A new study has challenged the commonly held belief that consciously suppressing negative thoughts is bad for our mental health, finding that people who did so had lower levels of post-traumatic stress and anxiety, and intrusive thoughts were less vivid. The findings suggest it’s a promising alternative means of treating mental illness.

Like our actions, our thoughts and emotions often need to be controlled, especially when we’re reminded of an unpleasant event. Suppression is a psychological defense mechanism where a person consciously pushes disturbing thoughts and experiences out of their mind as a way of coping with traumatic events.

Conventional thinking in psychological circles, which originated with Freud, is that suppressed content is held by the body and creates a raft of negative downstream effects such as depression, anxiety, stress-related illness and substance abuse. However, a new study by researchers at the University of Cambridge in the UK has found that conventional thinking may be wrong and that suppressing negative thoughts may, in fact, be good for our mental health.

“We’re all familiar with the Freudian idea that if we suppress our feelings or thoughts, then these thoughts remain in our unconscious, influencing our behavior and well-being perniciously,” said Michael Anderson, one of the study’s two authors. “The whole point of psychotherapy is to dredge up these thoughts so one can deal with them and rob them of their power. In more recent years, we’ve been told that suppressing thoughts is intrinsically ineffective and that it actually causes people to think the thought more – it’s the classic idea of ‘Don’t think about the pink elephant.’”

The researchers considered the brain’s mechanism of inhibitory control, the ability to override our reflexive responses, and how it might be applied to memory retrieval, particularly the retrieval of negative thoughts. They recruited 120 people across 16 countries to test whether suppressing negative thoughts was possible and, if so, whether it was beneficial. Participants’ mental health was assessed, and the study included many with serious depression, anxiety, and COVID pandemic-related post-traumatic stress.

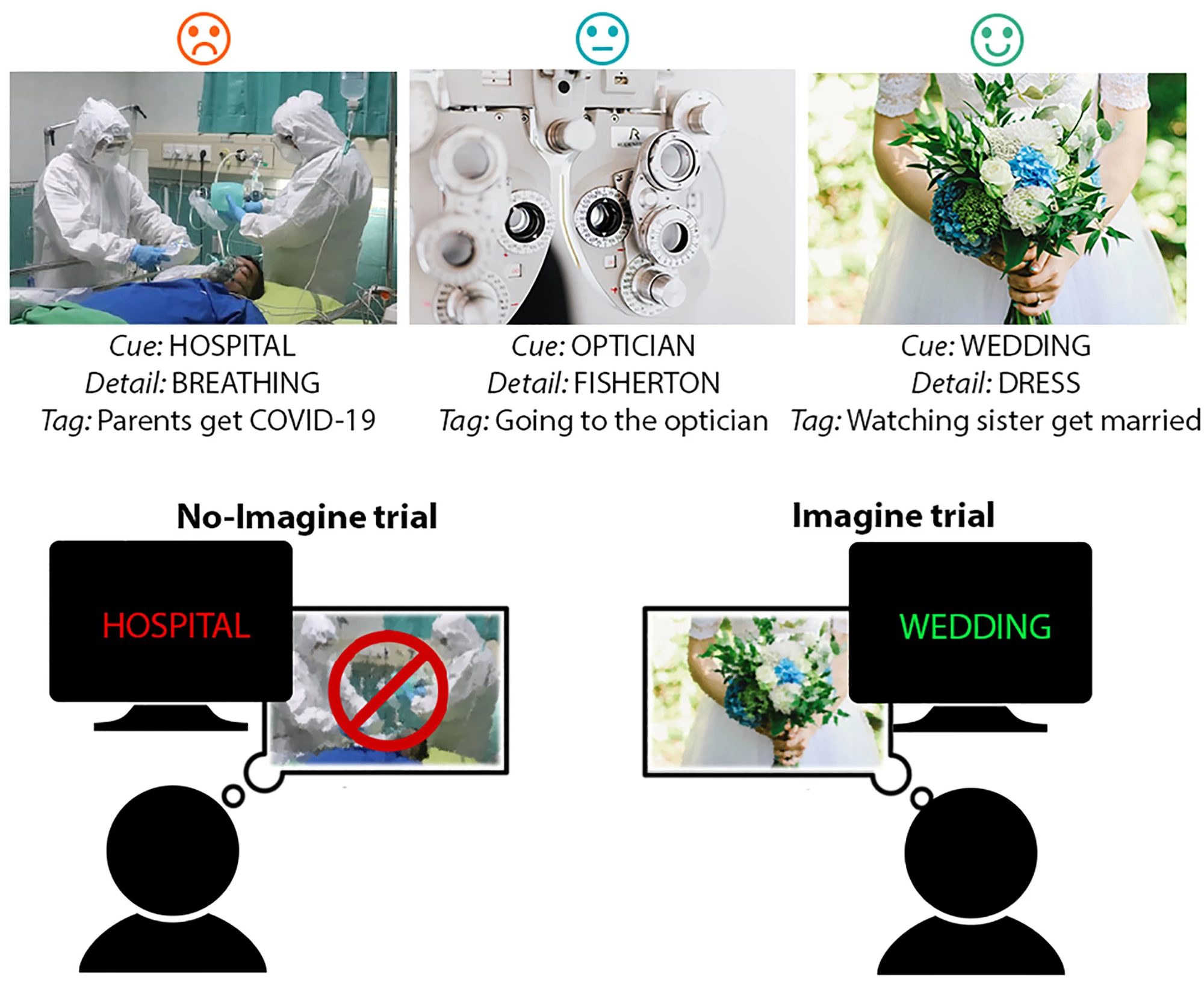

Each participant was asked to think of a number of scenarios that might plausibly occur in their lives in the next two years: 20 negative ‘fears and worries,’ 20 positive 'hopes and dreams,’ and 36 'routine and mundane' neutral events. The fears had to be current concerns that repeatedly intruded into their thoughts.

Participants provided a cue word and a key detail for each scenario. For example, a negative scenario might be "visiting a parent with COVID-19 at the hospital," where the cue word is "hospital" and the key detail is "breathing." A positive might be 'watching my sister get married," where "wedding" is the cue and "dress" is the detail.

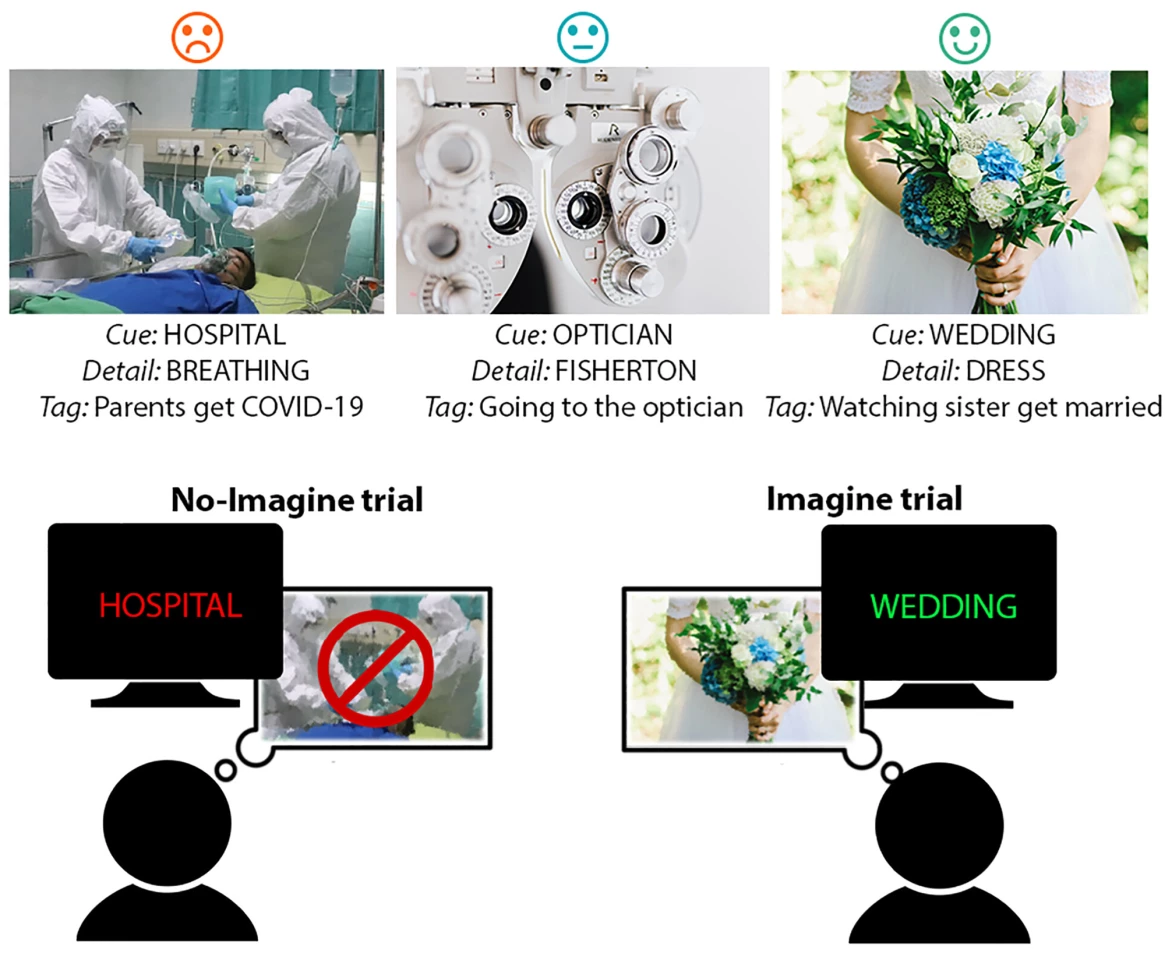

The researchers took each participant through a 20-minute online training session every day for three days, which involved 12 ‘No-Imagine’ and 12 ‘Imagine’ repetitions. For No-Imagine trials, participants were shown one of their negative or neutral scenario cue words and asked to conjure the event in their minds. Then, while staring at the cue, they were asked to stop thinking about the event by blocking images or thoughts the reminder evoked. For Imagine trials, participants were shown a positive or neutral scenario cue word and asked to imagine the event as vividly as possible. For ethical reasons, participants were not asked to vividly imagine a negative scenario.

Prior to the commencement of the study, at the end of the third day and again three months after, participants were asked to rate each event for its vividness, likelihood of occurring, distance in the future, level of anxiety or joy about the event, frequency of thought, degree of current concern, long-term impact, and emotional intensity. They also completed questionnaires to assess changes in depression, anxiety, worry, affect, and well-being.

Immediately after training and three months later, participants reported that suppressed events were less vivid and less fearful. They also reported thinking less about these events.

“It was very clear that those events that participants practiced suppressing were less vivid, less emotionally anxiety-inducing, than the other events and that overall, participants improved in terms of their mental health,” said Zulkayda Mamat, the study’s other author. “But we saw the biggest effect among those participants who were given practice at suppressing fearful, rather than neutral, thoughts.”

Participants with higher anxiety and post-traumatic stress benefitted the most from suppressing their distressing thoughts. Among participants with post-traumatic stress who suppressed negative thoughts, their negative mental health scores fell on average by 16%, compared to a 5% fall for participants who suppressed neutral events.

After three months, participants trained to suppress their fears continued to show reduced depression and a trend towards reduced negative affect. Those trained to suppress neutral events showed neither of these effects.

Importantly, suppressing negative thoughts did not lead to a ‘rebound,’ where events are recalled more vividly. Only one participant out of 120 showed higher detail recall for suppressed items after training, and six of 61 participants that suppressed fears reported increased vividness for No-Imagine events.

“What we found runs counter to the accepted narrative,” Anderson said. “Although more work will be needed to confirm the findings, it seems like it is possible and could even be potentially beneficial to actively suppress our fearful thoughts.”

The study was published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: University of Cambridge