Working-age US adults are dying at far higher rates than their peers from high-income countries, even surpassing death rates in Central and Eastern European countries, and midlife mortality rates in the UK are not great either. A new study has examined what's caused this rise in the death rates of these two cultural superpowers.

Life expectancy started to rise around 1840 at a pace of almost 2.5 years per decade and has continued to the present day. A 2021 study calculated that if the current pace continues, most children born this millennium will live to celebrate their 100th birthday. However, new research by the Leverhulme Center for Demographic Science (LCDS) at the University of Oxford and Princeton University has revealed some troubling trends for those in midlife, particularly in the US and the UK.

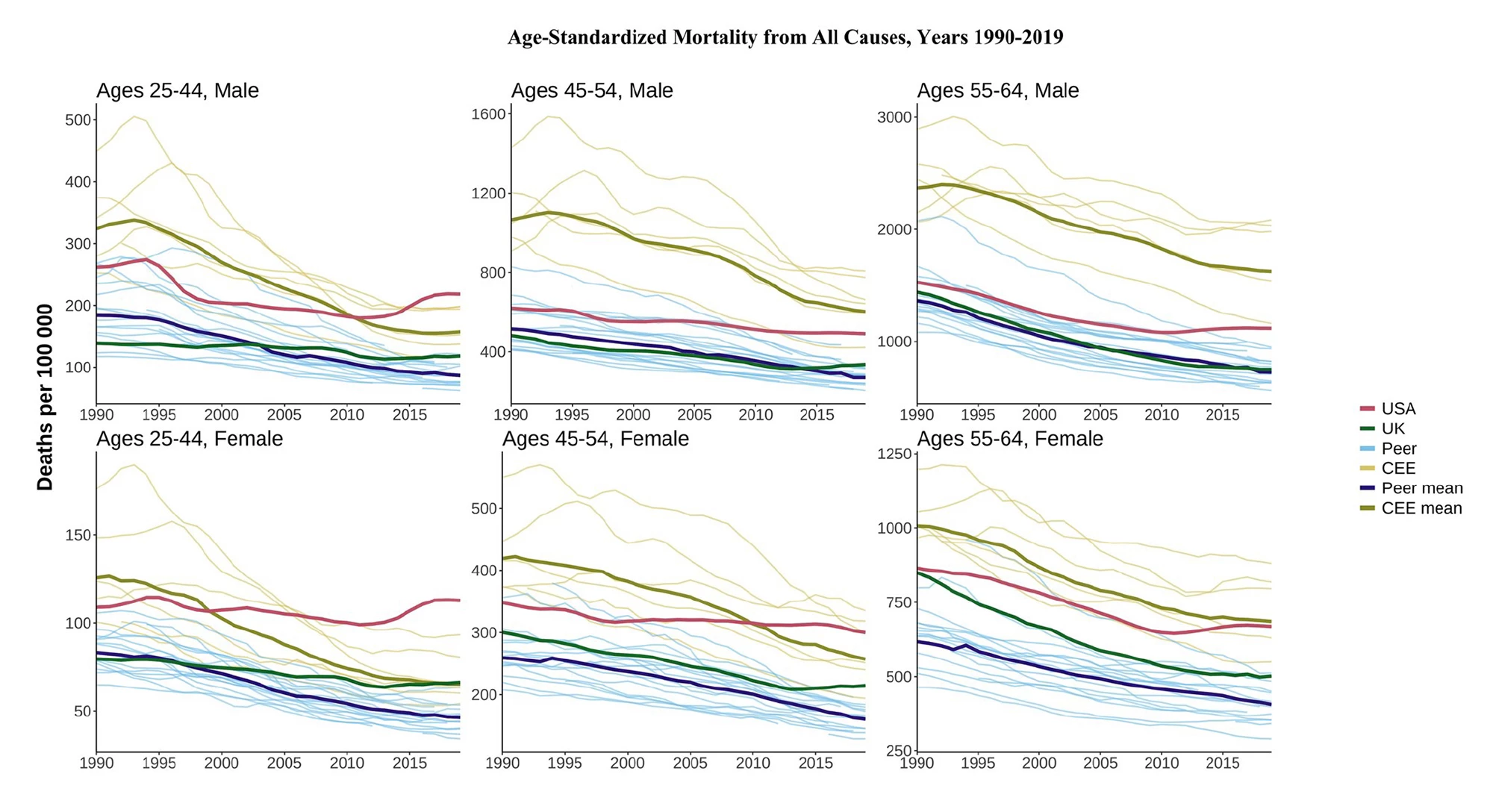

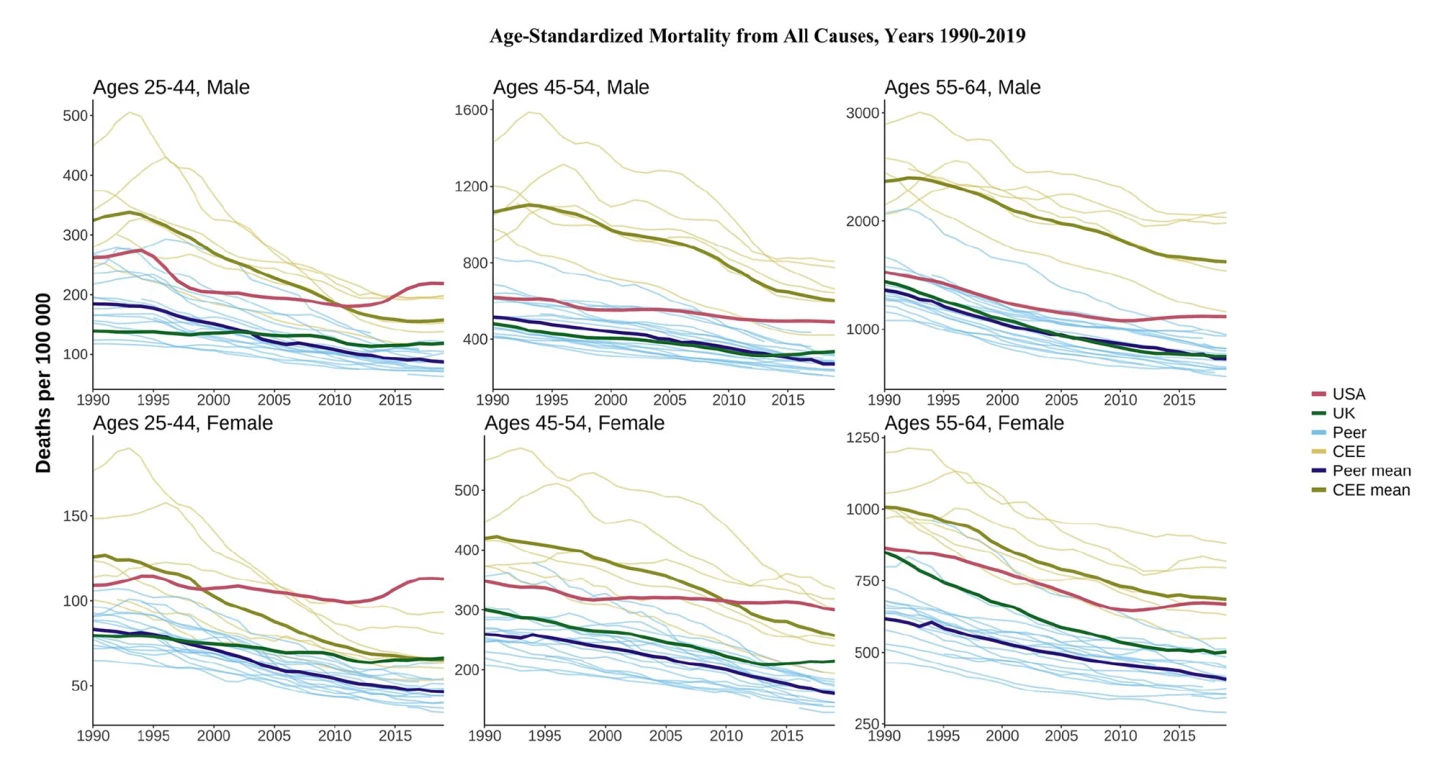

“Over the past three decades, midlife mortality in the US has worsened significantly compared to other high-income countries, and for the younger 20- to 44-year-old age group, in 2019, it even surpassed midlife mortality rates for Central and Eastern European countries,” said Katarzyna Doniec, the study’s corresponding author. “This is surprising, given that not so long ago, some of these countries experienced high levels of working-age mortality, resulting from the post-socialist [economic] crisis of the 1990s.”

The figures at a glance

- In 2019, all-cause mortality for US males and females was 2.5 times higher than in other high-income peer countries

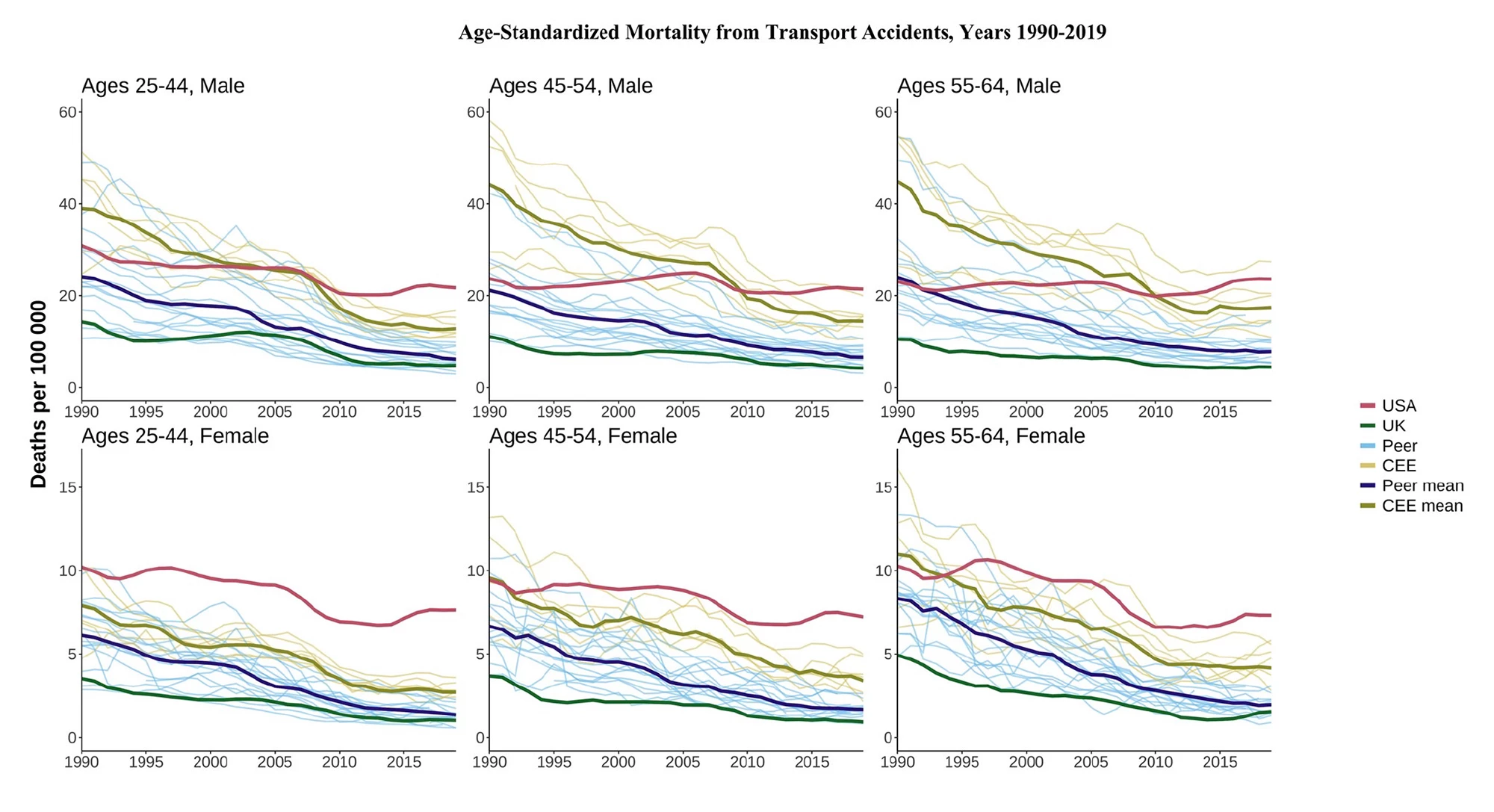

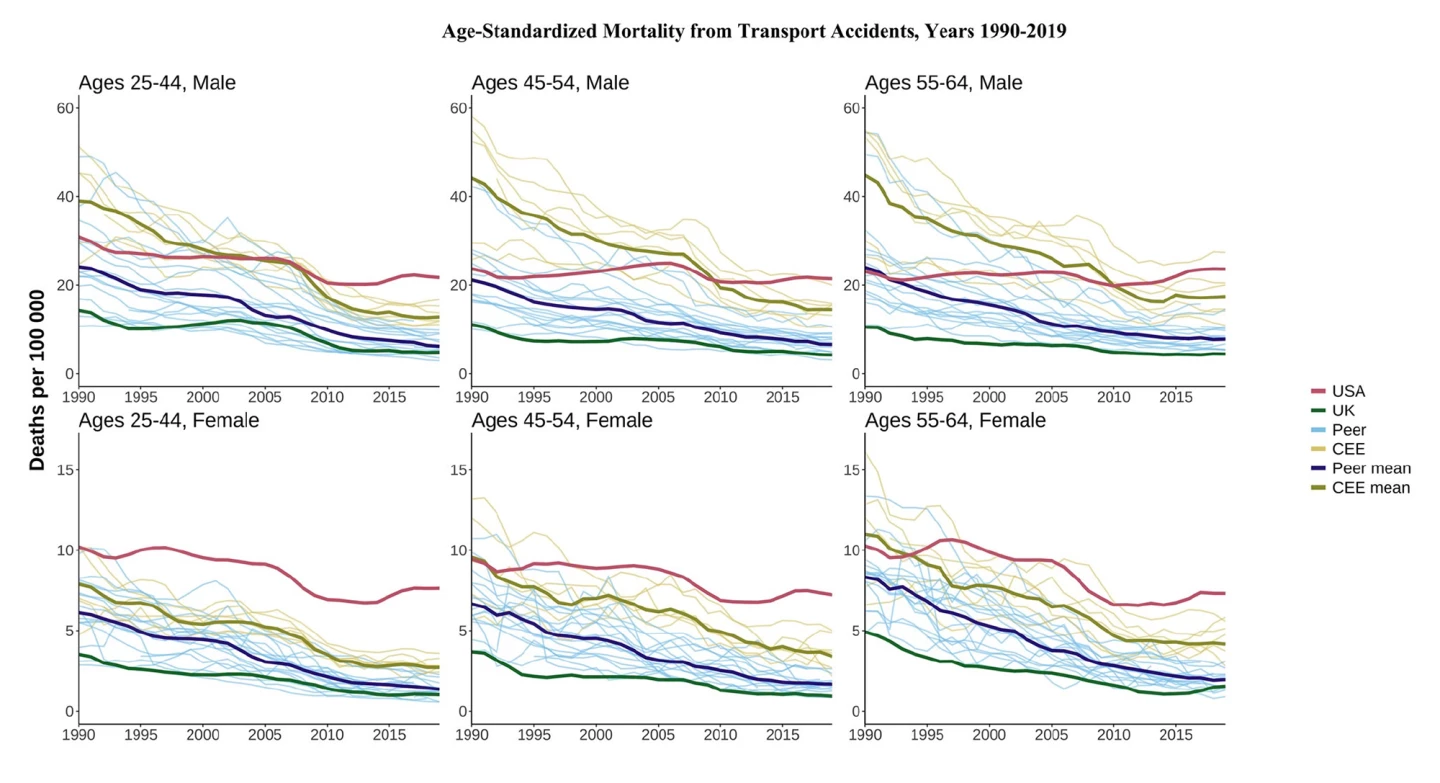

- US homicide rates were almost 15 times higher than other countries in 2019, while, in the same year, transport-related deaths were 3.5 times higher

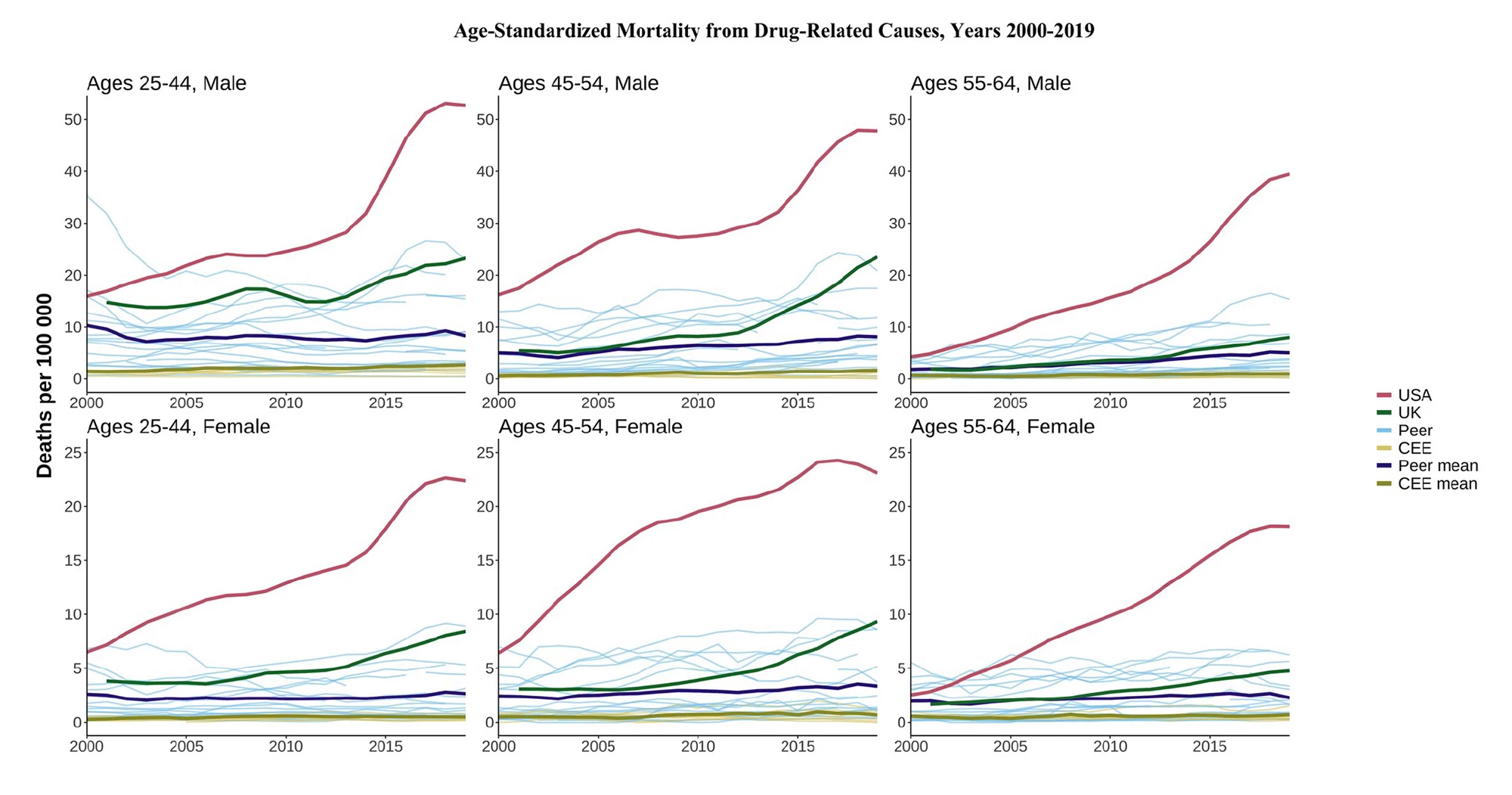

- Between 2000 and 2019, US drug-related deaths were up to tenfold higher than some countries

- US females aged 25 to 44 were the only group whose mortality was higher in 2019 compared to 1990, increasing by 3.7%

- UK mortality has diverged from peer countries, especially for younger middle-aged groups and females

Mortality data are important because they suggest persistent risk patterns in particular communities and show trends in specific causes of death over time. But all-age mortality isn’t particularly useful for health planning or monitoring. Age-specific mortality rates allow for comparisons between countries and over time for specific age groups.

Using data from the World Health Organization (WHO) Mortality Database, researchers analyzed trends in midlife mortality from 1990 to 2019 in the US, the UK, and 16 other high-income countries (Austria, Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Switzerland) and seven Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries (Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia). All-cause and cause-specific mortality rates, as deaths per 100,000 individuals, were calculated for three age groups – 25 to 44, 45 to 54, and 55 to 64 – by country, sex, and year.All-cause mortality

US trends diverged significantly from those of other countries regarding all-cause mortality, most noticeably for 25- to 44-year-olds. In 2019, the US all-cause mortality rates were 2.5 times higher for males and females compared to ‘peer’ countries, high-income countries that are comparable to the US.

The UK’s numbers were better than in the US, but its performance flagged over time compared with its high-income peers, particularly at the youngest ages. UK females in younger midlife fared worse than peer and CEE countries across the years of analysis. Death rates among two age groups, 25 to 44 and 45 to 54, of both sexes were generally stable and did not show improvement since the early 2010s, consistent with stalled life expectancy.

“Our study adds to the evidence that UK mortality is increasingly diverging from its high-income peers, especially for younger women,” said Jennifer Dowd, lead author of the study. “The causes of this worsening health will be important to understand going forward.”

Transport accident deaths

Compared with high-income peers and CEE countries, the US has higher mortality rates for many causes. For example, while deaths from transport accidents have fallen for most countries since 1990, the rates for US males aged 25 to 44 flatlined in the late 1990s and early 2000s and have increased since 2010. By 2019, they were around 3.5 times higher than peer countries and 1.7 times higher than CEE countries.

Homicide

US homicide rates far exceeded those of other countries for all age and sex groups. For males aged 25 to 44, the homicide mortality rate was nearly 15 times higher than both the peer and CEE means in 2019.

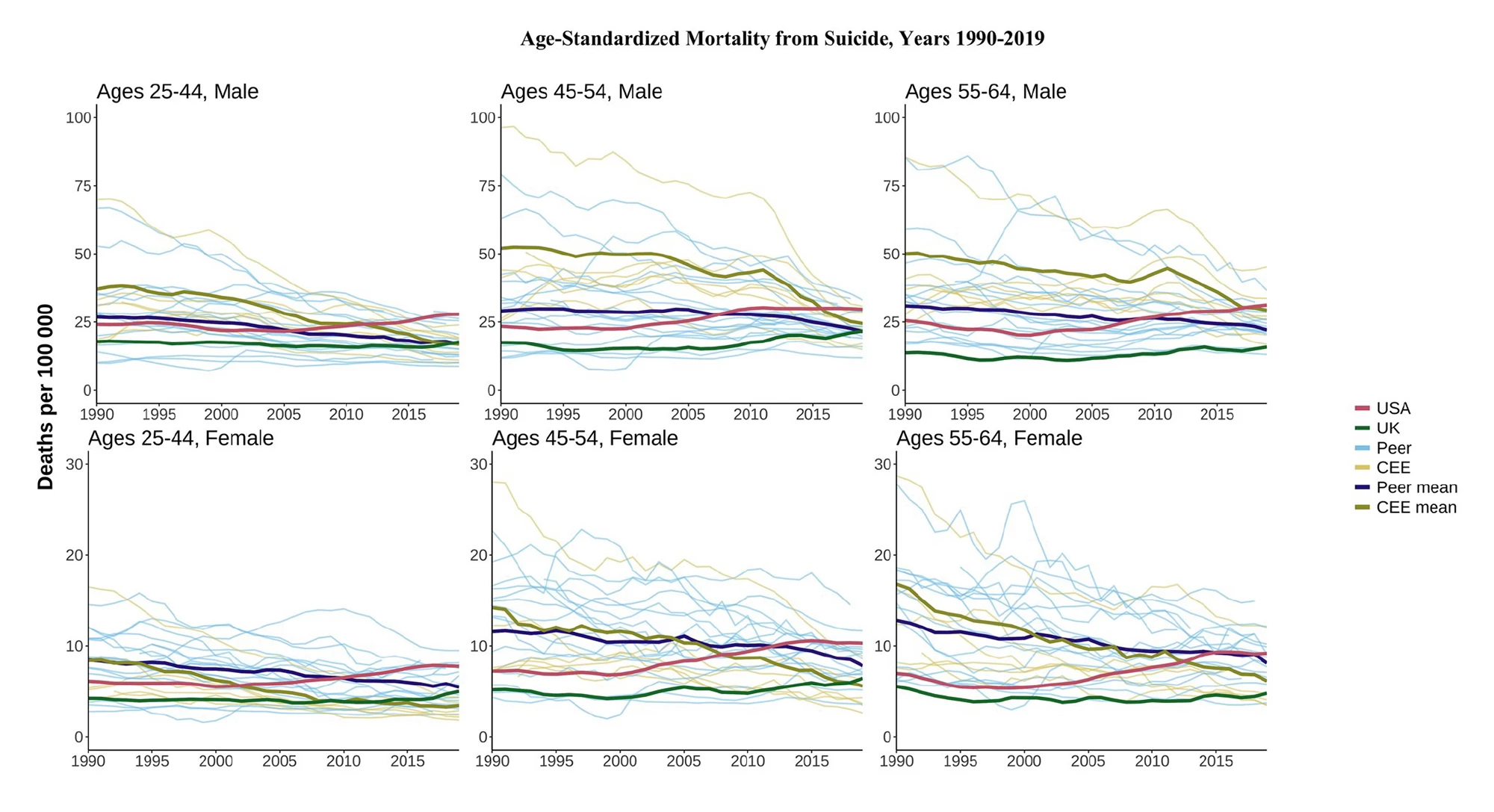

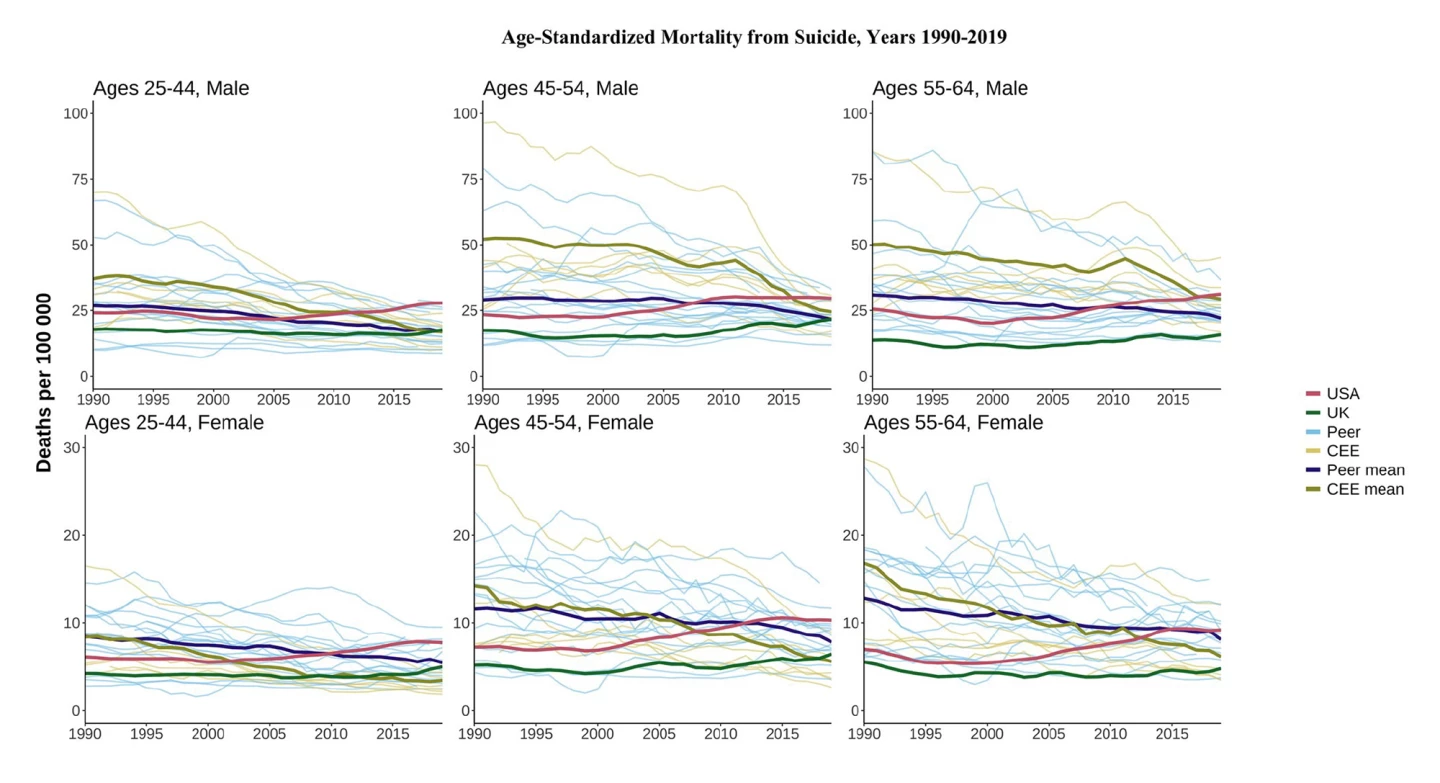

Suicide

Suicide mortality rates in the US were mostly below the high-income country mean in the 1990s, rising gradually from the late ’90s/early ’00s to land above peer and CEE means by 2019.

UK suicide mortality rates were generally low compared to those of other countries. While increases at younger ages in the 2010s brought the country closer to high-income peers and CEE means, it was still far below that in the US.

Alcohol-related deaths

In 1990, the US was below the peer mean for alcohol-related deaths in most age and sex groups but has trended upward since the late 2000s, ending the analysis period above both the UK and the peer mean in most age and sex categories.

While the UK’s alcohol-related mortality rate was higher than the peer mean in most age and sex categories, it has mostly flatlined since the 2000s.

Drug-related deaths

Again, the US diverged significantly from other countries when it came to drug-related deaths. The highest mortality rates were seen in 45- to 54-year-old males, but the increases were universal across all age and sex groups. Between 2000 and 2019, mortality increased threefold in some age and sex groups and up to tenfold in others, a remarkable divergence from other countries.

Drug deaths also increased in the UK during the late 2000s/early 2010s and were worse compared to peer means, but absolute levels remained below that of the US. The unique nature of the US’ high drug-related mortality was confirmed when it was compared to trends in high-income peer and CEE countries, which remained relatively flat in most age and sex groups.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the general term for conditions affecting the heart or blood vessels, the most common being heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and heart rhythm disorders (arrhythmias).

CVD mortality in individuals aged 55 to 64 in the US was similar to or better than that in the UK in 1990, but both countries saw a gradual decline followed by stagnation for both sexes by 2019. By 2019, CVD mortality in the US in this age group was worse than in all peer countries and some individual CEE countries.

The stagnation in US CVD mortality improvements was more evident at younger ages, particularly for females. By 2019, CVD mortality for females aged 25 to 44 and 45 to 54 was higher than the CEE mean despite much higher CEE levels in 1990. And, UK CVD mortality at the same ages was above the peer mean by 2019.

Lung cancer

For males, lung cancer mortality rates declined in most countries across all ages, with CEE levels still higher in 2019 than in all high-income peers. For females, the patterns were more varied.

For those aged 55 to 64, lung cancer mortality rose in the CEE and high-income peer countries over this period compared to men, reflecting different smoking initiation and cessation patterns. US females aged 55 to 64 showed a substantial decline from 1990 levels, which were much higher than in peer countries. In contrast, UK females of the same age had rates above those of peers for most of this period.What do the study’s findings mean?

The study demonstrates that most countries have experienced declines in all-cause mortality over the three decades to 2019. The notable exception is the United States, whose divergence from comparable high-income countries in age-standardized mortality rates of 25- to 64-year-olds has accelerated over time. Strikingly, for US females aged 25 to 44, all-cause mortality rates were higher in 2019 than in 1990. The country’s higher mortality was especially noticeable when it came to preventable deaths: homicides, deaths from transport accidents, and so-called ‘deaths of despair’ related to suicide and alcohol and drug use.

The UK, too, is lagging behind its high-income peers. Death rates are increasing for people aged 45 to 54, and for 25- to 54-year-olds, rates have flatlined instead of improving. While it performed pretty well insofar as preventable deaths are concerned, these ‘good’ results were countered by stalling improvements in CVD and cancer and increasing drug deaths.

“Although levels of midlife mortality in the UK are substantially lower than those in the USA, there are signs of trouble on the horizon relative to the rest of Europe,” said the researchers.

The study didn’t cover the years when the world was gripped by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which time the US experienced worsening life expectancy, further widening the gap between it and other high-income countries. The researchers suggest that future studies examine the effects of the pandemic on long-term, cause-specific mortality trends when reliable data becomes available. Overall, given the more favorable mortality levels in high-income peer countries, the study’s findings imply significant room for mortality improvement in both the US and the UK.

The study was published in the International Journal of Epidemiology.

Source: LCDS