Once confined to Latin America, Chagas disease – a potentially deadly parasitic infection that is spread in a gross way – is now endemic in the United States, threatening both humans and their pets in what experts are calling a silent public health crisis.

In September 2025, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published an article in which it raised concerns about a rise in cases of Chagas disease and why the disease, once confined to Latin America, should now be considered endemic to the United States.

The main vector, or “spreader,” of Chagas is the cutely named kissing bug, or triatomine bug, which is found in 32 US states, mainly across the southern half of the country. Any semblance of cuteness ends with the name. Transmission occurs when the bug bites exposed skin – often the face or arms – and defecates near the bite. The feces, contaminated with the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, enter the body through mucous membranes or skin breaks. The parasite can also be spread orally, through blood or blood products, and organ transplantation.

Chagas affects not only humans, but also a wide range of animals, both domestic and wild. Dogs, in particular, are significant domestic reservoirs, often contracting the disease before their owners realize it’s circulating locally. As a wildlife and public health veterinarian, Dr Brad Ryan works at the intersection of human and veterinary medicine and has had first-hand exposure to Chagas disease.

“These kissing bugs, these triatomine bugs, don’t discriminate,” Ryan explained in an interview with New Atlas. “I mean, I was reading that they can infect other insects, even. They can infect other crickets. They can infect amphibians. A lot of wild mammals. So they’re just looking for blood.

“The transmission [of T. cruzi] can occur through the bite, and that’s what makes them interesting, but it’s also what makes them so disgusting: they bite you and then they defecate in your wound. And, of course, that’s itchy; it can cause an allergic reaction, so we just start scratching it, just like we would a mosquito bite. And we have the potential to put that parasite into our body. Dogs can also get these [infections] just because they see an insect moving, and they eat the bug.”

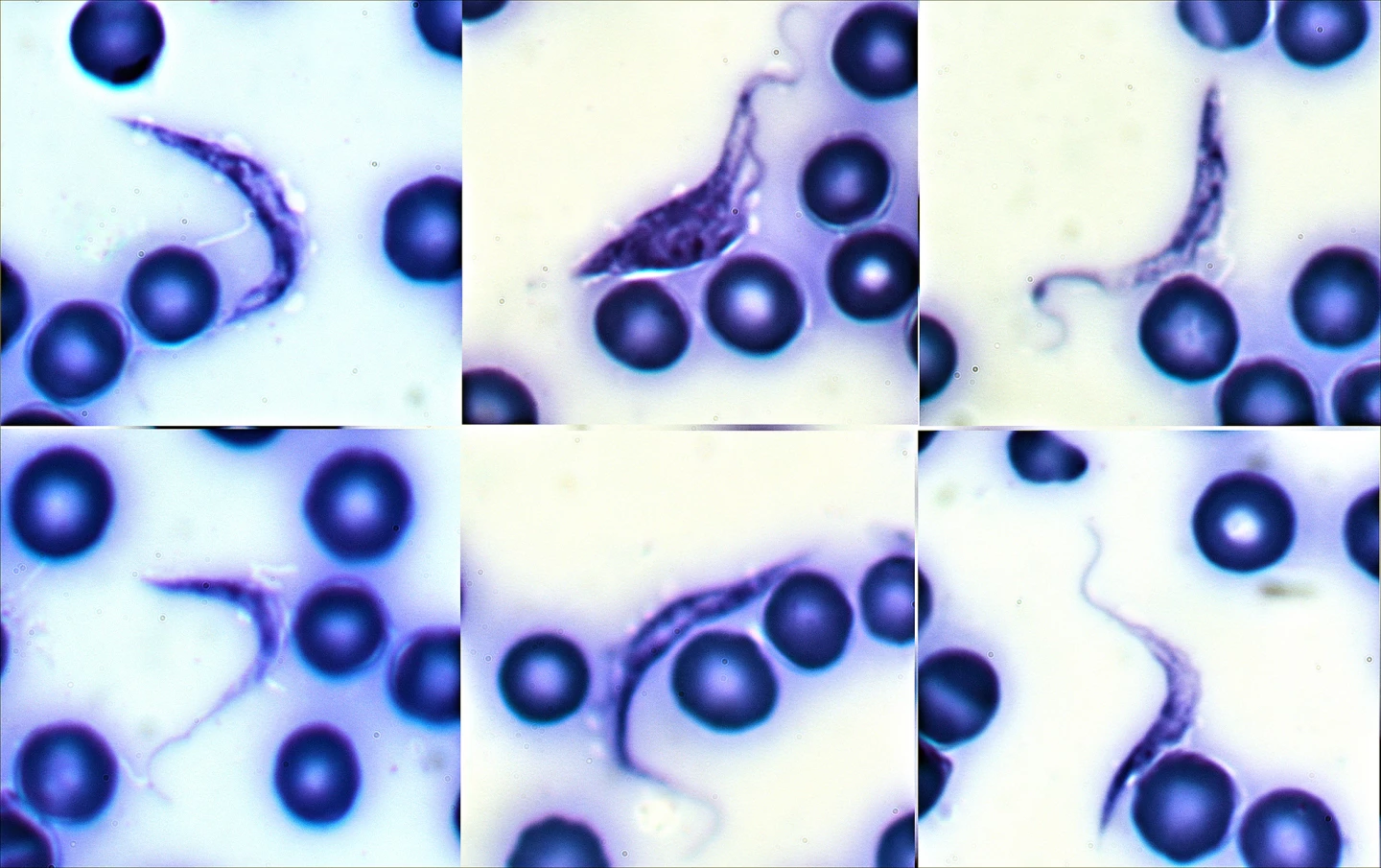

Once it’s inside the body, T. cruzi invades a variety of host cells, particularly those lining blood vessels and the muscle cells of the heart and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The parasites multiple within these cells, eventually reaching numbers high enough to cause the cells to rupture, releasing large quantities of the parasite into the bloodstream. This cycle of invasion, replication, and cell destruction underlies many of the tissue damage and inflammatory responses seen in Chagas disease.

The disease has two main phases: acute and chronic. In humans, the acute phase often goes unnoticed because it is either asymptomatic or causes only mild, nonspecific symptoms. When they do occur, these may include fever, fatigue, enlarged lymph nodes, localized swelling at the infection site, or swelling of one eyelid (called Romana’s sign).

In dogs, the acute phase is also frequently subclinical. When clinical signs do appear, they are usually the result of the immune system’s response to the parasite. Common signs can include fever, lethargy, loss of appetite, enlarged lymph nodes and spleen, pale gums (resulting from poor circulation), and sometimes vomiting or diarrhea.

If the parasite isn’t cleared during the acute stage, which is the case in the vast majority of infections, T. cruzi enters a chronic phase that can remain silent for years or even decades. During this period, parasite numbers in the bloodstream fall to undetectable levels, but the organism continues to hide and persist within tissues, particularly the heart muscle and, in humans, the GI tract. The body’s ongoing inflammatory response to these infected cells, coupled with direct tissue destruction from repeated cycles of parasite replication, leads to progressive organ damage.

In humans, the chronic phase of Chagas disease is often divided into two forms:

- Indeterminate (asymptomatic) stage. Most people remain symptom-free for many years after initial infection. The parasite is present but doesn’t yet cause noticeable damage.

- Chronic symptomatic stage. In around 20% to 30% of cases, persistent infection eventually causes significant disease, most often affecting the heart. The hallmark complication is cardiomyopathy, a form of heart muscle damage that can lead to arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), heart enlargement, congestive heart failure (fluid accumulation), thromboembolic events such as strokes, and sudden cardiac death.

In some chronic human cases, the parasite also damages the autonomic nerves controlling the GI tract. This can lead to megacolon or megaesophagus, causing severe constipation, difficulty swallowing, malnutrition, and secondary infections.

The chronic phase in dogs shows many parallels to human disease, but often progresses more rapidly, appearing three weeks post exposure. Once heart tissue is significantly damaged, dogs develop chronic myocarditis (inflammation of the heart muscle), which leads to a range of potentially fatal cardiac complications, including cardiac arrhythmias and electrical conduction abnormalities, congestive heart failure, an enlarged heart visible on imaging scans detected during examination, and syncope (fainting) due to poor blood flow.

Unlike humans, dogs rarely develop GI complications, though secondary effects from heart disease, such as reduced blood flow to other organs, can occur. Because dogs often experience a more aggressive form of chronic Chagas, sudden death may be the first and only sign of infection, particularly in working dogs. What is clear is that an owner’s concern for their dog is likely what causes them to visit a vet.

“Clinical signs are going to be the main way that we diagnose this, unfortunately,” said Ryan. “Oftentimes, we connect these dots when they’re sick. So the clinical signs that I would be looking for – and this is where it gets tricky, because there are a lot of diseases that can present this way – and, so, weakness, lethargy, a pet that’s collapsing, and signs of congestive heart failure.”

Diagnosing Chagas disease can be a challenge in both species, but for different reasons. In humans, the difficulty stems from the disease’s long, silent incubation and the fact that early symptoms are often mistaken for a flu-like illness or other minor infection. During the acute phase, diagnosis is usually based on direct detection of the parasite in the blood, often through microscopic analysis or PCR (polymerase chain reaction) testing, when parasite levels are still high. Once the disease enters the chronic phase, the parasite retreats into tissues, making it far harder to detect. At that stage, diagnosis relies on detecting antibodies against T. cruzi in the blood.

In dogs, the diagnostic picture is similar but often more complex. Many infected animals show no signs until irreversible heart damage has occurred, and by then, parasite levels in the blood are usually too low for conventional tests. Historically, this has meant that many canine infections went undiagnosed.

However, advances in veterinary diagnostics are beginning to close this gap. Antech Diagnostics’ advanced vector-borne disease (VBD) screening panel includes PCR-based testing capable of detecting T. cruzi DNA even at low levels, enabling earlier diagnosis. And any American vet can request the test.

“This is not a screening test,” said Ryan, who also acts as Antech’s Senior Professional Services Veterinarian. “And so, the PCR panel exists in its current form – we have a canine version and a feline version – and that exists because when pets are sick, and whether we know that there was exposure to certain biting insects, vectors, or there are clinical signs there that fit the bill.

“I mean this [Chagas disease] is an outlier, because almost all of them are going to be either mosquito or tick, and then we have these kissing bugs in their own category. In many cases, people can say, ‘Yeah, I saw that thing, I’ve seen those in my house, I’ve seen those around my house,’ right? And so, there are going to be different pieces of information that a doctor or a veterinarian is going to hear that would make them say, ‘I need to run something that’s more comprehensive.’”

Ryan firmly believes that what’s needed is education and to raise awareness so that the possibility of Chagas disease is at the forefront of people’s minds.

“I think everybody would agree that you can never have too much education,” he said. “And that’s the foundation here. We want doctors to be informed, we want veterinarians to be informed, and we also want the general public to be informed, so they can advocate for their own health and for their pet’s health as well.

“The whole reason I went to vet school and did my MPH [Master of Public Health] at the same time is because I really do believe in a One Health approach to medicine. One Health is an acknowledgement that, you know, you’re a mammal, I’m a mammal, and we’re all animals at the end of the day, and we have this shared environment.

“People are on the move, people relocate with their animals. We have wildlife that is constantly moving, and they can move pathogens around. And so, the more that we can open up dialog across the different medical sciences, the more we can learn from each other, and we’ll have a heightened awareness that, at the end of the day, allows us to have a win-win.”