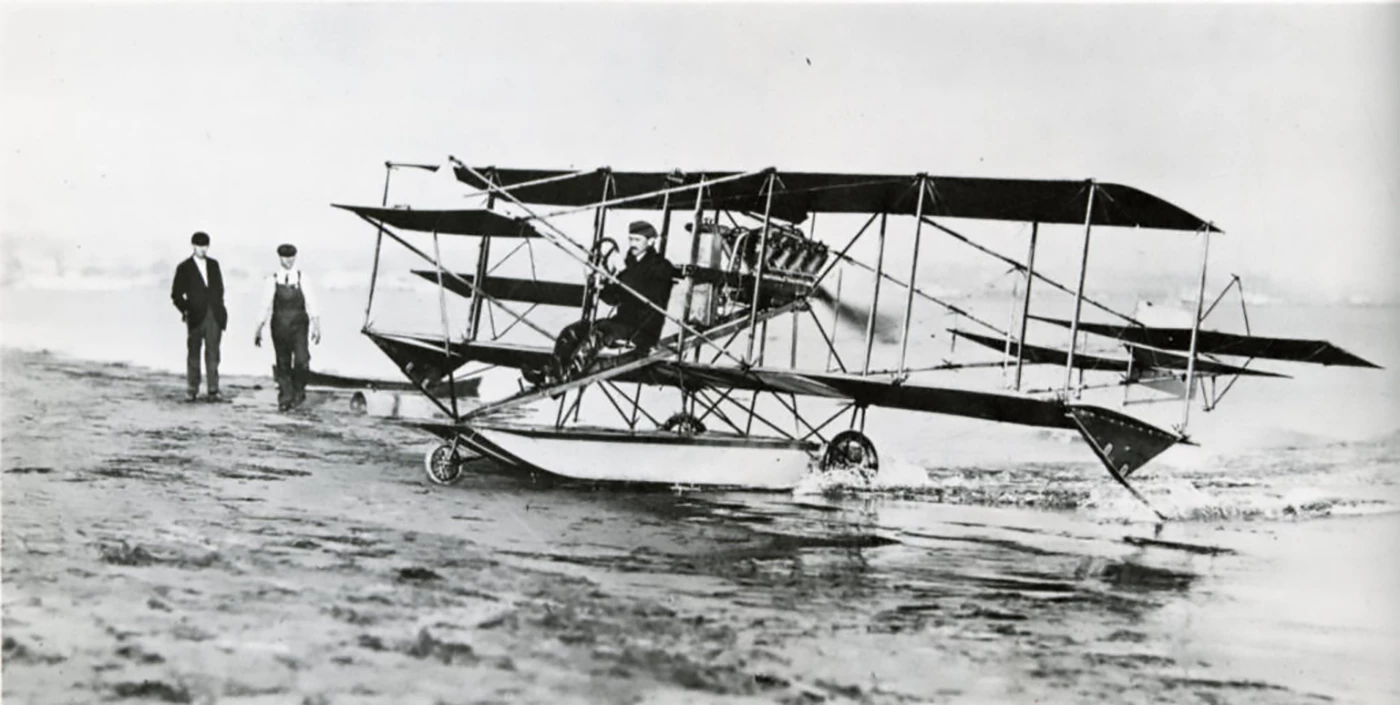

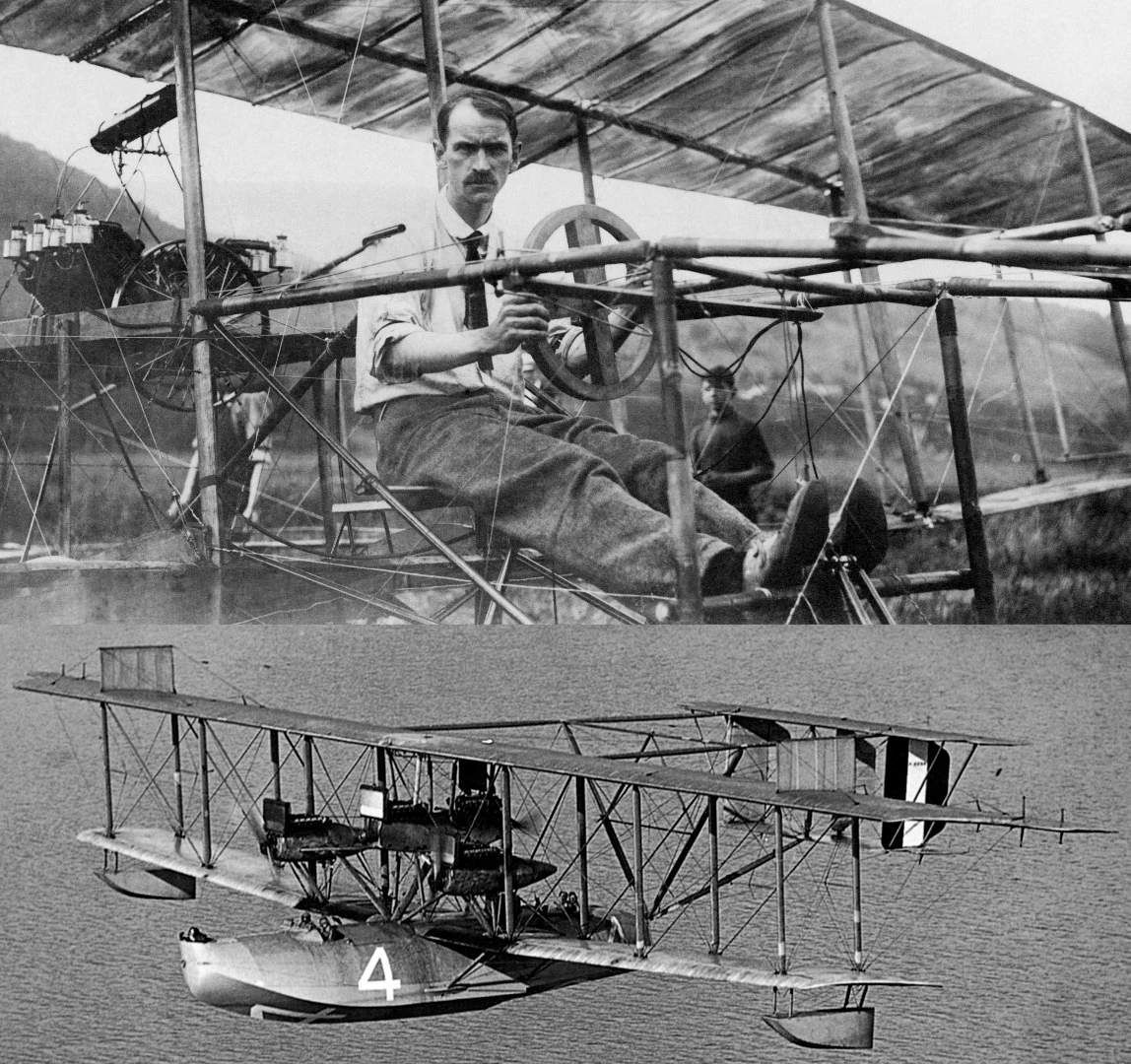

He was one of the great aviation pioneers and is generally regarded as the father of naval aviation through his work with sea planes. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross as a civilian and the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company became the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world during World War I, producing 10,000 aircraft during the war, with Curtiss both Chairman and President.

When it floated in 1916, it employed 21,000 people. In 1929, Curtiss-Wright was formed by the merger of companies founded by Glenn Curtiss and the Wright brothers.

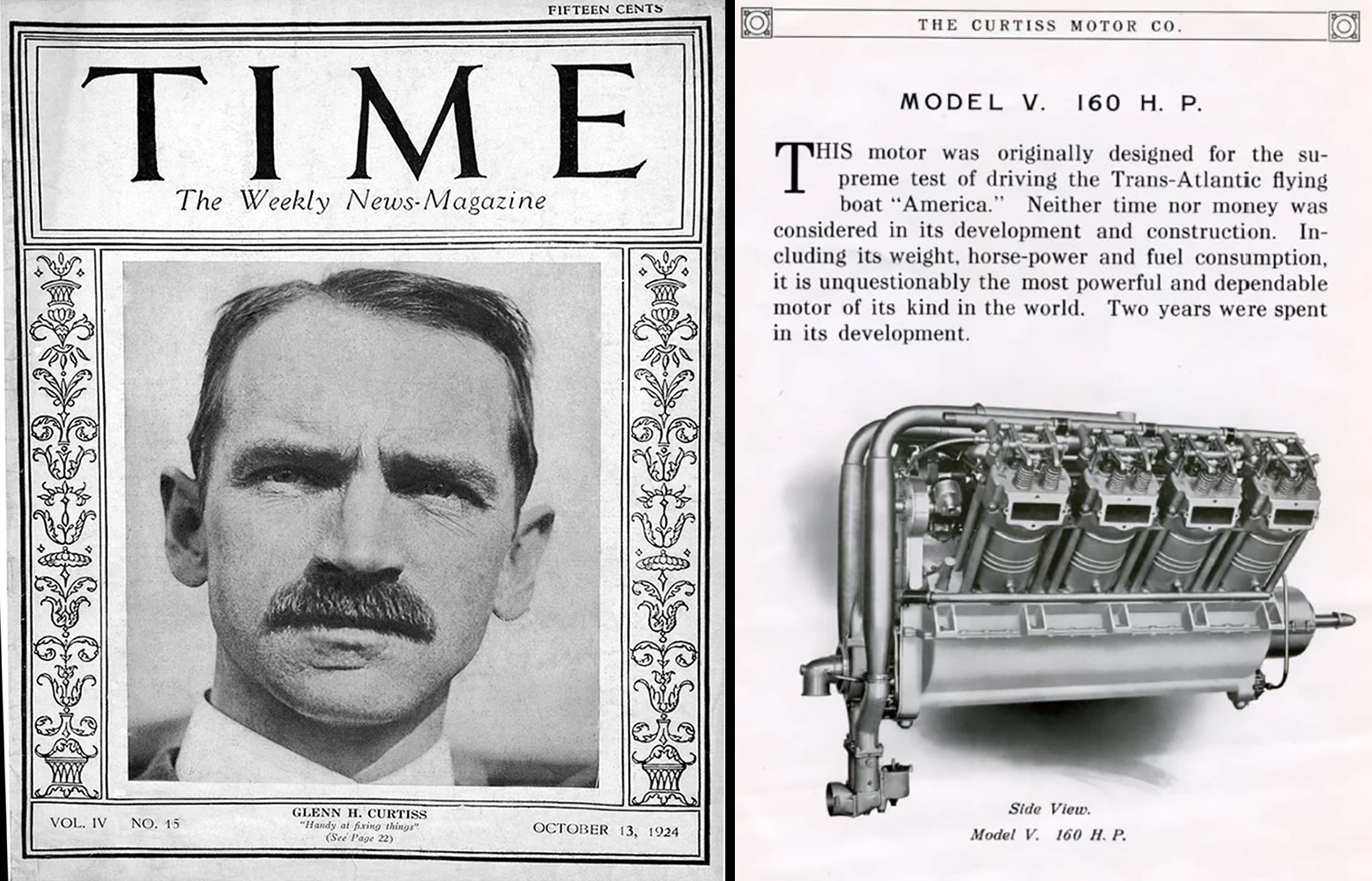

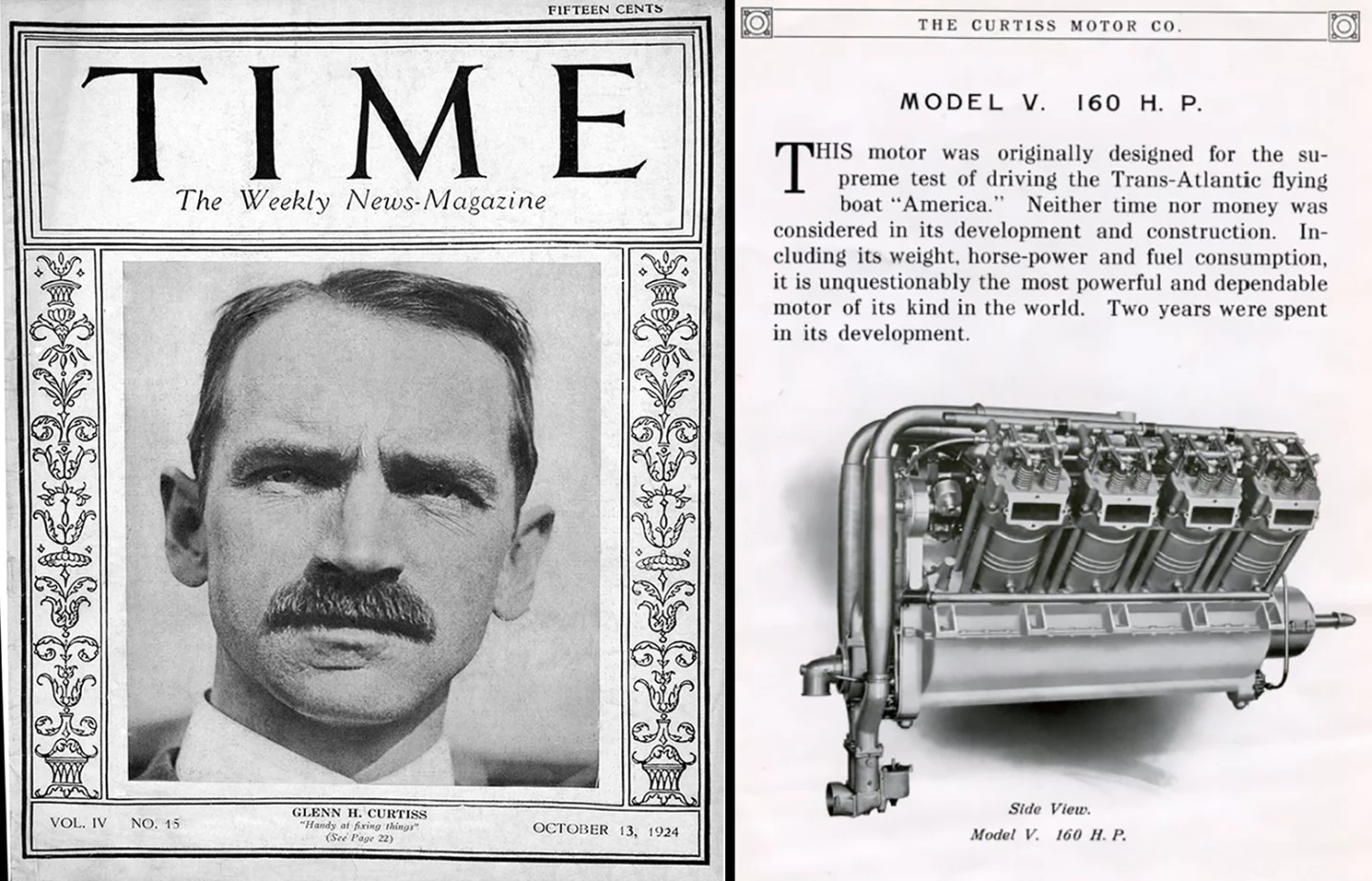

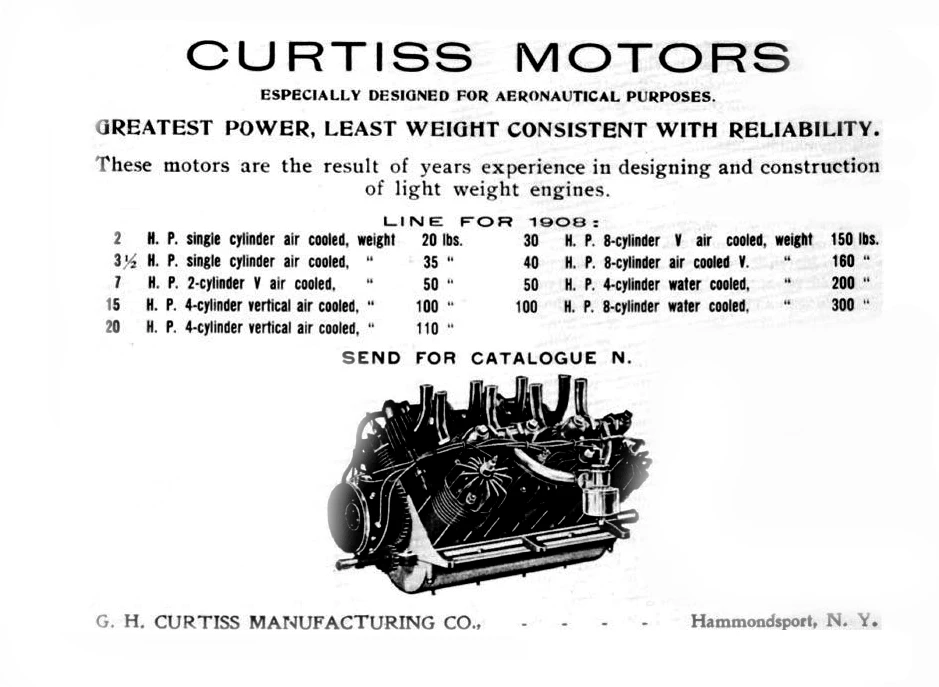

As an aviator Curtiss was so significant he made the cover of Time magazine, but he was primarily an ingenious engineer, and his initial main business was the manufacture of high-power, lightweight engines for a range of purposes, as can be seen from the advertisement below.

He produced engines and manufactured motorcycles under his own brand, and realised that the low weight and minimal frontal area of the motorcycle offered an easy way to demonstrate his wares to the public and sell more of his engines.

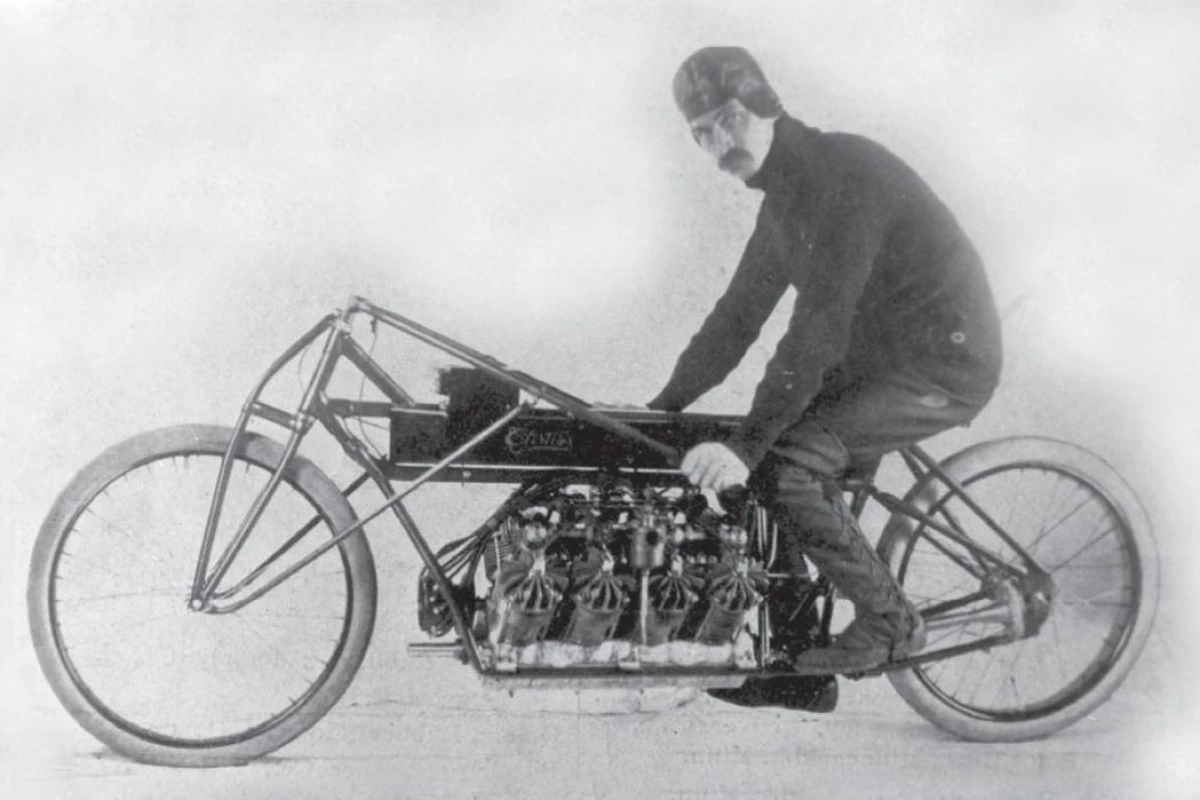

This is where his self-belief really begins to raise him above the rest of the greats. He not only designed engines, motorcycles and aeroplanes, he was also the test pilot, and he was also in the saddle of the motorcycles which set land speed records in 1903 and 1907.

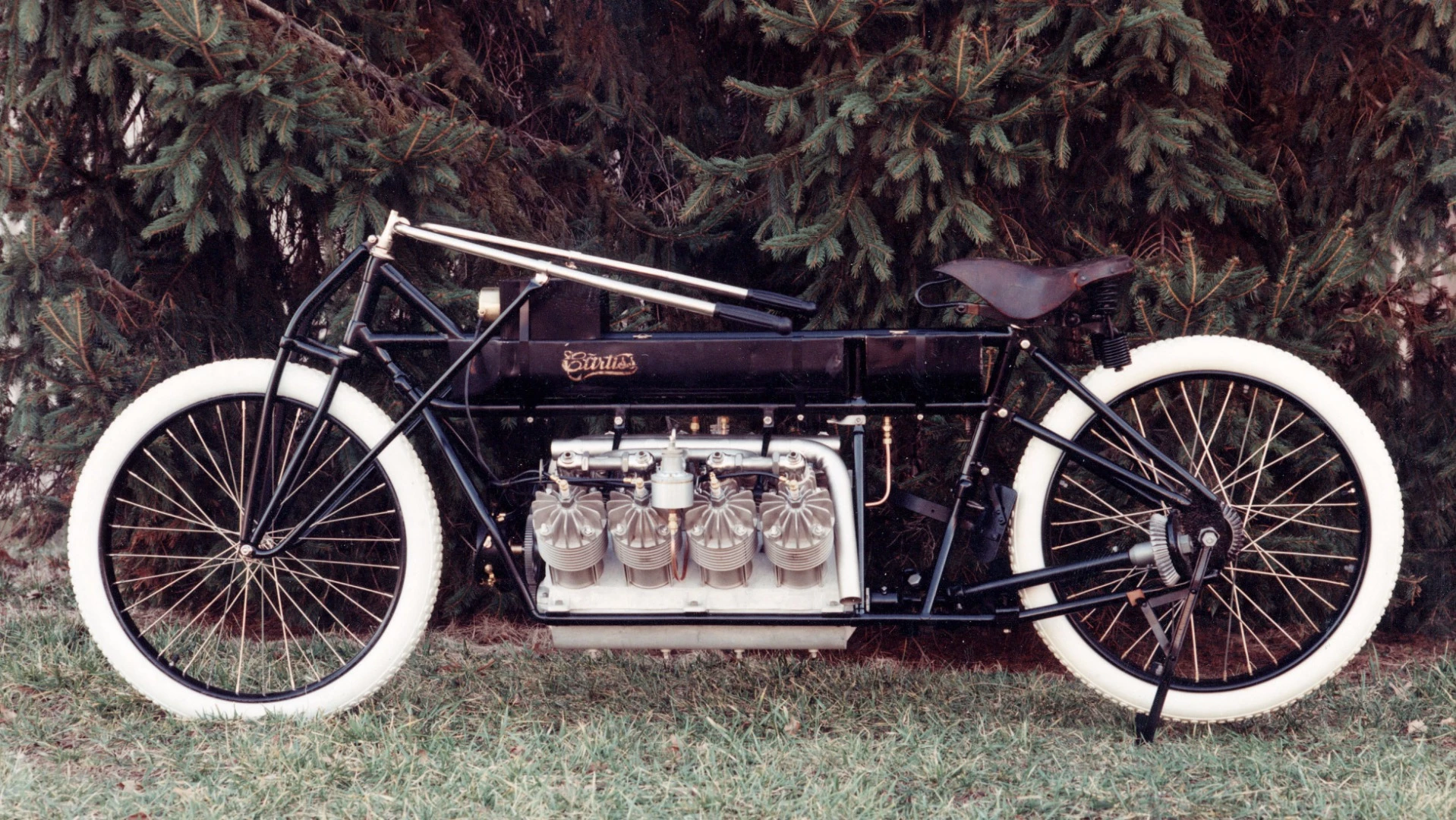

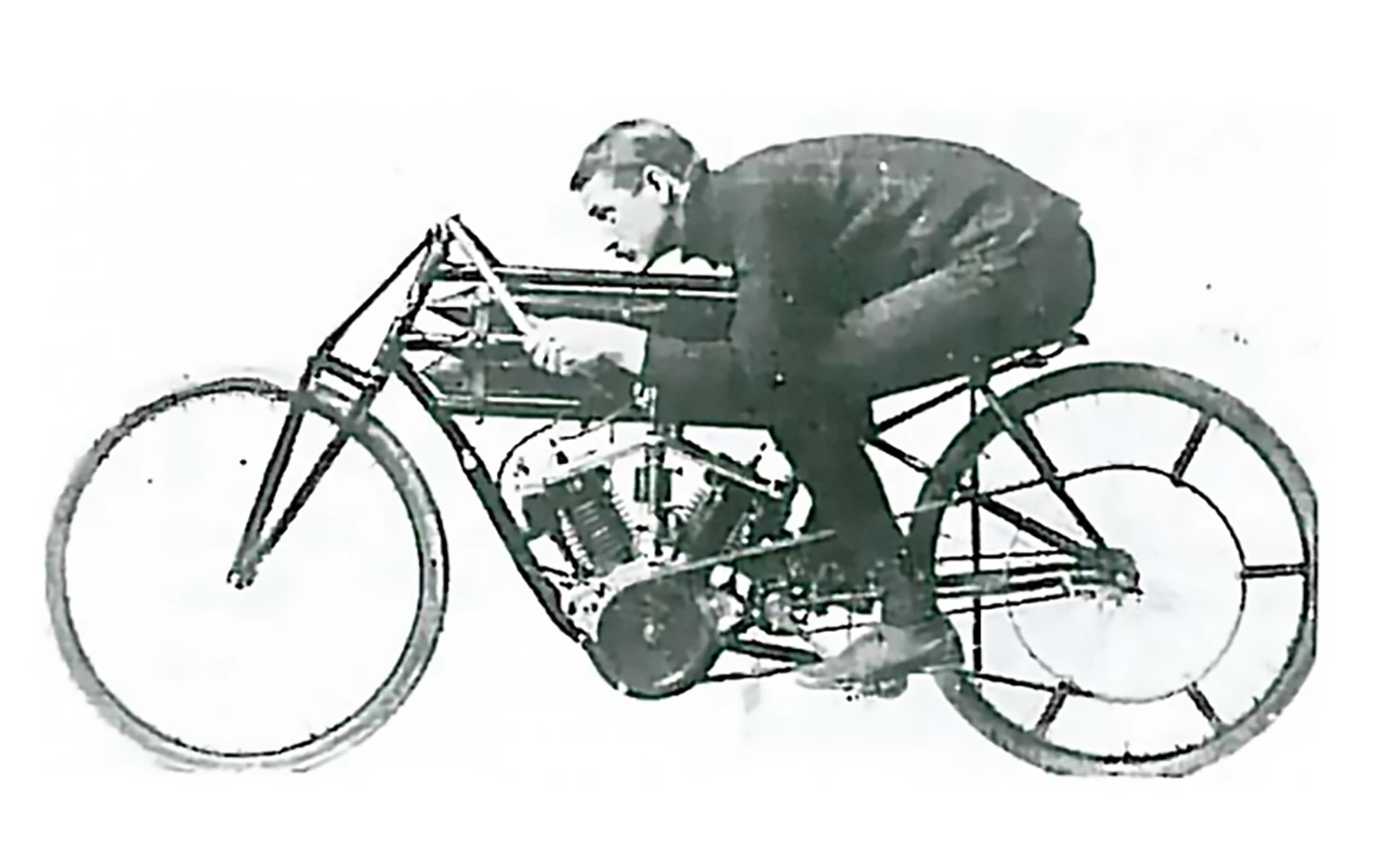

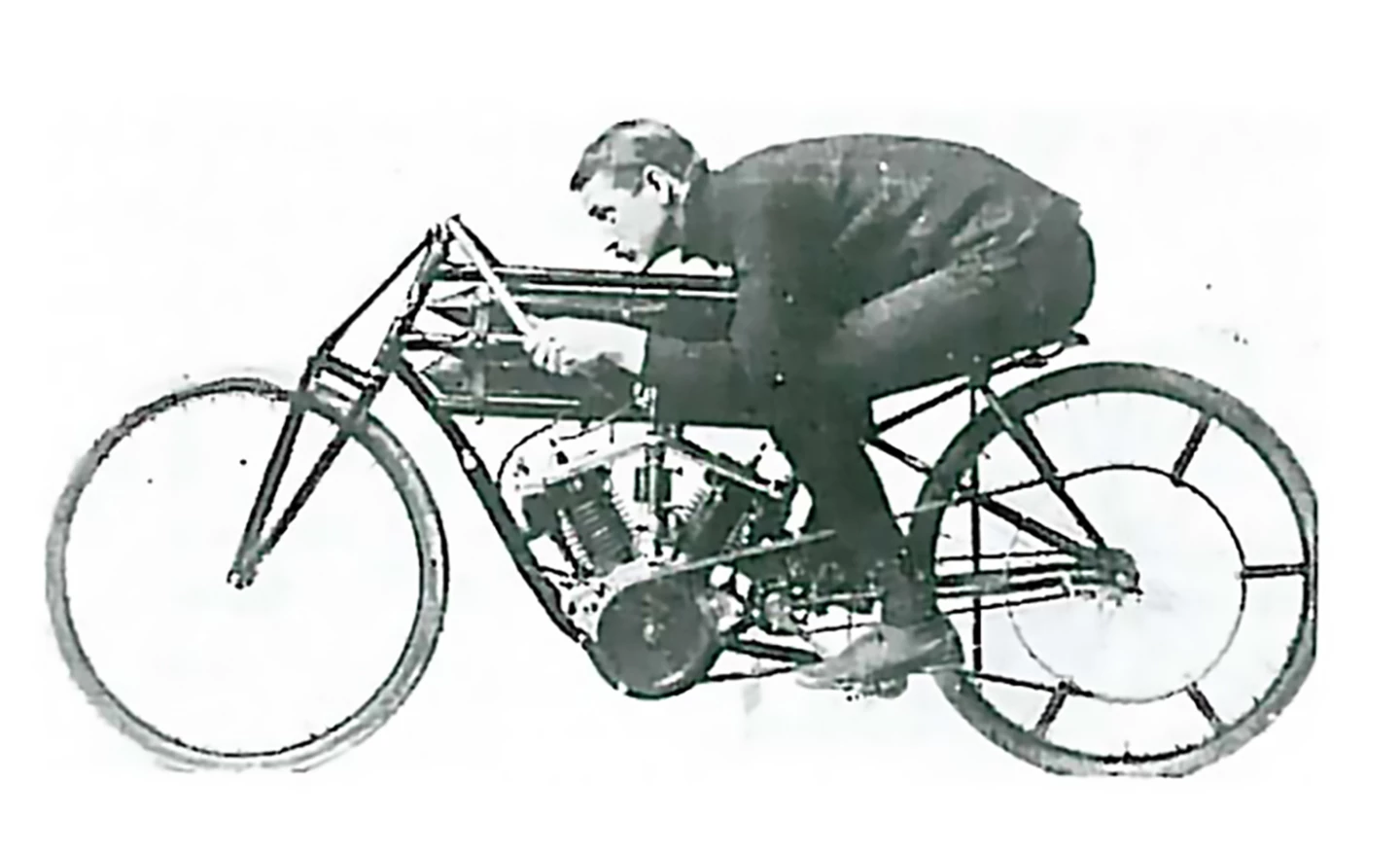

In 1903 he was timed at Yonkers (New York) riding his own Curtiss Hercules 1000cc v-twin at 64 mph (103 km/h), earning him a place in history as the first motorcycle speed record holder. That's Curtiss on the speed record bike above, complete with twin pointy gas tanks, and that's a 1906 Curtiss 1000cc v-twin below, earlier models of which would have formed the basis of the record breaker.

To put this achievement in perspective, it's worth noting that the record breaking bike was built a decade prior to the Harley-Davidson v-twin going into series production.

There's some nice pics of the road bikes upon which the initial record breaker was based in the image library for this story, and if you head on over to the Vintagent, you'll see a pic of Curtiss' radial three-cylinder motorcycle – quite a treat.

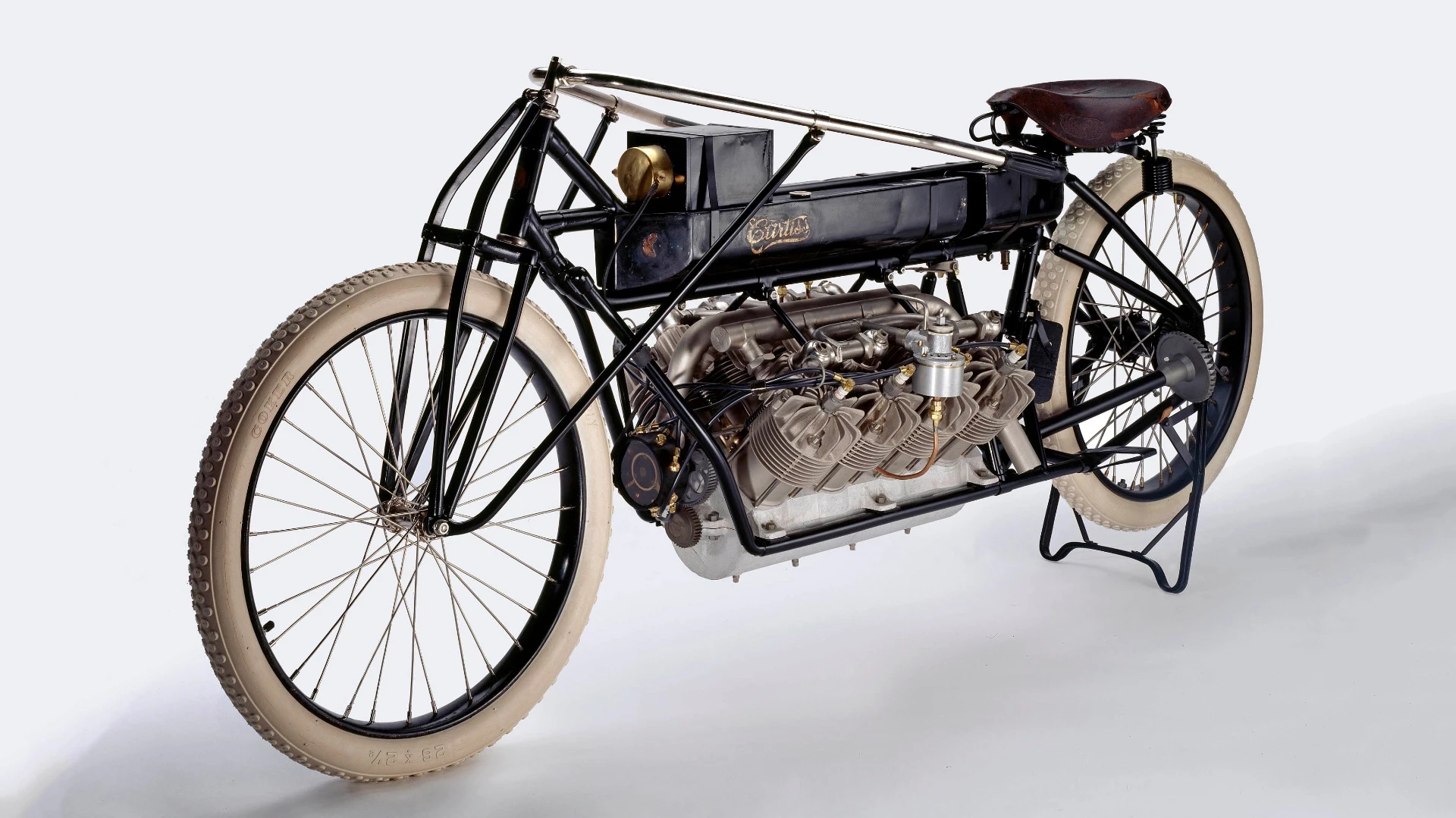

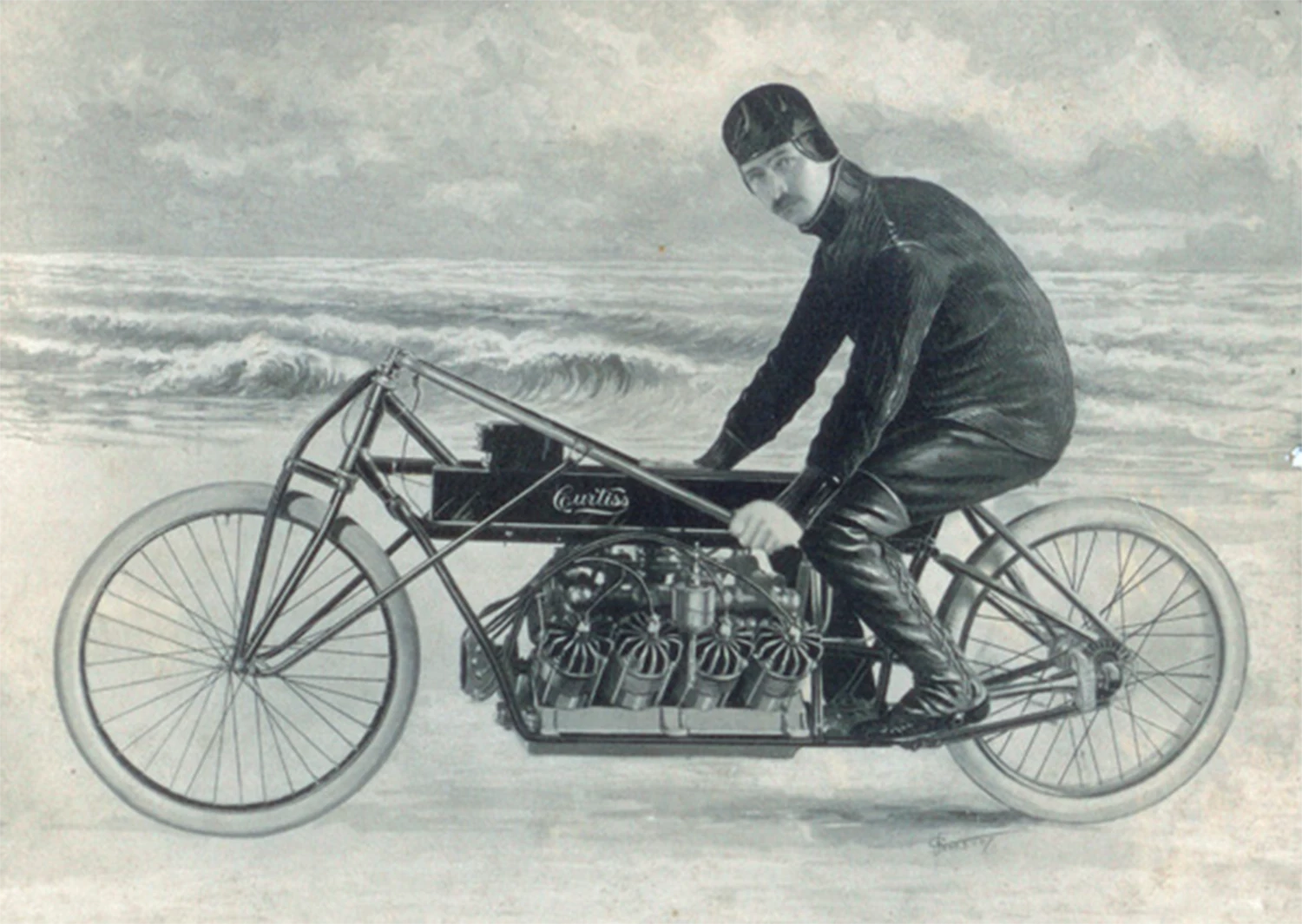

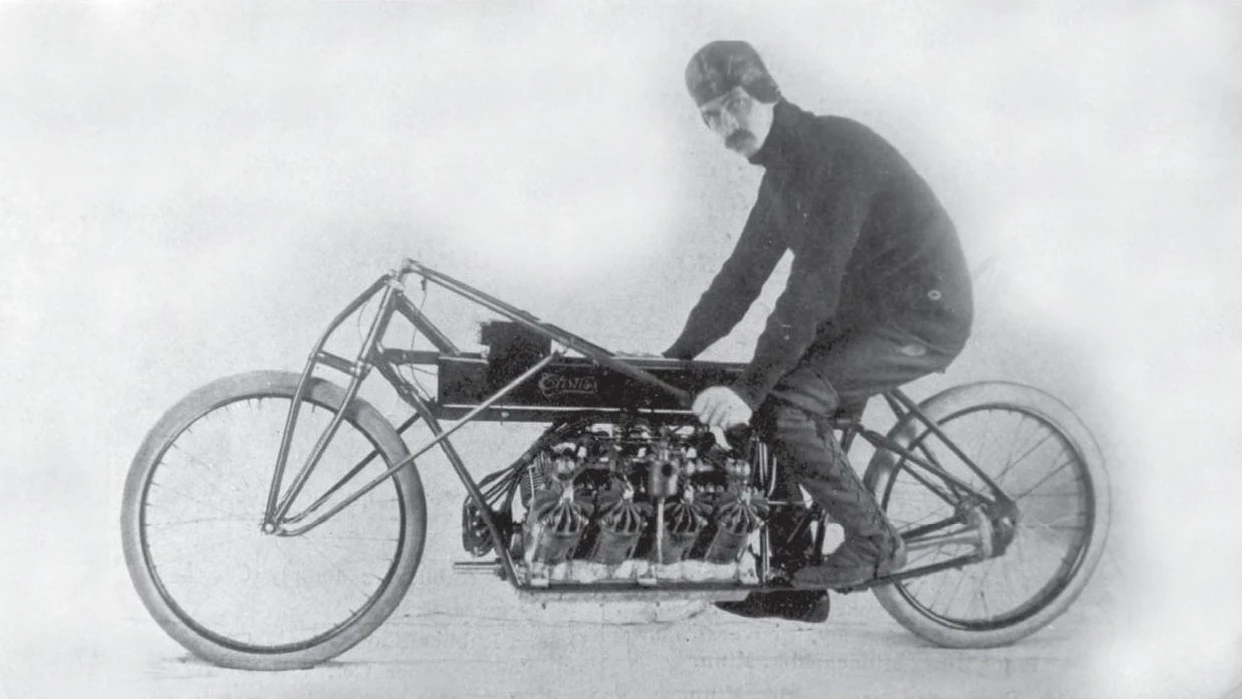

As his engines grew more powerful and reliable, Curtiss wished to prove their worth as a lightweight power unit via the media, so he installed one of his 4000cc V8 aircraft engines (essentially four of his v-twins on a common crank), into a motorcycle and blew all competitors into the weeds with a run of 136.27 mph (219.31 km/h) on 24 January 1907 during the premier speed event in the world at that time, Speed Week in Ormond/Daytona Beach, Florida.

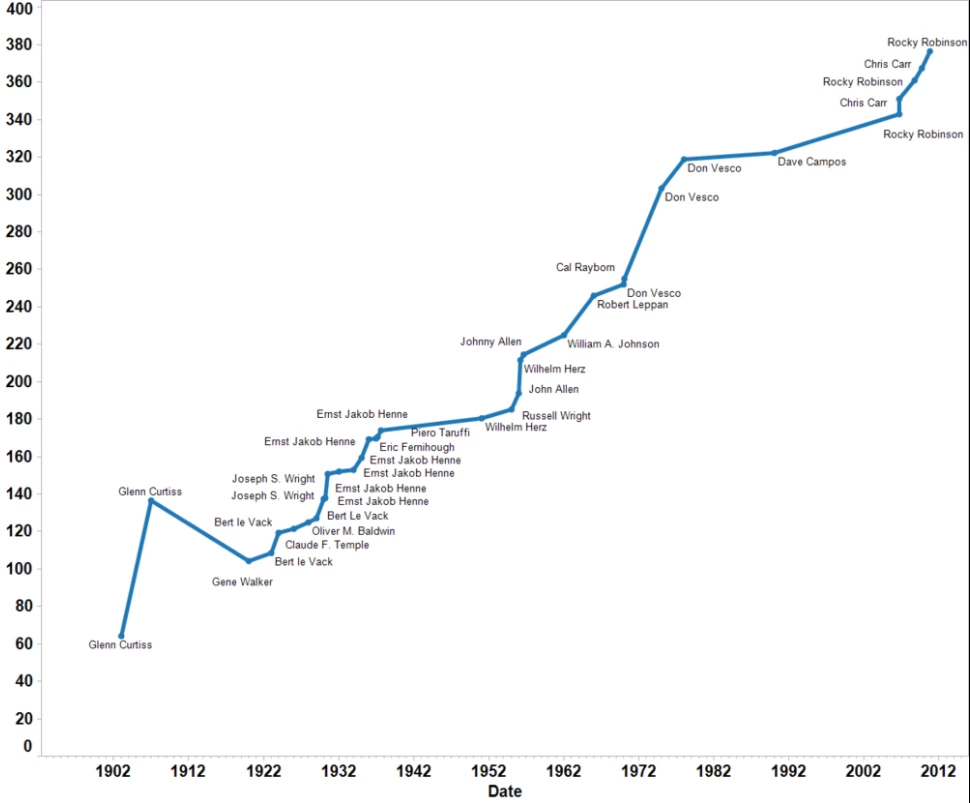

Those are the first two data points on the graph above, showing the progress of the motorcycle speed record from 1906 onwards. You can see Curtiss was decades ahead of his time.

Indeed, so powerful and fast was the Curtiss V8 that it took another 23 years before it was beaten in 1930 by Joseph Wright's OEC Temple JAP at 137.23 mph (220.99 km/h).

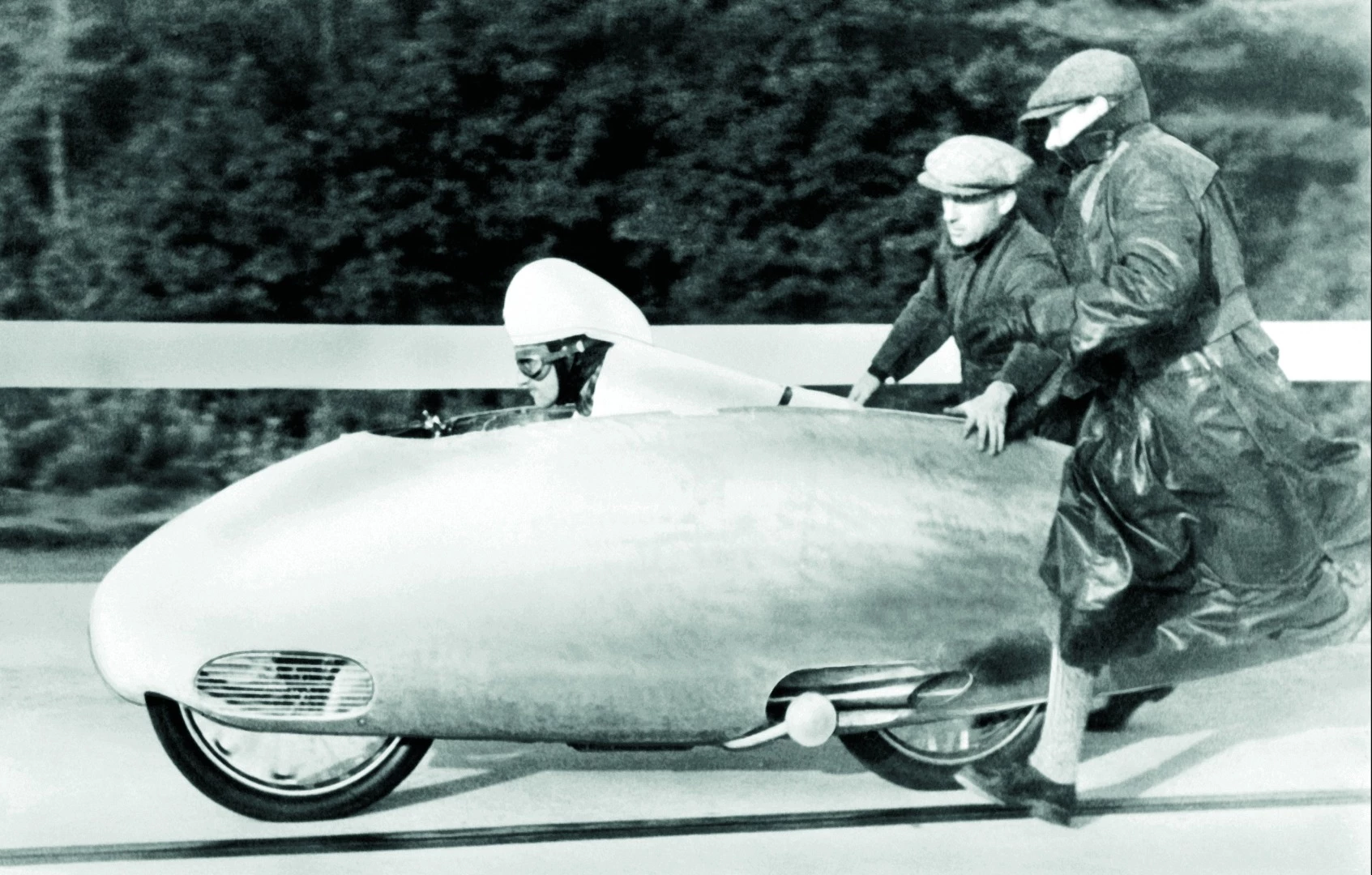

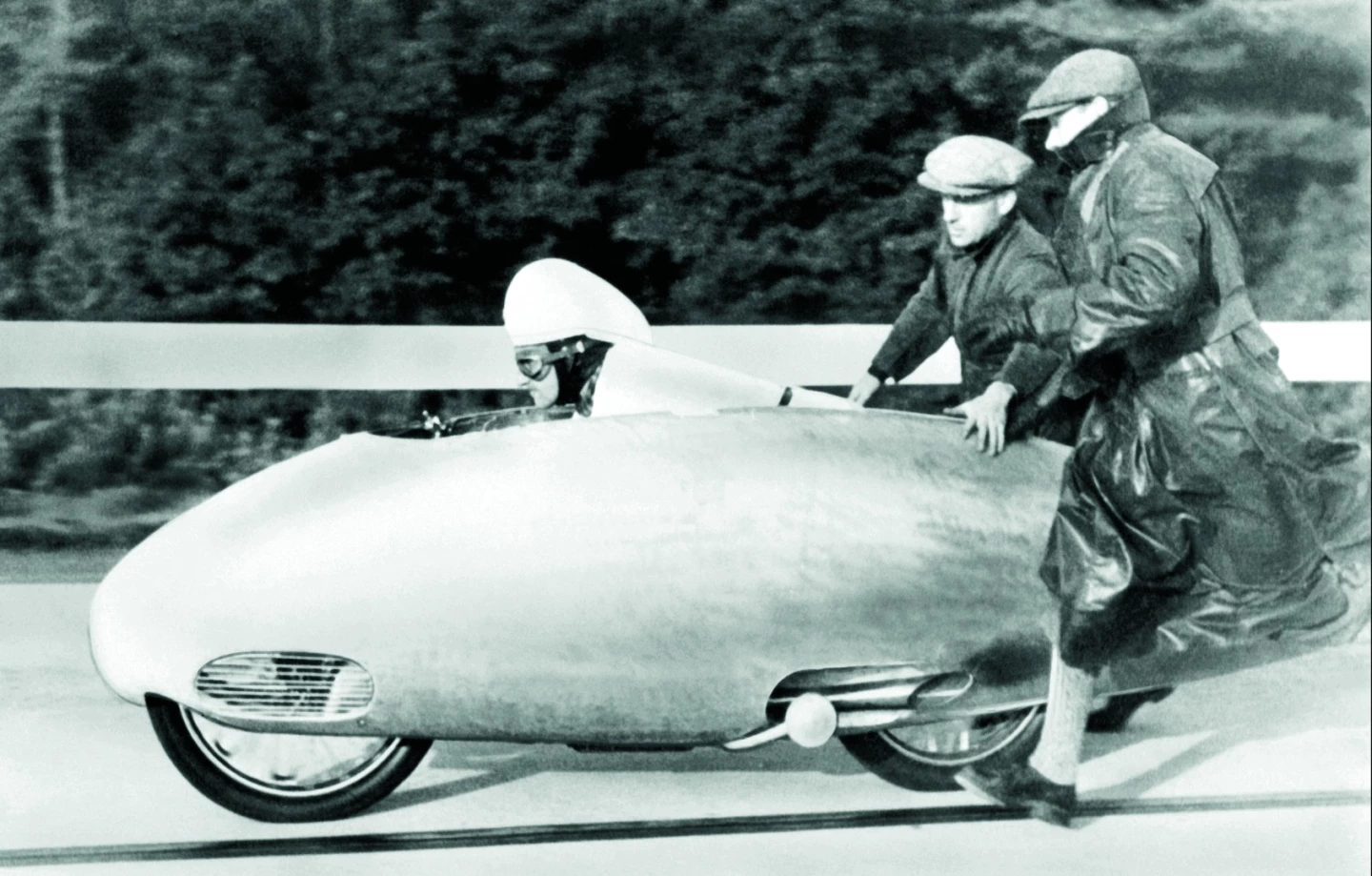

Within weeks, BMW rested the crown with a run by Ernst Henne of 137.74 mph (221.67 km/h) and the combined forces of BMW saw Henne better the record every year until 1937. But that was a quarter century after a world war had catalyzed technological development in every facet of aerodynamics and engine development.

The wind-tunnel streamlining evident on Henne's BMW and BMW's mastery of supercharging engines had changed the game.

Take a moment to compare the motorcycles in the two images – from a leather flying helmet to an aerodynamic helmet, Curtiss' run of 136 mph in January 1907 defied the laws of physics as much as we understood it back then.

Fast trains, circa 1900

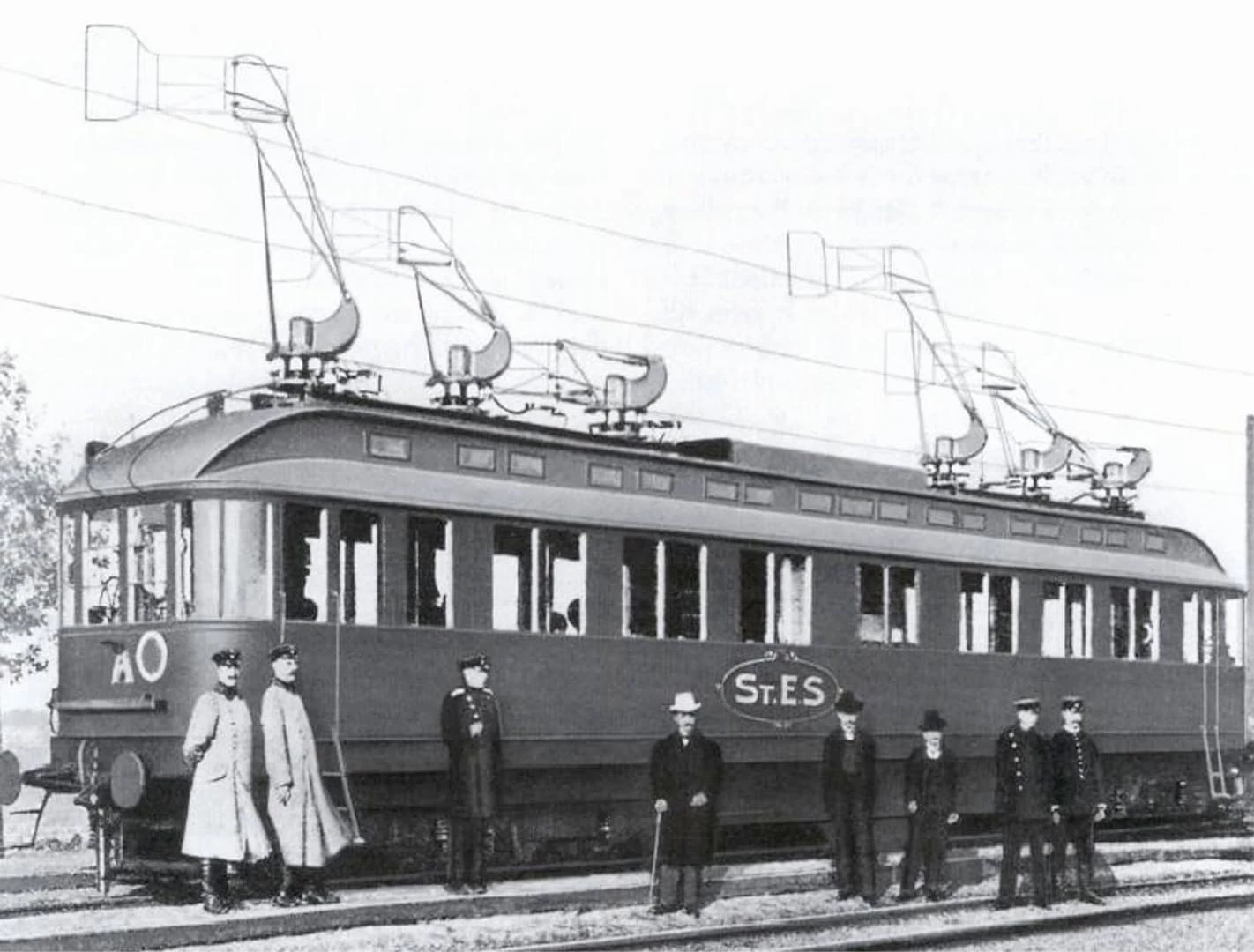

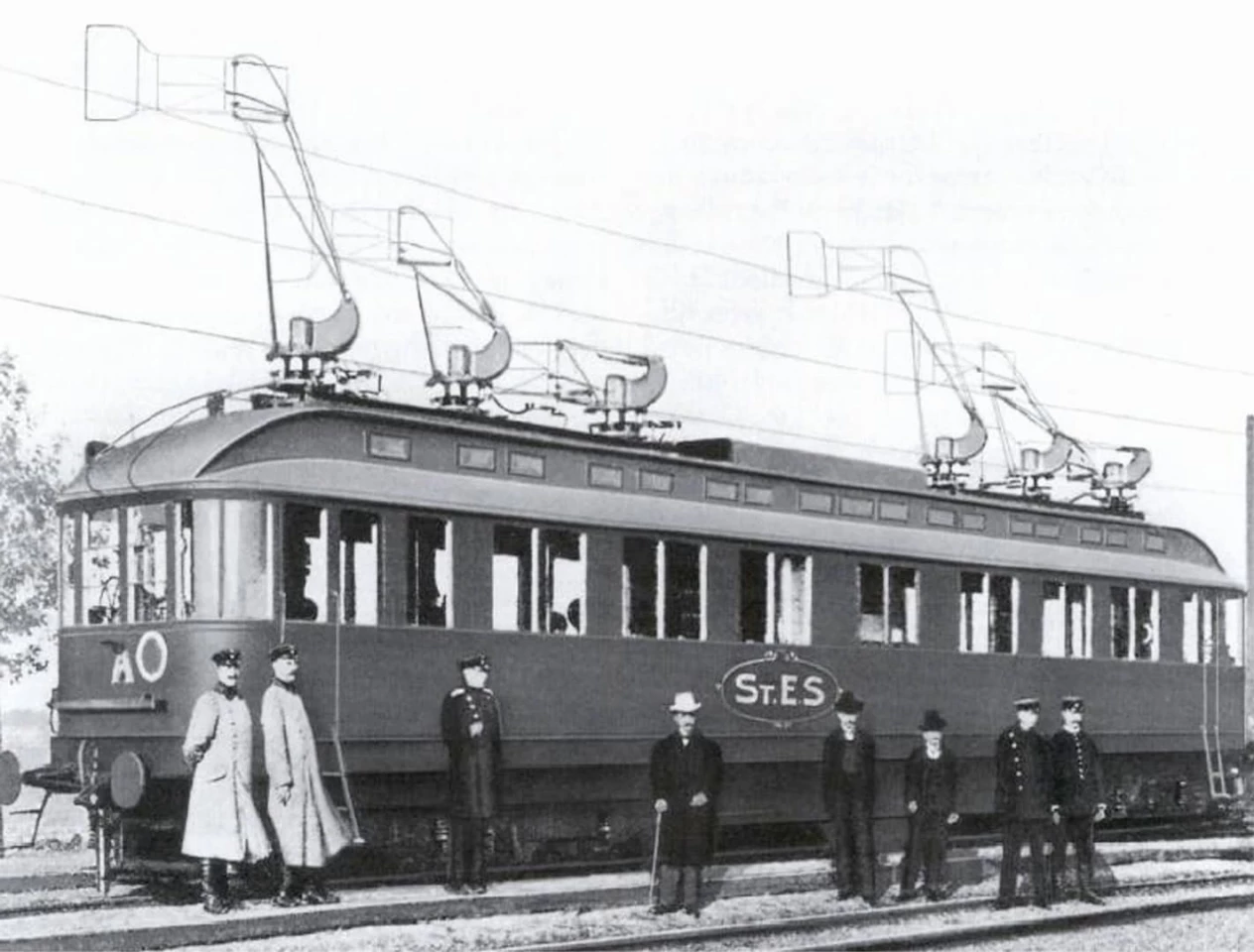

More importantly, the automotive industry was still in its infancy, and trains had always been faster than cars and motorcycle until that point, with the world land speed record actually held by an experimental electric trolley car, though automotive circles tend to ignore the record.

In 1902, a 23 km section of electric rail infrastructure was created from a military railway by the German Society for the Study of Electrical Rapid Transit, a consortium led by General Electric, Siemens & Halske, the industrial giant Krupp and several major German banks.

Located between Marienfelde and Zossen, the test track played host to two competing electric drive systems for the 50-person trolley cars that were constructed - one railcar was fitted with three-phase AC electrical equipment supplied by AEG and the other with similar equipment supplied by Siemens & Halske. Both vehicles exceeded 124 mph (200 km/h), with the Siemens & Halske railcar setting an initial record of 126 mph (203 km/h) and eventually reaching 128 mph (206 km/h). On 28 October 1903, the AEG railcar was timed at 130.7 mph (210.3 km/h), a new absolute land speed record.

Just a few days later, on 5 November, 1903 Arthur Duray pushed the automobile record to 84.73 mph (136.36 km/h) driving a Gobron-Brillie, so cars were clearly still a long way behind railed transport in terms of speed.

Numerous records were set in the next few years with the automobile speed record climbing to 121.57 mph (195.65 km/h) on 29 January, 1906 when the famous Stanley Steam Company streamliner set a new benchmark on the sands of Daytona Beach, Florida.

Then, in 1907, Curtiss rolled up at Daytona and became the first non-railed vehicle to hold the land speed record.

The Curtiss V8 which held the unofficial world record until 1930 is resident in the Smithsonian, and an exact replica has been created for the Curtiss Museum.

Glen Curtiss. We salute you!