In the winter months, at the bottom of Lake Akan in Hokkaido, Japan, harmless underwater algae balls that can grow to be bigger than basketballs are protected from death by an ice shield on top of the water. That shield is expected to thin thanks to global warming, causing the balls to join the list of species threatened by climate change, according to researchers at the University of Tokyo.

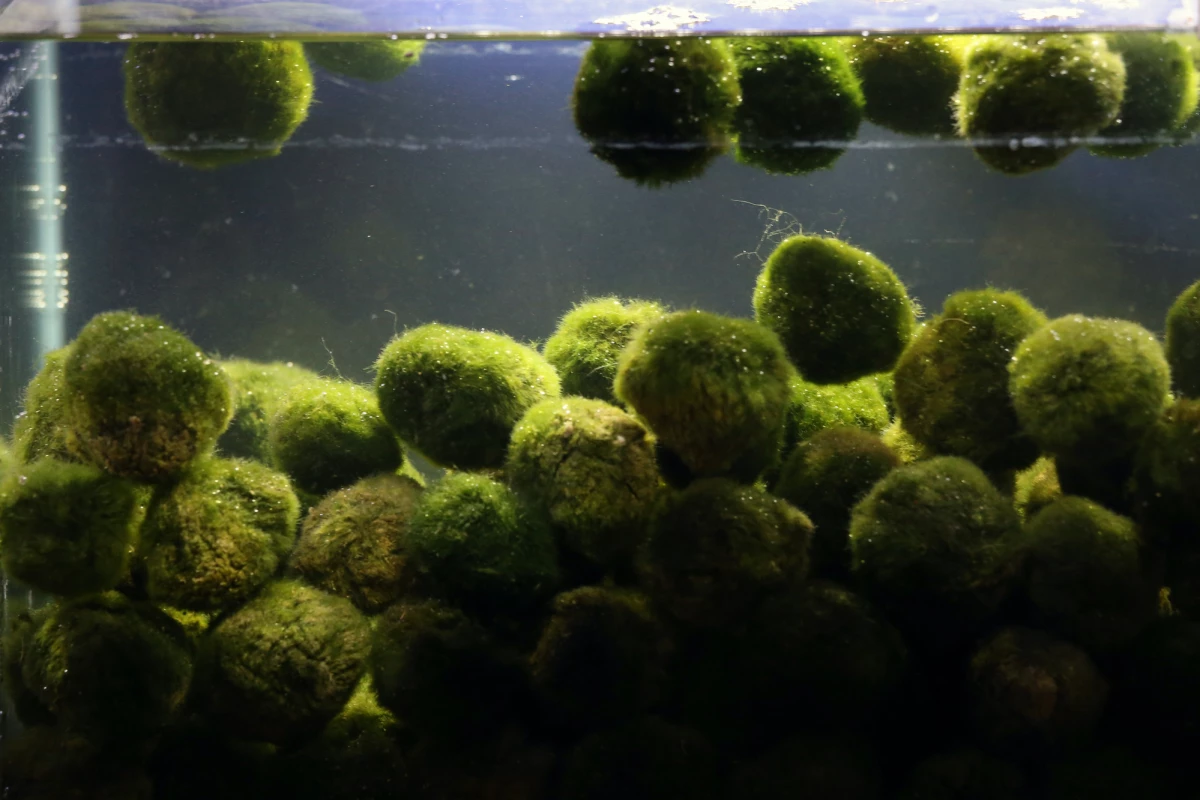

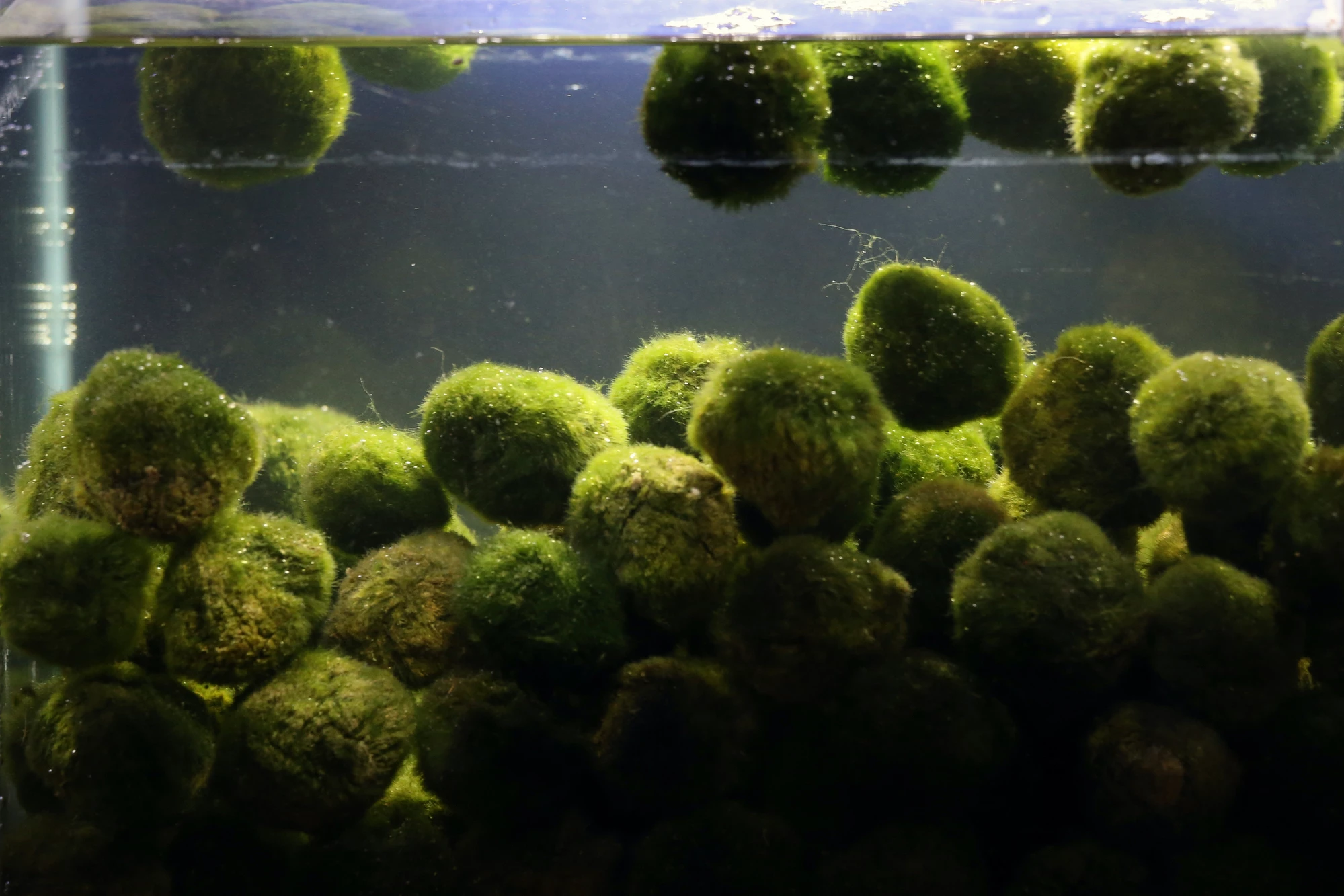

Known as marimo algae balls, the lifeform is something of a hero in Japan, where they are popularly known (incorrectly) as marimo moss balls. The soft, bright green balls have their own (somewhat off-color) mascot, are often grown as a sort of pet in fish tanks, and have their own festival. There's even an observation center in the middle of Hokkaido's lake Akan that draws over a half-million visitors each year.

Scientifically known as Aegagropila linnaei, the balls form from the rolling motion of the lake. They start out as small as a pea, grow about five millimeters per year, get up to a foot wide, and can live for centuries. Much like trees, they develop growth rings as they age. The number of marimo balls living in lakes around the world has been rapidly diminishing, with pollution and human intervention cited as major causes. Now, the larger specimens of marimo balls remain in Lake Akan alone.

Because of the global die-off of the species and the desire to preserve the remaining specimens in Lake Akan, a team of researchers at the University of Tokyo undertook a study to see how the access to sunlight in the winter months might be affecting the organisms.

“We know that marimo can survive bright sunlight in warm summer waters, but the photosynthetic properties in marimo at low winter temperatures have not been studied, so we were fascinated by this point,” said Project Asst. Prof. Masaru Kono from the Graduate School of Science at the University of Tokyo. “We wanted to find out whether Marimo could tolerate it and how they respond to a low-temperature, high light-intensity environment.”

So the team headed out to Lake Akan and measured the intensity of sunlight underwater, both when the lake was ice-free and when it was covered in ice. They then harvested a few small marimo balls measuring about 10 to 15 cm (3.9 to 5.9 inches) in diameter and took them back to the lab. There they exposed strands of algae from the balls to ice and artificial light that recreated the conditions they observed at the lake.

In cold water, A. linnaei enters a state of hibernation, with only a thin coating of algal filaments on its surface, which is quite different from its more robust and furry "summer coat." Therefore, it can't handle as much sun in the winter as it can in the summer. In fact, the researchers found that the balls could only take up to six hours of sunlight a day in cold water before cells associated with photosynthesis died off, leading to the death of the entire organism. It was also discovered that even if the balls were degraded after four hours of strong light exposure, 30 minutes of moderate light helped them regenerate. Interestingly, it took the moderate light to help them restore themselves; darkness did not have the same effect.

Because Lake Akan gets more than 10 hours of sunlight per day in the winter months, the ice and snow that completely covers the lake has shielded the marimo balls from getting blasted by too many rays. This covering typically reaches a thickness of about 20 inches (508 mm). However, as that ice thins due to warming temperatures and more sunlight makes its way through the winter water, the researchers fear that the balls will come under a greater threat of extinction.

To investigate further, the researchers will be studying the effect of excess light on complete balls of marimo rather than just strands, to see if the round structure of the organism might offer it some additional protection from the damaging rays.

"In the present study, we used dissected filamentous cells, so we did not consider the effects of the structure of the spherical marimo and how it might protect against exposure to bright light," said Kono. "However, if damage to the surface cells increases under longer exposure to the direct sunlight, in an extreme case, this may affect the maintenance of their round bodies and lead to the disappearance of giant marimo. So, we need to constantly monitor the conditions at Lake Akan in the future."

The research has been published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences.

Source: University of Tokyo