If you want to gather oceanographic data over long distances, the use of an "underwater glider" is often the best way to go. A novel system from California-based company Seatrec should soon power such vehicles, utilizing the temperature gradient of ocean water.

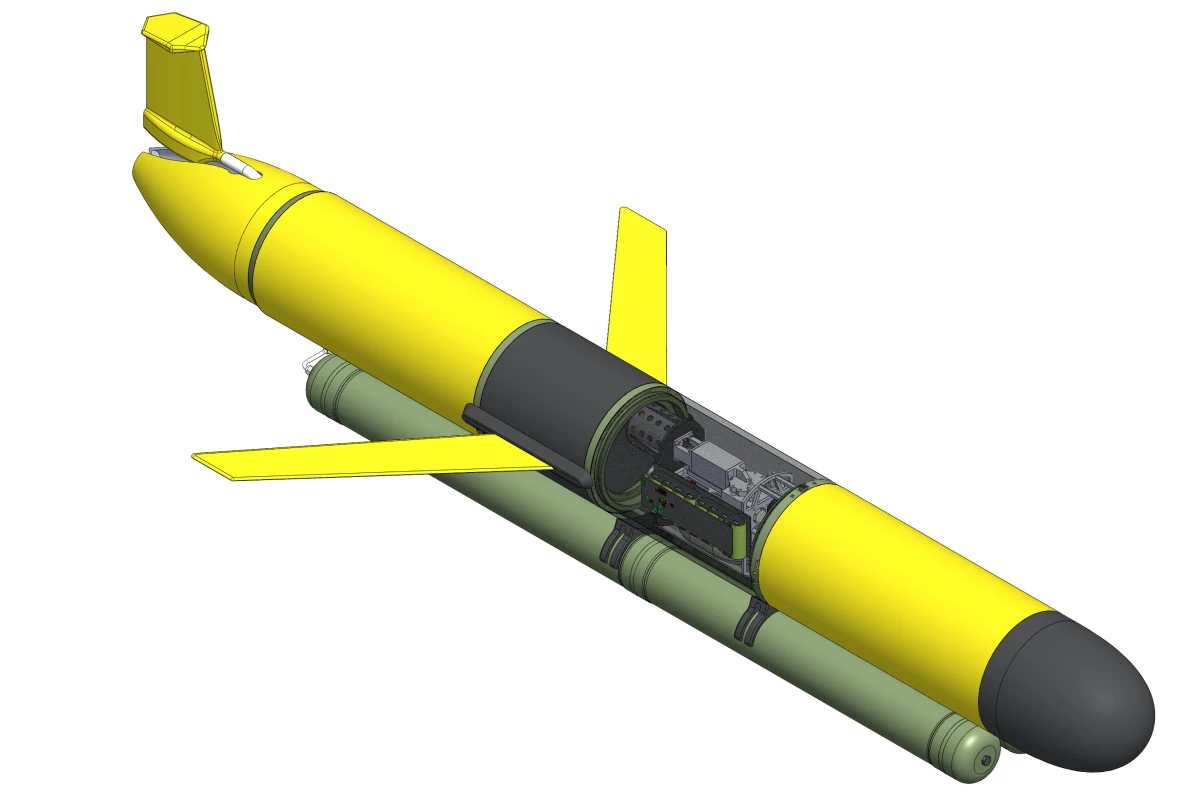

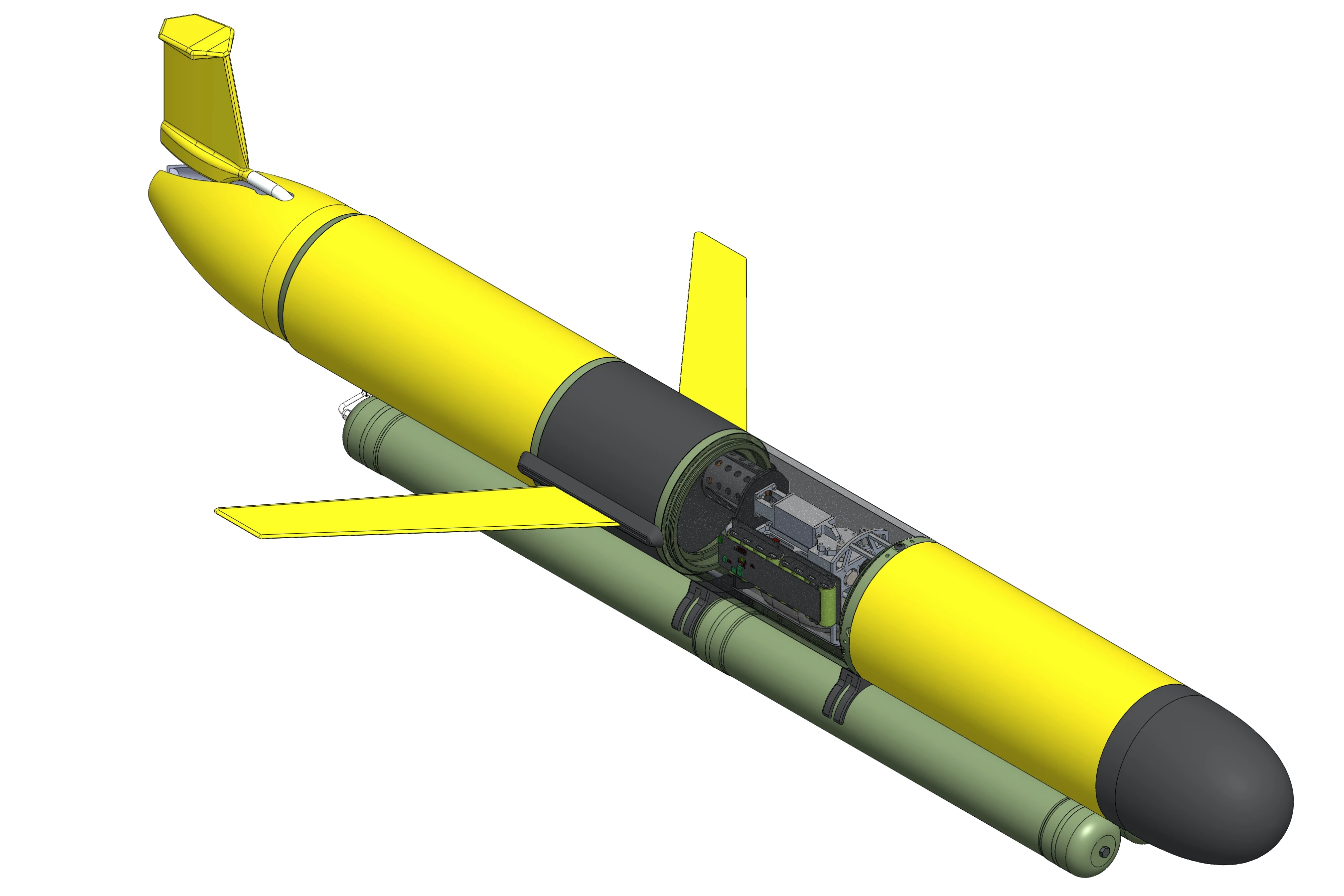

So first of all, just what are underwater gliders? Typically, they're torpedo-shaped autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) that propel themselves by varying their buoyancy. They alternate between sinking down and floating up, with their hydrofoil "wings" causing them to also glide forward while moving vertically through the water column.

They don't travel particularly quickly, but they also don't use much power. That said, they still do require some sort of an onboard power source, both for their buoyancy control mechanism and for their data-logging sensors. Batteries are usually used, but their capacity is limited, which thus limits the length and utility of glider missions.

That's where the Seatrec system comes in.

Based on a concept developed by oceanographer Henry Stommel, it's based around what are known as phase-change materials. These are substances that change states when heated or cooled, such as solids that become higher-volume liquids, or liquids that become higher-volume gases.

In the case of the sea glider setup, the material is a paraffin wax-based material, contained within an aluminum cylinder. Running length-wise through the center of that cylinder – surrounded by the wax – is a rubber tube filled with hydraulic oil.

When the vehicle is in the cool depths, the phase-change material takes the form of solid wax. As the glider rises and the water gets warmer, the material likewise heats up, melting and expanding into a liquid. The increased pressure within the cylinder squeezes on the tube, causing the oil within to be pushed out of the cylinder and through a linked generator.

As the high-pressure flowing oil spins up that generator, it creates electricity that can either be utilized right away, or stored in an onboard battery for later use. Once the glider makes its next dive, the wax cools and contracts back into a solid. This releases the pressure on the tube, allowing the oil to flow back into the cylinder. The process can thus be repeated over and over, with each rise and fall through the water.

In the present prototype form of the system, the wax melts when the water temperature reaches 10 ºC (50 ºF). By tweaking the formulation of the material, however, it's possible to raise or lower that figure for use in particularly hot or cold climates.

Of course, because the sea glider would begin its journey at the relatively warm surface of the ocean, it would require a little help coming up with the power for its first dive. This could be provided simply by charging its battery beforehand, essentially kickstarting the system so it could continue on its own.

Seatrec has already incorporated its technology into oceanographic floats, which rise and fall straight up and down at set geographical locations.

Company founder and CEO Dr. Yi Chao tells us that the new glider-specific system can be retrofitted onto existing AUVs, and will be the subject of sea trials conducted by New Jersey's Rutgers University in the second quarter of this year. Based on feedback from those trials, a commercial product should soon follow.

Source: Seatrec