One of the problems that can arise when providing housing for asylum seekers is that communities can see a burden involved, but not necessarily a benefit. The SolarCabin refugee shelter is designed to tackle this, with a large, visible solar array used to produce a surplus of electricity that can help power the local area.

The concept was developed in response to the "A Home away from Home" competition in the Netherlands, which asked participants to design temporary housing for asylum seekers in a climate where demand is constantly fluctuating. The contest was run by the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) and received 366 entries in total, of which the SolarCabin was one of six winners.

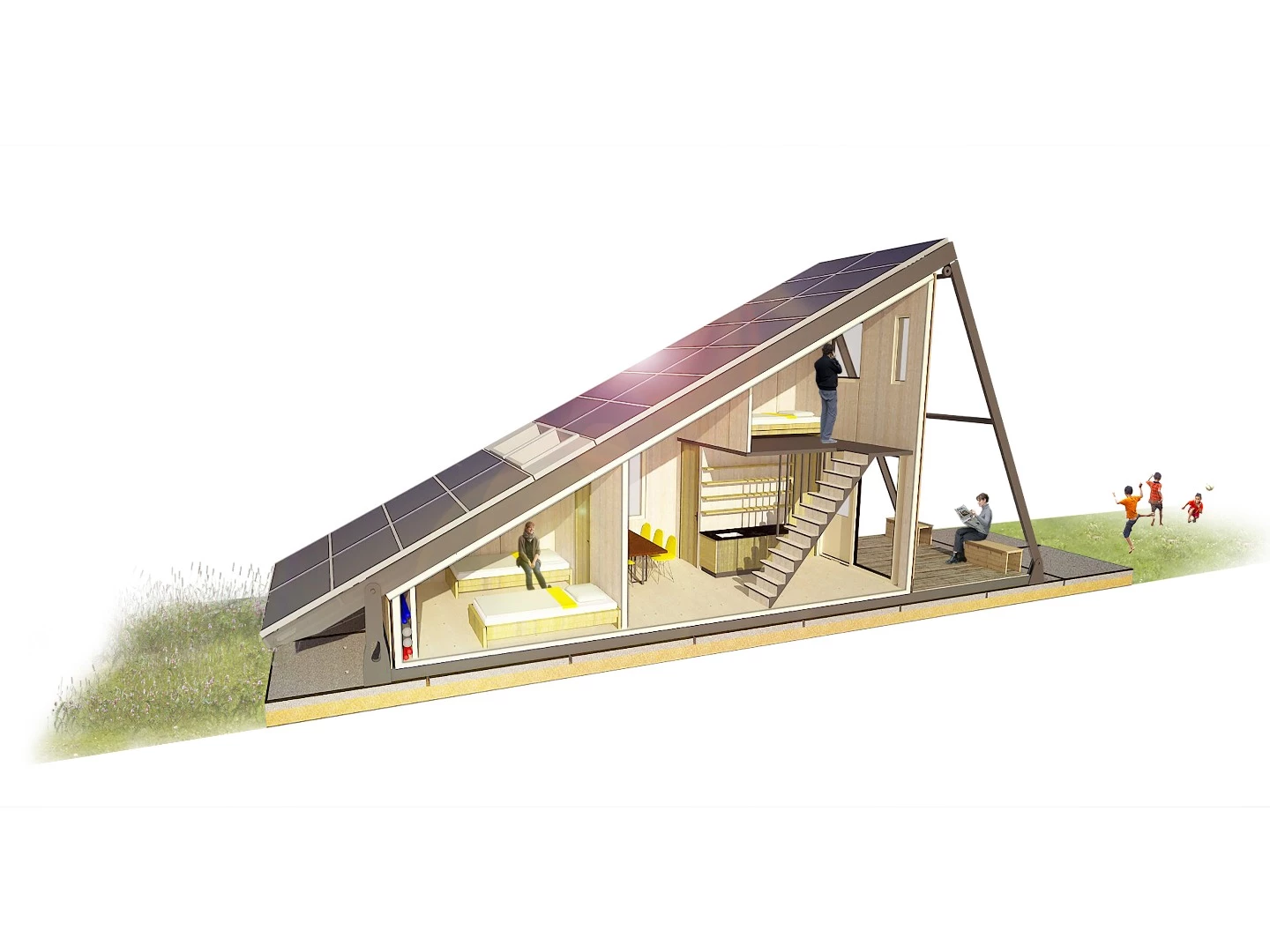

Designed by Bram Zondag of Bureau Zondag and Arjan de Nooijer of dNArchitectuur, it combines a number of ideas. It has a modular, steel/timber frame construction that makes it quick to construct and cost effective, as well as being adaptable for use by other groups, such as students, first-time buyers or holidaymakers. Once a kit is on site, the aim is for a SolarCabin to be constructed in a day, with the use of a crane.

Zondag and de Nooijer say the shelter can be made either in a form that's suitable and financially viable for use over short-term periods of up to five years, or for use more permanently over 10 years or more.

Most importantly, though, the SolarCabin was conceived to provide conspicuous added value to a community. Not only is it designed to feed its surplus of electricity generated back into the local community, but also to make clear that it is doing so.

In this way, the look of the structure is very clever. It is shaped like a lean-to, with one large sloping face covered in solar panels. This unusual design will draw people's attention, making them aware of the solar array. As a result, communities will see that an investment in a SolarCabin is also an investment in renewable energy.

In the Dutch climate, the SolarCabin can produce approximately 4,800 kWh a year. It's not clear how much electricity is required to run one of the units, but its thought it would be less than half or one third of that produced. Given that the design is currently only a concept, any figures will only be projections. By virtue of being one of the competition winners, however, a prototype of the SolarCabin will be created, with funding from the COA, in the hope that it will increase the likelihood of it and the other winners going into full production.

"I strongly believe in the persuasive force of prototypes you can actually touch and experience the spatiality of," explains housing manager of COA Carolien Schippers on the organization's website. "By contributing to the manufacturing of these prototypes we, as COA, want to help speed up the process towards the practical implementation of the designs."

Zondag and de Nooijer say it would be possible to construct the SolarCabin in many different configurations and that it would be available with various options. A full kit for building one of the units could be easily delivered to a site and set up quickly, while circular design principles mean that the constituent parts could also be used independently of each other once a unit was disassembled.

The A Home away from Home competition was launched on January 18, with the six winning designs announced on June 29. The winning teams are to develop their full-size prototypes over the coming months.

Sources: SolarCabin, A Home away from Home