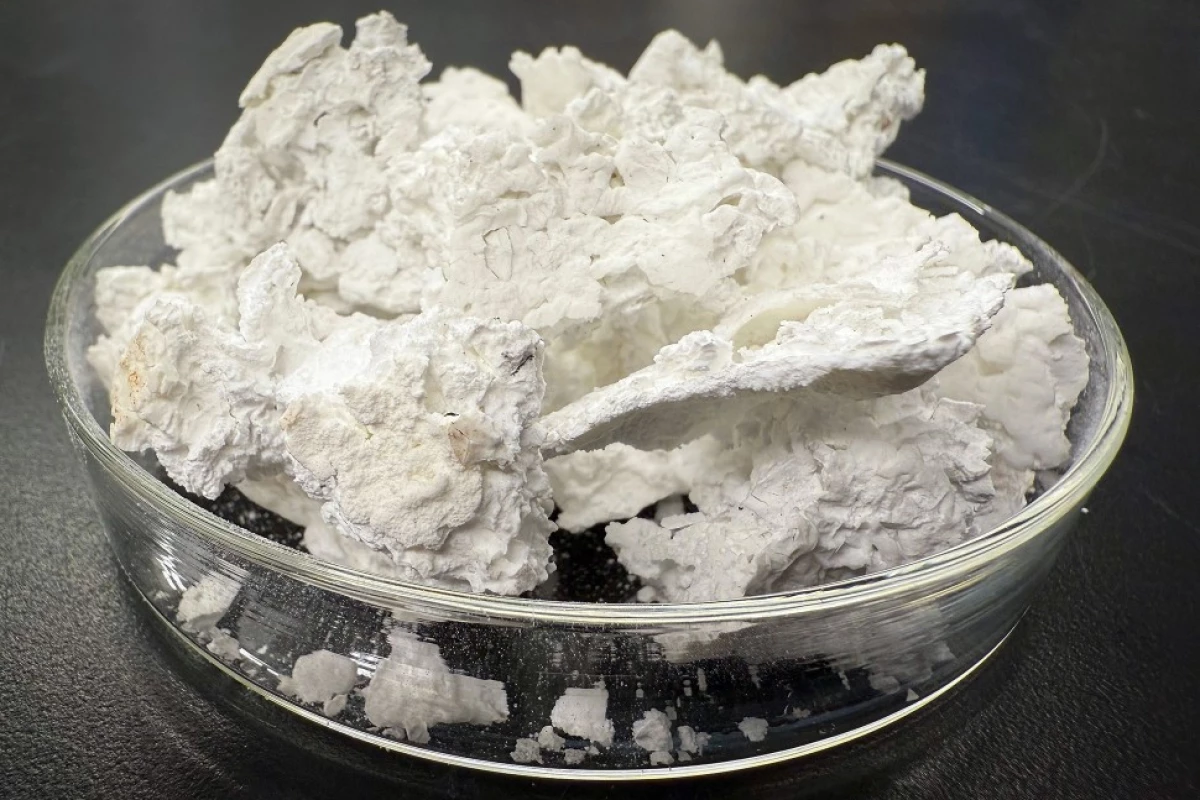

This strange white paste might not look like much, but it might help solve the sand shortage, while making the cement manufacturing process capture carbon dioxide instead of emitting it. Scientists at Northwestern University grew this stuff out of seawater, electricity and CO2.

Concrete is the most widely used artificial material on the planet – which is a shame, because making it also happens to be one of the most polluting processes. Worse still, at a global scale it requires huge amounts of sand, which is getting harder (financially and environmentally) to mine from coasts, seafloors and riverbeds.

An unassuming new material from Northwestern could help solve both problems. Composed of calcium carbonate and magnesium hydroxide in different ratios, it’s pretty simple to make – just take some seawater, zap it with electricity and bubble some CO2 through it.

The whole process is similar to how corals and mollusks build their shells, according to the team.

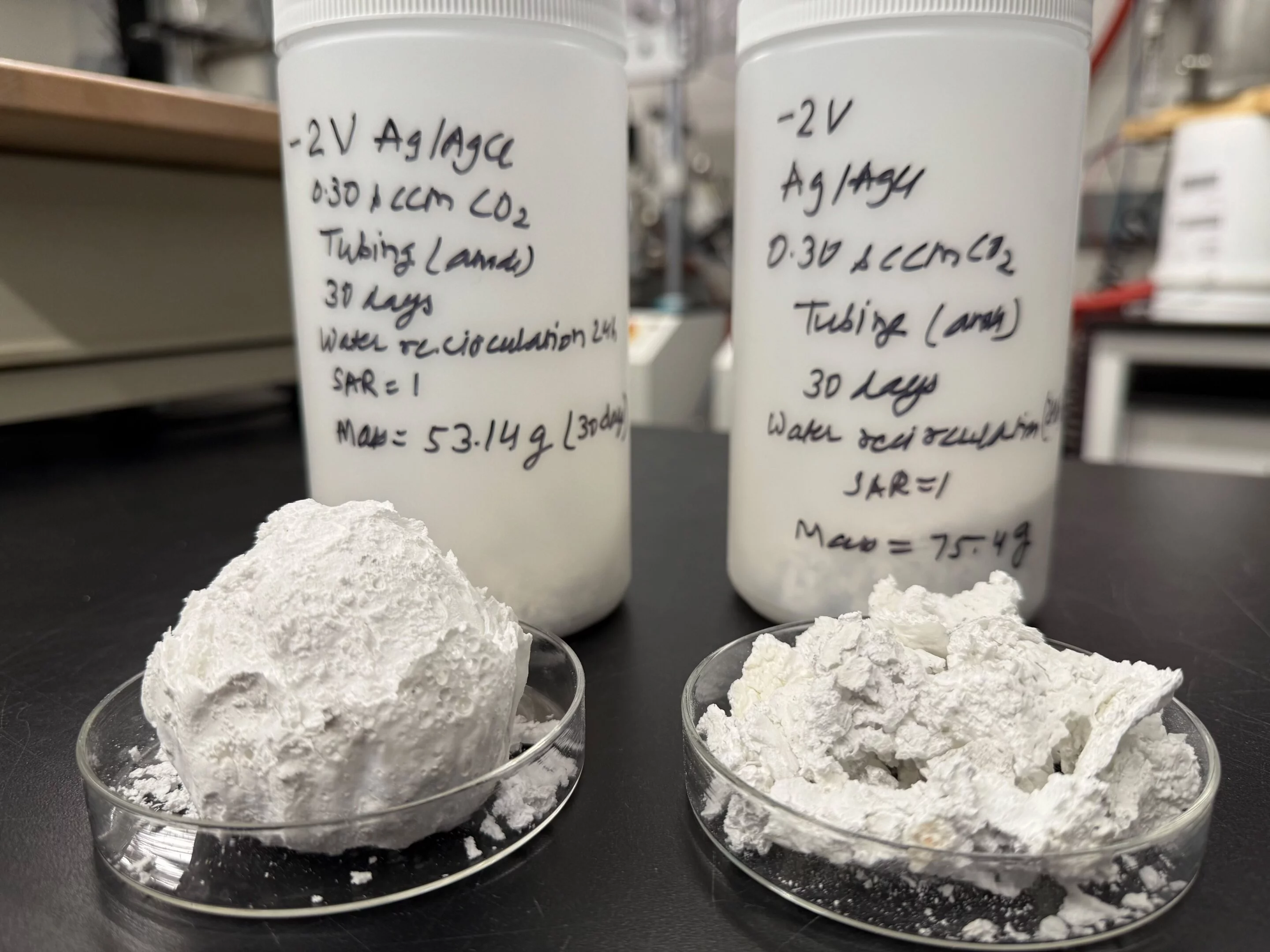

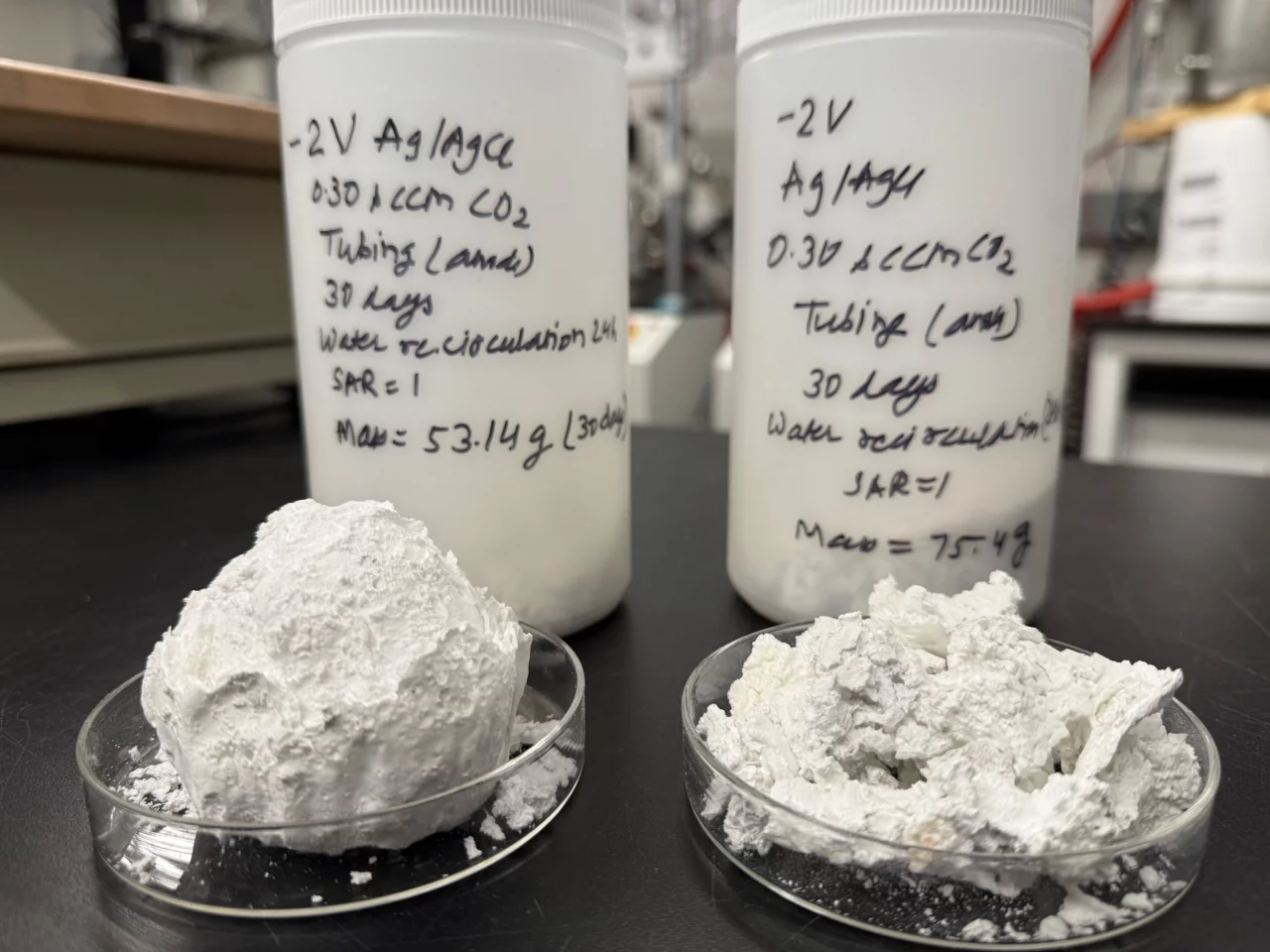

If you really want to get your thinking cap on, here's how they do it: two electrodes in the tank emit a low electrical current that splits the water molecules into hydrogen gas and hydroxide ions. When CO2 gas is added, the chemical composition of the water changes, increasing levels of bicarbonate ions. These hydroxide and bicarbonate ions react with other natural ions in seawater, producing solid minerals that gather at the electrodes.

The end result is a versatile white material that not only stores carbon, but can stand in for sand or gravel in cement, and also forms a foundational powder for other building materials like plaster and paint.

Intriguingly, the researchers found the material could be tweaked by adjusting the flow rate, timing and duration of the CO2 and seawater, and the voltage and current of the electricity.

“We showed that when we generate these materials, we can fully control their properties, such as the chemical composition, size, shape and porosity,” said Alessandro Rotta Loria, lead author of the study. “That gives us some flexibility to develop materials suited to different applications.”

This process is far greener than the usual method of making these building materials. Not only does it reduce the need to strip mine huge quantities of sand from the natural environment, but the only gaseous byproduct is hydrogen, which can itself be captured for use as clean fuel. The CO2 used to make the material could even come from emissions from regular cement production, in which case the process could make regular cement greener as a byproduct.

“We could create a circularity where we sequester CO2 right at the source,” Rotta Loria said. “And, if the concrete and cement plants are located on shorelines, we could use the ocean right next to them to feed dedicated reactors where CO2 is transformed through clean electricity into materials that can be used for myriad applications in the construction industry. Then, those materials would truly become carbon sinks.”

Seawater, electricity and carbon dioxide... These are not rare or expensive input items. Naturally, this process needs to prove itself at industrial scale, on commercial timelines, and survive the close scrutiny of the bean counters, but it sure looks to us like an innovation with impressive potential.

If this engineered carbon-capturing sand substitute proves cheaper than schlepping actual sand around at scale, it could make a meaningful contribution to decarbonization – but by itself, it won't produce entirely green cement. It's the next stage – where the sand is ground up with limestone and heated up north of 1,400°C (1,670 °K) in a kiln – that produces the lion's share of carbon emissions.

The research was published in the journal Advanced Sustainable Systems.

Source: Northwestern University