Let's face it, dietary fiber is not the most scintillating topic, even though for the last 50 years it's been well accepted that it's valuable for good gut health. But we're now coming to understand that fiber itself is an umbrella term, and one particular type – which is abundant in a common breakfast food – may trigger the same beneficial metabolic functions that GLP-1 agonists like Ozempic do, without the price tag or side-effects.

"We know that fiber is important and beneficial; the problem is that there are so many different types of fiber," said Frank Duca, an associate professor at the University of Arizona. "We wanted to know what kind of fiber would be most beneficial for weight loss and improvements in glucose homeostasis so that we can inform the community, the consumer and then also inform the agricultural industry."

In a study led by Duca, researchers undertook a thorough analysis of how different types of fiber impacted the gut microbiota, which play such an important role in how food is processed in our digestive system. They looked at pectin, beta-glucan, wheat dextrin, starch and cellulose, all plant-based fibers, and found that one in particular punched above its weight when it came to naturally fighting obesity.

Many previous studies, such as one that compared a high-fiber diet with one rich in fermented foods, only looked at 'fiber' as a single unit of nutrition. While as a whole, both soluble and insoluble forms of dietary fiber have wide-ranging health benefits – from satiety to lowering blood cholesterol levels – the sum of the parts has not offered insight to its weight-loss potential.

Here, the researchers quickly homed in on one type of fiber, beta-glucan, which has previously been singled out as playing a role in moderating the appetite and satiety hormones peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). Last year, a study out of the University of Agriculture, Faisalabad in Pakistan demonstrated that oats in particular, high in beta-glucan, impacted those hormones in ways beneficial for weight management.

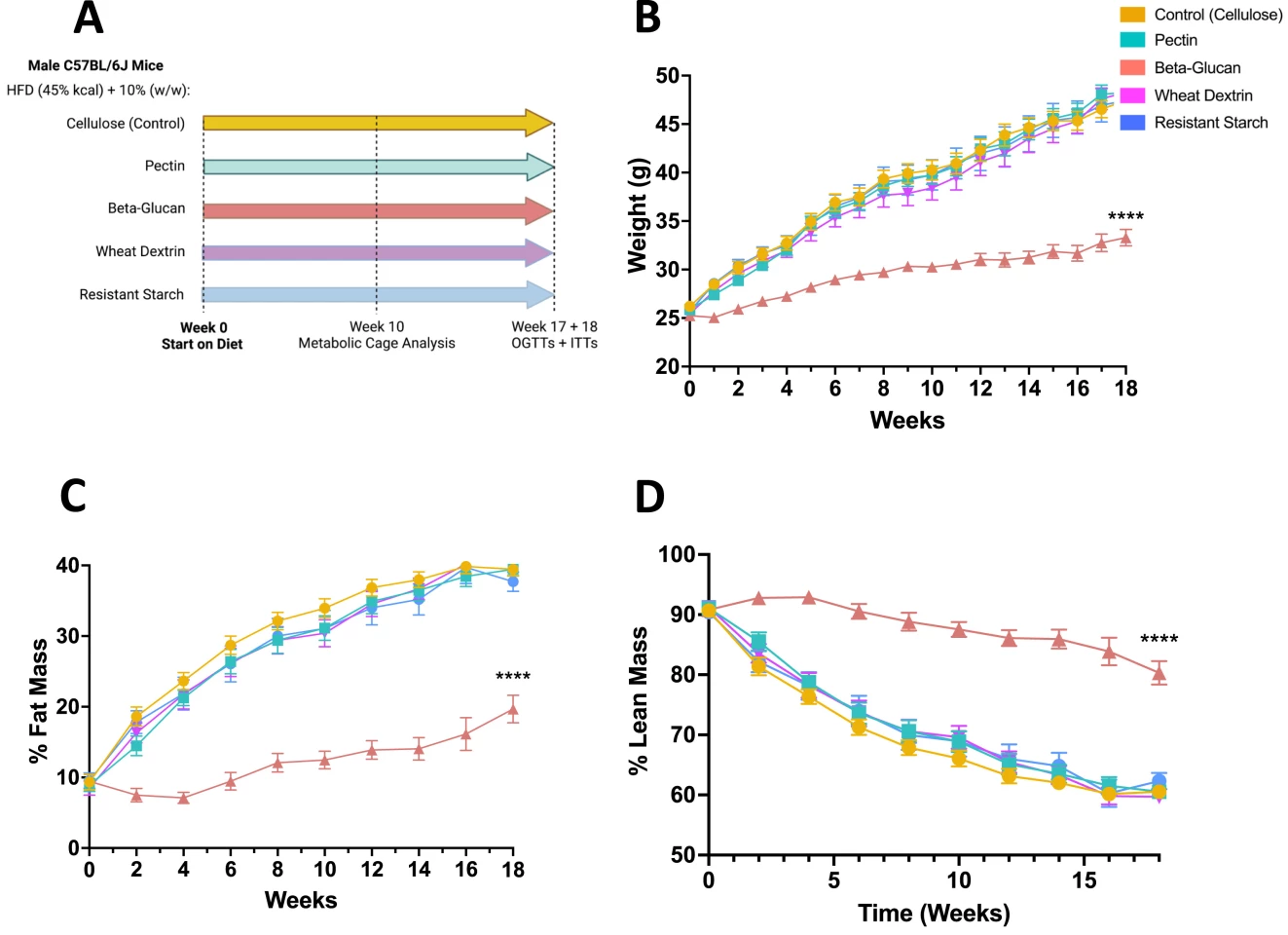

In this latest study, the researchers allocated mice into five groups to all be fed high-fat, high-sucrose diets (HFD). Each group's diet also consisted of either 10% cellulose (control), pectin, beta-glucan, wheat dextrin or resistant starch. Health markers were measured over 18 weeks, assessing percentages of weight gain, fat mass and lean mass. They also looked at the effect of the diets on blood glucose levels after eating, up to two hours after consumption.

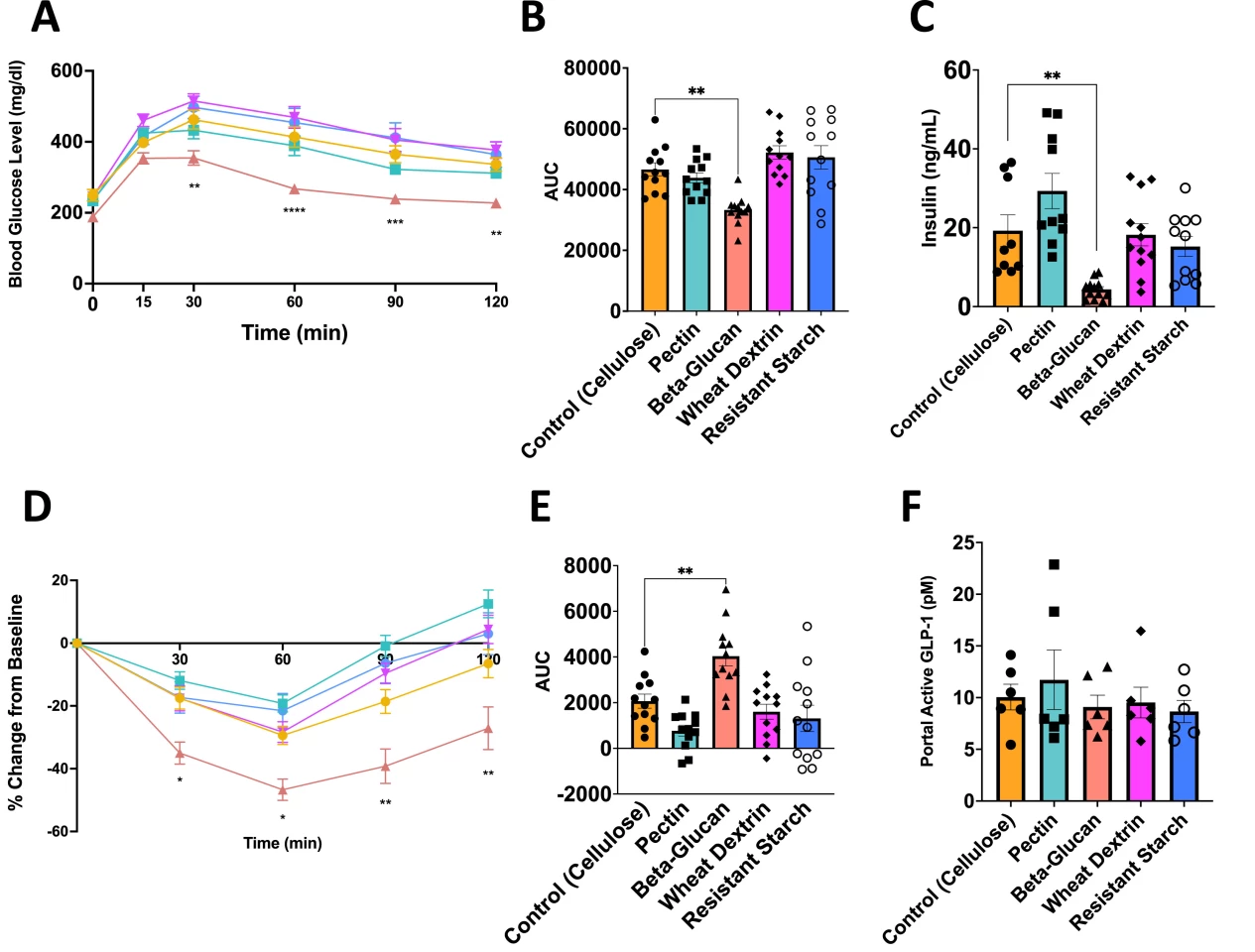

What they found was that the animals on the 10% beta-glucan diets had significantly less weight gain despite their high-fat, high-sugar diet, as well as significantly less fat mass yet significantly higher retention of lean mass. These mice also demonstrated sustained energy expenditure, measured by their movements over 24-hour periods.

The beta-glucan cohort were also the only group to show improved insulin sensitivity and beneficial blood-sugar levels throughout the 18 weeks.

Further analysis indicated that the animals on the beta-glucan-supplemented diets had developed the kind of microbiota that set them up for all of these positive health outcomes, altering the gut's bacteria and the molecules produced through digestion. These molecules, known as metabolites, are thought to be the key piece of the puzzle when it comes to how fiber encourages weight loss.

They found that one metabolite, butyrate, was the driver of this effect. Butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) is produced by certain gut bacteria in the fiber fermentation process, stimulates the release of GLP-1, which we've come to understand plays such an important role in communicating to the brain that feeling of 'fullness' when we eat. Semaglutide drugs like Ozempic synthetically create this gut-brain scenario, though in a more potent way that doesn't face the same kind of rapid deterioration as when it occurs naturally.

"Part of the benefits of consuming dietary fiber is through the release of GLP-1 and other gut peptides that regulate appetite and body weight," Duca said. "However, we don't think that's all of the effect. We think that there are other beneficial things that butyrate could be doing that are not gut-peptide-related, such as improving gut barrier health and targeting peripheral organs like the liver."

Butyrate has previously been shown to induce the burning of brown fat in mice, which suggests that beta-glucan was helping fuel that specific lipid high-calorie fat availability, reducing the 'white fat' accumulation that is a hallmark of weight gain and obesity.

"Only β-glucan (beta-glucan) supplementation during HFD-feeding decreased adiposity and body weight gain and improved glucose tolerance compared with HFD-cellulose, whereas all other fibers had no effect," the researchers noted. "This was associated with increased energy expenditure and locomotor activity in mice compared with HFD-cellulose. All fibers supplemented into an HFD uniquely shifted the intestinal microbiota and cecal short-chain fatty acids; however, only β-glucan supplementation increased cecal butyrate concentrations. Lastly, all fibers altered the small-intestinal microbiota and portal bile acid composition."

Oats, as well as barley, have the highest concentrations of beta-glucan, but it's also found in rice, mushrooms and seaweed. Oats contain around 3-5% of this fiber per cup of dry cereal, and cooking (not baking) does not diminish its concentration. Duca now hopes to work on developing 'enhanced fibers' that can boost the release of butyrate during digestion.

The study was published in The Journal of Nutrition.

Source: University of Arizona