Noisy knees after an ACL injury may raise fears of impending arthritis, but new research shows that these noises signal existing damage and not future decline, helping patients and clinicians separate worry from real risk.

Many of us are accustomed to noisy knees and the creaking, grinding, cracking and popping sounds that can accompany everyday life. Previous research found that noisy knees in adults aren’t necessarily a bad thing, but could be linked to osteoarthritis (OA). But what about noisy knees –referred to as crepitus in medical circles – in those who are younger?

A new study led by La Trobe University examined the association between knee crepitus in young adults following a traumatic knee injury and OA, to see if there was a link.

“We found that those with knee crepitus demonstrated more than two and a half times greater rates of full-thickness cartilage defects in the kneecap area, with more pain and poorer function early on,” said La Trobe graduate researcher and physiotherapist Jamon Couch, the study’s lead author. “But over the next four years, those with crepitus did not experience worse pain and function compared to those without knee crepitus.”

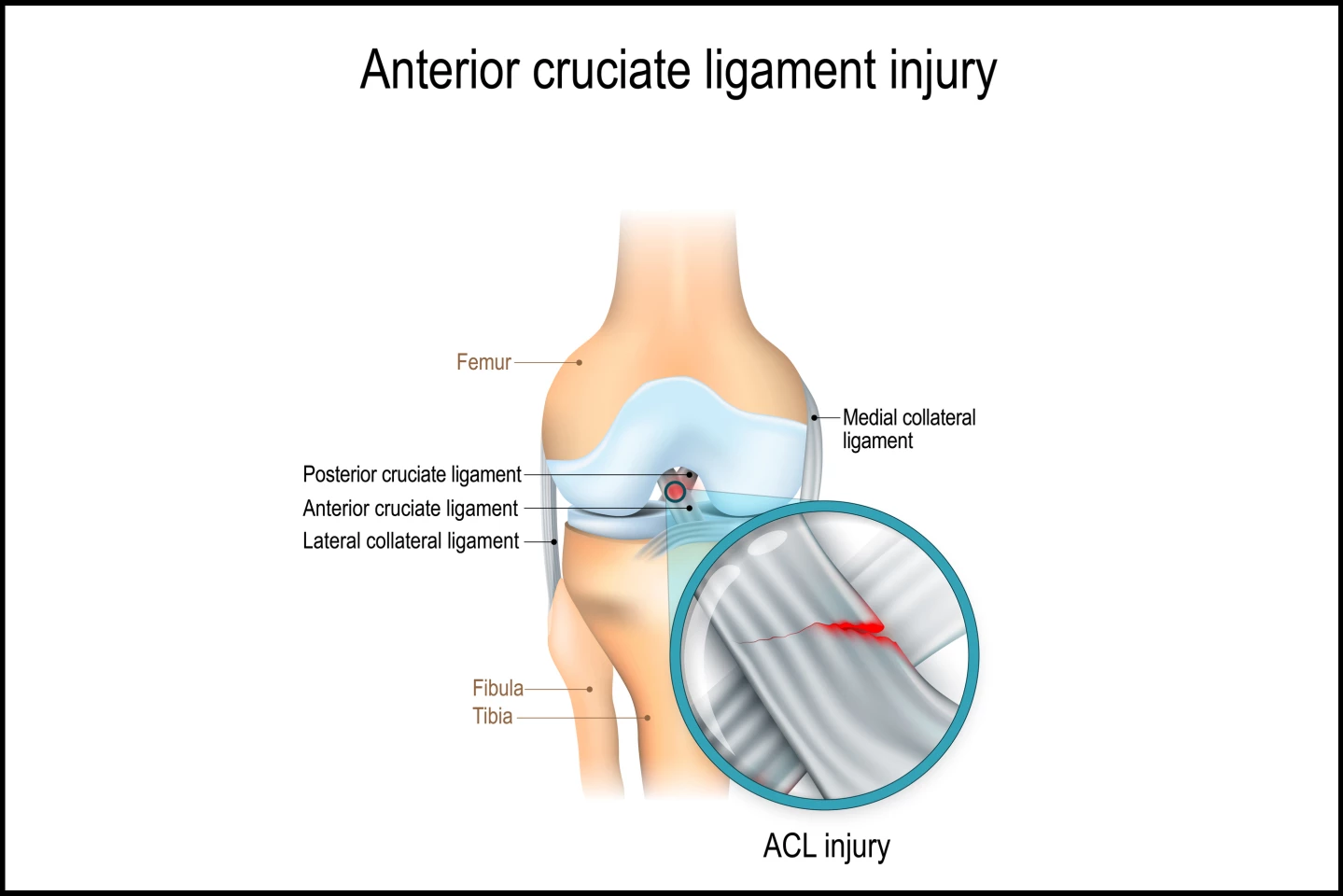

The researchers recruited 112 young adults with a median age of 28 who’d undergone surgical reconstruction of their anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). They were evaluated one year after surgery, then followed up at five years. Participants answered a survey question about grinding or noise in the knee, which is part of the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score, or KOOS. Answers of “often” or “always” were classified as having crepitus. MRI scans were taken to assess cartilage damage, osteophytes (bone spurs), and lesions in the bone marrow. In addition to KOOS, participants also self-reported pain, quality of life, and knee function using validated questionnaires.

Statistical models compared those with and those without crepitus, adjusting for factors like age, sex, and body mass index (BMI). The researchers found that 12 months after surgery, people with crepitus were more than twice as likely to have full-thickness cartilage defects in the patellofemoral joint, behind the kneecap. They also reported worse pain, poor knee-related quality of life, and worse function compared to those who didn’t have crepitus. From one to five years post-surgery, crepitus was found not to predict worsening joint damage; there was no greater risk of progression of OA features seen on MRI scans. Those with crepitus did show greater improvement in pain and function over time, but this was largely because they started worse at year one.

There were some limitations to the study. It was a small sample size; only 112 participants, with about 30% returning for the five-year follow-up. There was a low prevalence of crepitus, with around 21% of participants reporting it, which may limit the strength of the observed associations.

Regardless, it is important to know that crepitus is linked to current joint damage in the form of cartilage loss, but it doesn’t seem to predict future worsening in young people after traumatic knee injury. So, while it may cause worry, crepitus shouldn’t be used as a stand-alone red flag for early OA in this group.

Based on the study’s findings, clinicians can reassure patients that noisy knees following an ACL injury and/or reconstruction surgery are not necessarily a sign of future deterioration. Encouraging continued physical activity and rehabilitation may help counter negative beliefs that crepitus equals “inevitable arthritis.”

The study was published in the journal Arthritis Care & Research.

Source: La Trobe University